What a drone picking up blood samples tells about healthcare in India

- Published

Operators have used drones to test the delivery of medical supplies

Drones have been touted as a game-changer for India's medical industry, and for what it could do to make healthcare accessible to remote regions. Some operators have run successful test flights ever since India liberalised drone rules last year. The BBC's Andrew Clarance reports on what the future looks like.

Earlier this month, a drone carrying blood samples took off from Meerut, a city in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, and flew around 72km (44 miles) to Noida, a suburb of the India capital Delhi.

It took a little over an hour to reach, making a scheduled stop for a battery swap. By road, the journey would have taken more than two hours.

This trail run by a diagnostics lab using an unmanned aerial system is the first of many trials being held by drone manufacturers across the country who are testing deliveries for medical supplies, pathology samples and even blood units.

Skye Air Mobility, a drone logistics company, who built and flew the drone to Noida, say they have undertaken more than a 1,000 flights and delivered more than 3,500kg of mixed payload - ranging from e-commerce deliveries to blood samples - since November.

"Based on data we have gathered from the flights, we have significantly reduced the time it takes when using conventional means, by around 48%," Ankit Kumar, the CEO of Skye Air Mobility said.

The drone company also flew a trial in Gurgaon, a Delhi suburb, carrying a similar payload for one of India's biggest diagnostic companies, SRL Diagnostics. Samples were first collected by a lab specialist and then packed into a temperature-controlled carrier attached to the drone. It was then flown from a private hospital to a lab centre, where it was received by a lab specialist.

Police have used drones to surveil, and maintain law and order

All in all, it took about a third of the time it would have taken by road.

"This process", says Anand K, the CEO of SRL Diagnostics, "will help maximise sample processing abilities leading to an efficient lab operation, while benefiting patients who want faster delivery of vital results."

However public health experts say that there are only a few anecdotal experiences where trials have shown that drones can be used effectively in healthcare.

"The overall most important question is the cost- it is not yet effective simply because it is still in the trial phase. There is a lot more to be done," Rutuja Patil, a biotechnologist and public health researcher at the KEM Hospital Research Centre in the western city of Pune says.

Ms Patil led a public health project last year which used battery-powered drones to deliver essential medical items to community health centres in rural regions of the western state of Maharashtra.

"What we have shown right now is that there is a vehicle, software and automation, and that they can communicate together," she says, adding that the technology needs to scale up, for it to become cost effective.

She says flying vaccines or medicines which need to be transported and distributed between 2C and 8C, the so called cold chain - and in some cases even up to -20C - can become challenging.

In India, drones have been used to handle disaster relief and rescue operations. Uttar Pradesh has used them to monitor the Kumbh Mela, billed as the largest religious gathering on earth. They've also been used to transport Covid vaccines to far-flung villages in north-east India's mountainous regions, external.

Flying drone deliveries however was always not this easy. Drones were highly regulated, and private operators needed a lot of paperwork and licences to fly a delivery.

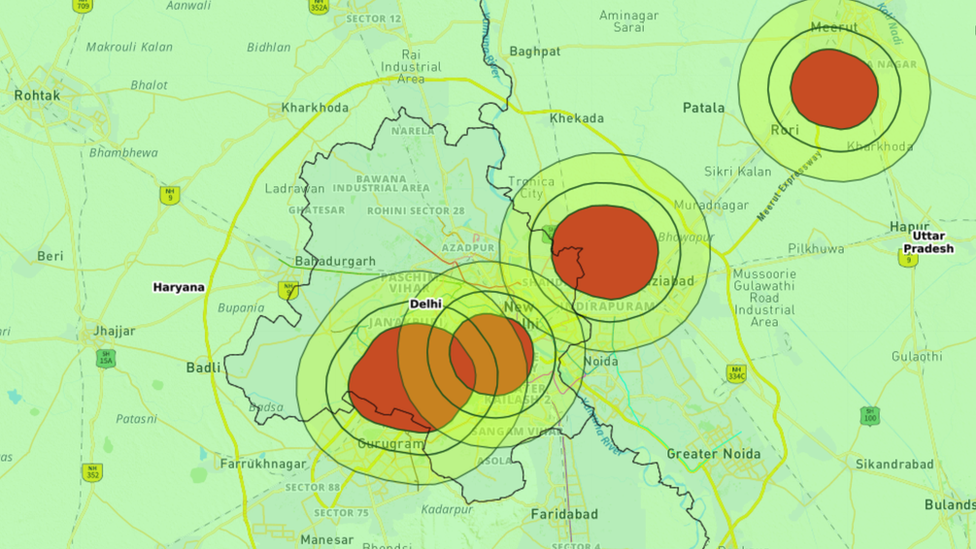

An airspace map shows the red zones and green zones over Delhi that shows regions where drones are allowed to fly

In August last year, the government liberalised rules and regulations, and slashed licences and fees that needed to be paid to operate commercial drones.

Under the new rules, paper work was reduced significantly, and the types of fees to be paid for running a drone operation was reduced from 72 to just four.

The government also rolled out an airspace map of the country divided into three zones, demarcated by colour - green, yellow and red - which informs drone operators of where they can fly and where they can't.

The most important change was that no permission was required for operating drones in green zones: a maximum height of 400ft from the sea level.

Licences were done away with for micro and nano drones. Nano drones are unmanned aerial systems weighing upto 250 grams, and micro drones weigh up to 2kg.

India's civil aviation ministry says that the drone services industry is expected to grow over 300 billion rupees ($3.9bn; £3.1bn), and generate over 10,000 direct jobs over the next three years.

For entrepreneurs like Mr Kumar, the future looks promising.

"By the end of this year, we will have more than a 100 drones deployed in more than 20 hubs which will be catering to different applications," he says.

You may also be interested in

The jungle-trekking Covid vaccinators helping to protect remote Indian villages.

- Published21 January 2022

- Published4 February 2022