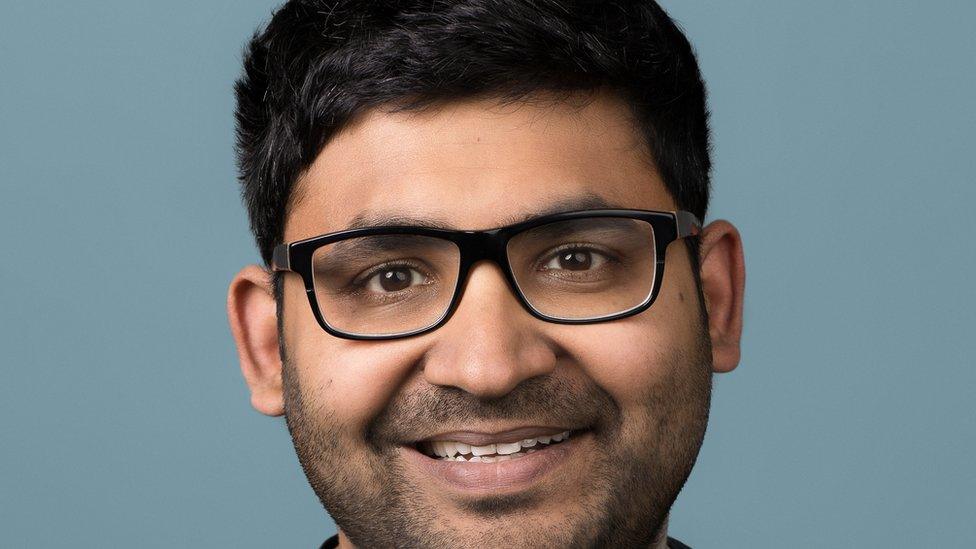

Parag Agrawal: Why Indian-born CEOs dominate Silicon Valley

- Published

Parag Agrawal succeeds Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey, who is stepping down

Parag Agrawal, who was appointed this week as Twitter's CEO, has joined at least a dozen other Indian-born techies in the corner offices of the world's most influential Silicon Valley companies.

Microsoft's Satya Nadella, Alphabet's Sundar Pichai, and the top bosses of IBM, Adobe, Palo Alto Networks, VMWare and Vimeo are all of Indian descent.

Indian-origin people account for just about 1% of the US population and 6% of Silicon Valley's workforce - and yet are disproportionately represented in the top brass. Why?

"No other nation in the world 'trains' so many citizens in such a gladiatorial manner as India does," says R Gopalakrishnan, former executive director of Tata Sons and co-author of The Made in India Manager.

"From birth certificates to death certificates, from school admissions to getting jobs, from infrastructural inadequacies to insufficient capacities," growing up in India equips Indians to be "natural managers," he adds, quoting the famous Indian corporate strategist C K Prahalad.

The competition and chaos, in other words, makes them adaptable problem-solvers - and, he adds, the fact that they often prioritise the professional over the personal helps in an American office culture of overwork.

"These are characteristics of top leaders anywhere in the world," Mr Gopalakrishnan says.

Indian-born Silicon Valley CEOs are also part of a four million-strong minority group that is among the wealthiest and most educated in the US.

About a million of them are scientists and engineers. More than 70% of H-1B visas - work permits for foreigners - issued by the US go to Indian software engineers, and 40% of all foreign-born engineers in cities like Seattle are from India.

"This is the result of a drastic shift in US immigration policy in the 1960s," write the authors of The Other One Percent: Indians in America.

Indian-born Satya Nadella was appointed Chairman of Microsoft this year, seven years after he became CEO

In the wake of the civil rights movement, national-origin quotas were replaced by those that gave preference to skills and family unification. Soon after, highly-educated Indians - scientists, engineers and doctors at first, and then, overwhelmingly, software programmers - began to arrive in the US.

This cohort of Indian immigrants did not "resemble any other immigrant group from any other nation", the authors say. They were "triply selected" - not only were they among the upper-caste privileged Indians who could afford to go to a reputed college, but they also belonged to a smaller sliver that could finance a masters in the US, which many of Silicon Valley's CEOs possess. And finally, the visa system further narrowed it down to those with specific skills - often in science, technology, engineering and maths or STEM as the preferred category is known - that meet the US's "high-end labour market needs".

"This is the cream of the crop and they are joining companies where the best rise to the top," says technology entrepreneur and academic Vivek Wadhwa. "The networks they have built [in Silicon Valley] have also given them an advantage - the idea was that they would help each other."

Mr Wadhwa adds that many of the India-born CEOs have also worked their way up the company ladder - and this, he believes, gives them a sense of humility that distinguishes them from many founder-CEOs who have been accused of being arrogant and entitled in their vision and management.

Mr Wadhwa says men like Mr Nadella and Mr Pichai also bring a certain amount of caution, reflection and a "gentler" culture that makes them ideal candidates for the top job - especially at a time when big tech's reputation has plummeted amid Congressional hearings, rows with foreign governments and the widening gulf between Silicon Valley's richest and the rest of America.

Their "low-key, non-abrasive leadership" is a huge plus, says Saritha Rai, who covers the tech industry in India for Bloomberg News.

India's diverse society, with so many customs and languages, "gives them [Indian-born managers] the ability to navigate complex situations, particularly when it comes to scaling organisations," says Indian-American billionaire businessman and venture capitalist Vinod Khosla, who co-founded Sun Microsystems.

"This plus a 'hard-work' ethic sets them up well," he adds.

There are more obvious reasons as well. The fact that so many Indians can speak English makes it easier for them to integrate into the diverse US tech industry. And Indian education's emphasis on math and science has created a thriving software industry, training graduates in the right skills, which are further buttressed in top engineering or management schools in the US.

"In other words, the success of Indian-born CEOs in America is as much about what's right with America - or at least what used to be right before immigration became more restricted after 9/11 - as what's right with India," economist Rupa Subramanya recently wrote in Foreign Policy magazine.

Sundar Pichai (R) was 43 when he was made CEO of Google in 2015

The huge backlog in the applications for US green cards, and increasing opportunities in the Indian market have certainly dimmed the allure of a career abroad.

"The American dream is getting replaced with the India-based start-up dream," Ms Rai says.

The recent emergence of India's "unicorns"- companies worth more than a $1bn - suggests that the country is starting to produce major tech companies, experts say. But, they add, it's too early to tell what global impact they will have.

"India's start-up ecosystem is relatively young. Role models of successful Indians both in entrepreneurship and in executive ranks have helped a lot but role models take time to spread," Mr Khosla says.

But most of the role models are still men - as are almost all of the Indian-born Silicon Valley CEOs. And their rapid rise is not enough reason to expect more diversity from the industry, experts say.

"Women's representation [in the tech industry] is nowhere close to what it should be," Ms Rai says.