Ukraine: The Indian girl who wouldn’t abandon her dog in a war zone

- Published

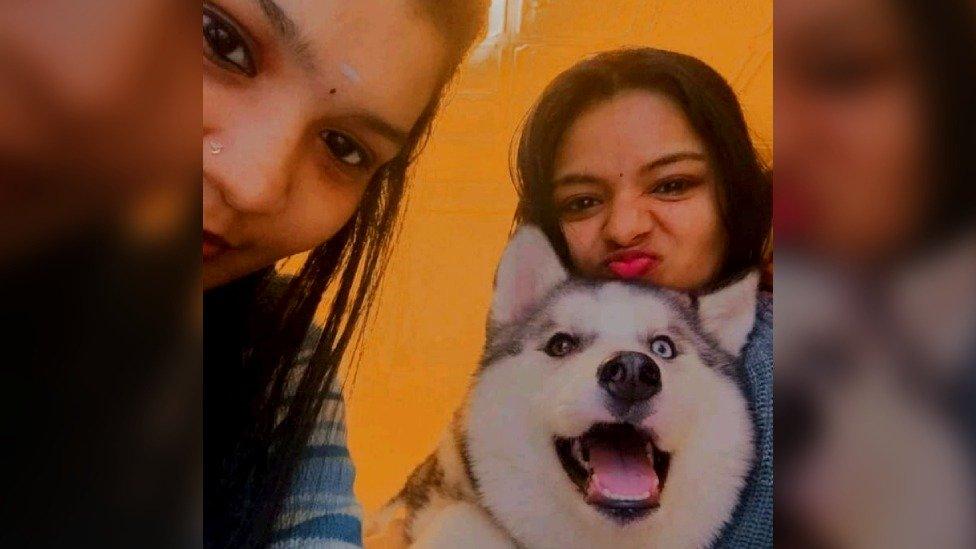

Arya Aldrin brought Zaira, a Siberian husky, from Ukraine to India

Is it selfish to bring your pet along when you are being evacuated from a war zone?

Arya Aldrin, a 20-year-old medical student who just fled Ukraine with her Siberian husky in tow, doesn't think so: "It would have been more selfish to leave my dog behind."

That's why she took five-month-old Zaira on a gruelling journey across thousands of kilometres to the southern Indian state of Kerala.

Many Indian students brought their cats and dogs back from Ukraine but Arya made headlines after a photo of her cradling Zaira - taken on a bus to the Romanian border - went viral.

The attention drew admirers and trolls - the latter asked if her parents sent her to Ukraine to study or to look after animals; others questioned why the Indian government should accommodate animals on evacuation flights when humans were in danger.

But Arya says Zaira didn't take up space meant for humans - she travelled in a cage in the cargo section of their flight from Romania to Delhi.

"I am a medical student - we are taught to save lives without discrimination. And it's not like leaving her behind would have helped anyone," she adds.

Many Indian students brought their cats and dogs back from Ukraine

Rescuing animals during a humanitarian crisis can be a thorny issue. In 2021, British national Pen Farthing, who ran an animal shelter in Afghanistan, was heavily criticised for leaving the country with the dogs and cats - but not his Afghan staff - after the Taliban took over.

He said that he couldn't take them along at the time due to threats from the Taliban. The shelter workers later made it to the UK.

For Arya and others like her, the stakes weren't as high. But the journey was nerve-wracking.

'I can't leave her'

Arya went to Ukraine in 2020 to study at the National Pirogov Memorial Medical University in Vinnytsya. She quickly made friends - many from her home state, Kerala - and liked living there.

A friend, who knew she loved animals, gifted a two-month-old puppy to her in December 2021. Arya named her Zaira after rejecting many "typical" options.

The two quickly bonded - when left alone at home while Arya attended classes, Zaira would refuse to eat, waiting eagerly for her human to return.

Arya, in turn, often turned down invites from friends so Zaira wouldn't be alone.

When rumblings of the war began, Arya says her only thought was, "whatever happens, I can't leave Zaira."

Well-meaning friends and relatives advised her to give the dog to someone temporarily, but Arya refused.

"I knew no-one else would love and pamper her like I would," she says.

When there was no choice but to evacuate, Arya's mother supported her decision to bring Zaira along. Her father disagreed at first but eventually came around.

Amid the crisis, she managed to get hold of a pet passport, vaccination papers and a microchip all in a day, helped by pet-friendly regulations and officials.

Arya got Zaira when she was two months old

Arya and Zaira, along with a friend, left Vinnytsya in a group on 26 February, two days after Russia invaded Ukraine.

The next day, they took a bus to the Romanian border. Zaira kept quiet and stuck close to Arya throughout, intimidated by noises and strangers.

The bus driver dropped them around 20km (12 miles) from the border because of the long queues of vehicles waiting to cross.

They began walking. Arya and her friend had packed juice and biscuits, as well as dog food for Zaira - they couldn't find bread or water in the shops.

On the way, Arya got her period and her back ached. Then Zaira began limping and seemed in distress.

Arya realised she would have to carry the dog.

"When I picked her up, she just rested on my shoulder like a baby," she recalls, although Zaira weighs about 16kg (35 pounds).

But the walk was excruciating - though others in the group helped, Arya often had to stop and rest her arms.

Along the way, she also discarded much of the food and juice to lighten the load - she estimates she must have carried Zaira for 10-12km.

By the time they reached the Romanian border, Arya only had dog food and travel documents in her bag.

A photo of Arya cradling Zaira on the bus to the Romanian border went viral

There, she waited amid a mass of anxious people for around seven hours.

There was a lot of pushing and shoving every time the gates opened. The one time Arya tried putting Zaira down, the dog got kicked and yelped in pain.

"I must have balanced on one leg for more than an hour. I just stood there hugging Zaira and cried, wishing we could go back to Vinnytsya even if it was dangerous," she says.

As they waited, Arya had to empty much of the dog food as well. The load, she says, felt unbearable.

When their turn finally came, Arya's friend managed to cross over but she and Zaira were shoved behind by a group of students.

Then, she held Zaira up, which caught an Ukrainian soldier's attention - and he allowed them to pass.

"I can't explain the sense of relief I felt when we crossed over," she says.

The journey to India

They were first taken to a shelter in Romania where they got food and water - kind-hearted volunteers also gave Arya a pair of second-hand shoes because hers were worn down.

They then waited hours to be taken to another shelter, closer to the Henri Coandă international airport in Bucharest. Here, Romanian police who took a liking to Zaira gave them more food and tissues, and helped them get a taxi to the airport.

A little before they boarded the evacuation flight arranged by the Indian government, Romanian authorities told Arya that Zaira would have to be put in a cage.

Arya (right) says Zaira is settling down well in India

It would take many more hours, a lot of running around - and another missed flight - before Arya and Zaira finally got on a plane to Delhi.

When she got some food on the flight, Arya says she ate a little and saved up the rest to feed Zaira when they landed.

Her journey to Kerala was delayed again because AirAsia, which was operating the flight from Delhi, didn't allow animals on board. So she took another flight.

By then, Arya's journey had made news, and a Kerala state minister had written a note on Facebook, external, praising her.

When she and Zaira reached Kochi airport the next day, she was greeted by a horde of journalists eager to interview her.

She first took Zaira to a vet for a check-up and a canine parvovirus vaccine and then - finally - made her way to her home in Munnar, a hill station.

There was concern that the Siberian husky - whose thick fur protects her from the harsh cold - would struggle in India's warm weather.

But Arya says Zaira seems to be settling down well. It also helps that Munnar is colder than most parts of Kerala - winter temperatures can drop to single digits.

"I'm actually feeling a little jealous now - Zaira seems to prefer spending time with my mother over me," Arya says, laughing.

You may also be interested in:

Watch: The musicians live-streaming music from a Kharkiv basement

Related topics

- Published7 March 2022

- Published3 March 2022