Gyanvapi masjid: India dispute could become a religious flashpoint

- Published

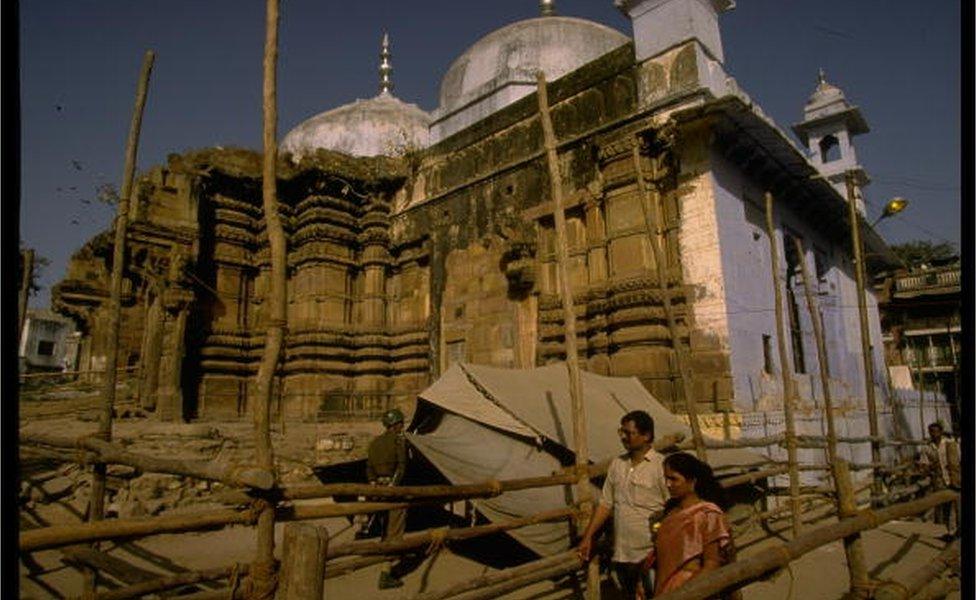

The golden top of the Vishwanath temple framed by the Gyanvapi mosque at the disputed site in Varanasi

In Varanasi, one of the world's oldest living cities, Hindus and Muslims have prayed close to each other in a temple and a mosque that sit cheek by jowl.

The heavily-guarded complex points to its uneasy history. The Gyanvapi mosque is built on the ruins of the Vishwanath temple, a grand 16th Century Hindu shrine. The temple was partially destroyed in 1669 on the orders of Aurangzeb, the sixth Mughal emperor.

Now the place is in the throes of a dispute which could stoke fresh tensions in Hindu-majority India, where Muslims are the largest religious minority.

A bunch of Hindu petitioners have gone to a local court asking for access to pray at a shrine behind the mosque and other places within the complex. A controversial court order which allowed video-recorded survey of the mosque is said to have revealed a stone shaft that is the symbol of the Hindu deity Shiva, a claim that has been disputed by the mosque authorities.

After this, a part of the mosque has been sealed by the court without giving the mosque authorities a chance to present their case. The dispute has now reached the Supreme Court, which said on Tuesday that the complex would be protected, and prayers will continue in the mosque.

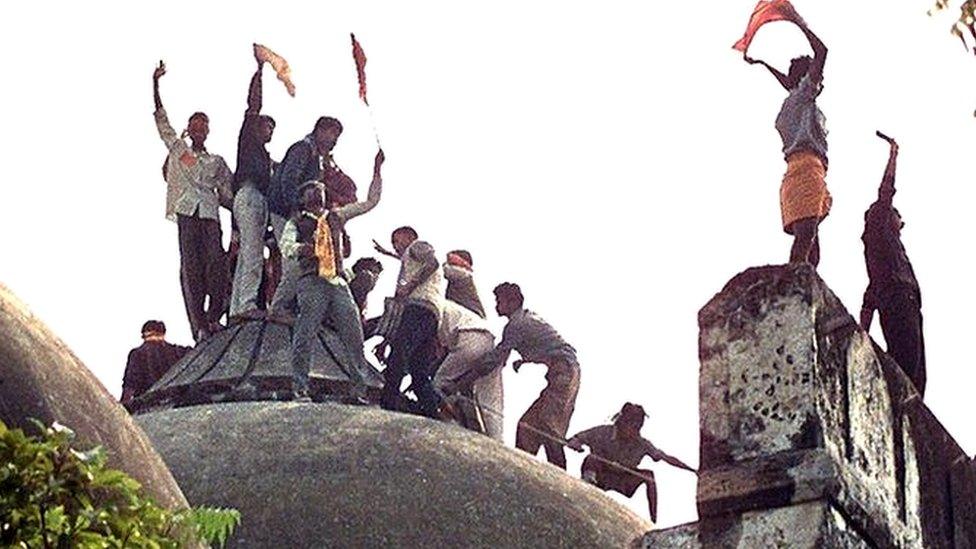

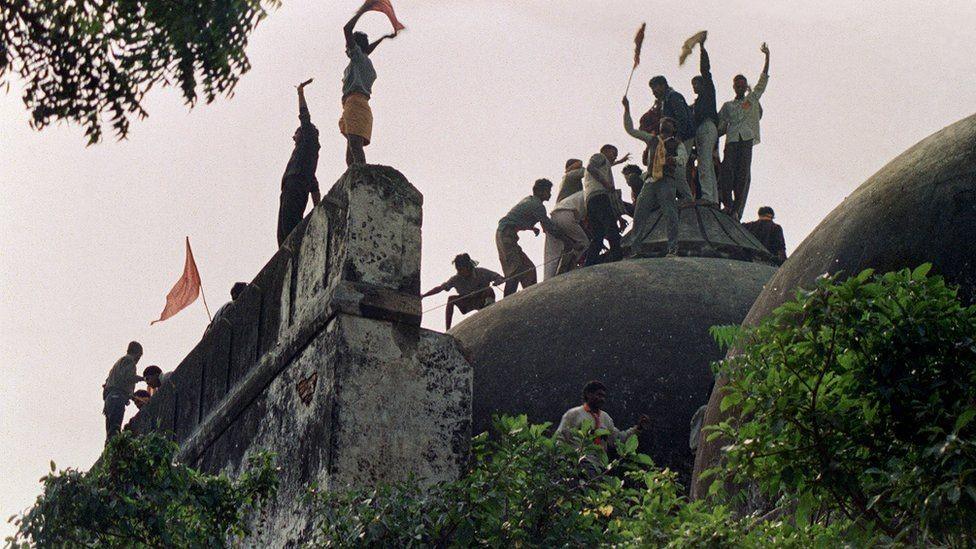

This has triggered fears of a re-run of a decades-long dispute involving the Babri Masjid, a 16th-Century mosque which was razed to the ground by Hindu mobs in the holy city of Ayodhya in 1992.

The Babri dispute reached a flashpoint in 1992 when a Hindu mob destroyed a mosque at the site

The demolition of the mosque climaxed a six-year-long campaign by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) - then in opposition - and sparked riots that killed nearly 2,000 people. In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled that the disputed site in Ayodhya should be given to Hindus who are now building a temple there. Muslims were given another plot to construct a mosque.

A 1991 law called the Places of Worship Act disallows conversion of a place of worship and maintains its religious character as "it existed" on 15 August 1947, India's Independence Day. Critics of the dispute in Varanasi say this is a defiance of the law. Asaduddin Owaisi, a prominent Muslim leader, says the "mosque exists and it will exist".

A leader of the ruling BJP in Uttar Pradesh state, where Varanasi is located, believes nothing is set in stone. "The truth has come to light... We will welcome and follow orders of the court in the matter," Keshav Prasad Maurya, the deputy chief minister, says.

It is not entirely clear what truth has to be uncovered.

For one, it is widely accepted that a temple existed at the site. The shrine was "grand in scale and execution, consisting of a central sanctum and surrounded by eight pavilions", according to Diana L Eck, a professor of comparative religion and Indian studies at Harvard University.

The site of the temple and mosque in Varanasi is heavily guarded

It is also established that in less than a century, the temple was "torn down at the command of Aurangzeb", Prof Eck says. "Half-dismantled, it became the foundation of the present Gyanvapi mosque".

It is also accepted that the mosque is built on the ruins of the temple. In Prof Eck's description "one wall of the old temple is still standing, set like a Hindu ornament in the matrix of the mosque".

"When viewed from the rear of the mosque, the dramatic contrast of the two traditions is evident: the ornate stone wall of the old temple, magnificent even in its ruined condition, topped by the simple white stucco dome of today's mosque".

The fact that a part of the ruined temple's wall was incorporated into the building "may have been a religiously clothed statement about the dire consequences of opposing Mughal authority", according to Audrey Truschke, author of Aurangzeb: The Man and the Myth.

Historians believe one reason why the temple was attacked by Aurangzeb was that its patrons were believed to have facilitated the escape from prison of Shivaji, a Hindu king who was a prominent enemy of the Mughals.

"Temples patronised by persons who had submitted to state authority but who subsequently became state enemies were often targeted by Mughal rulers," says Richard M Eaton, who teaches South Asian history at the University of Arizona.

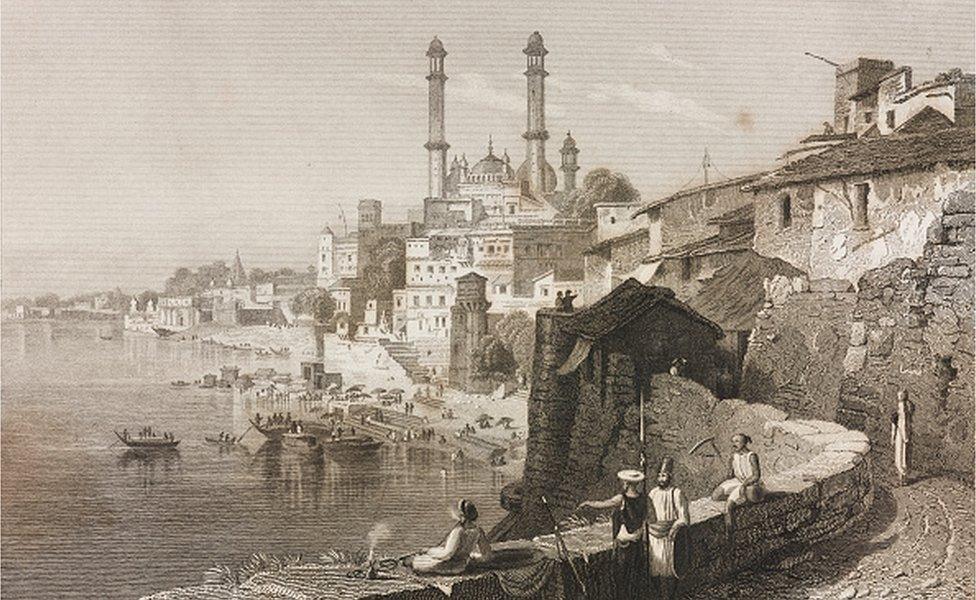

Varanasi is one of the world's oldest living cities

At least 14 temples were "certainly demolished" by Mughal officers during Aurangzeb's 49-year rule, according to Prof Eaton, who has recorded 80 examples of desecration of temples in India between the 12th and 18th Century.

"We shall never know the precise number of temples desecrated in Indian history," he says. However, what historians do know as fact is far from the exaggerated claims by the right-wing that up to 60,000 temples were demolished under Muslim rule.

In desecrating temples, Mughal rulers were following ancient Indian precedent, Prof Eaton says.

He adds that Muslim kings since the late 12th Century, and Hindu kings since at least the 7th Century "looted, redefined, or destroyed temples, patronised by enemy kings or state rebels as the normal means of detaching defeated rulers from the most prominent manifestations of their former sovereign authority, thereby rendering them politically impotent."

This is not exceptional, say historians. European history had its share of religious conflict and desecration of churches. Northern Europe, for example, saw many Catholic structures demolished or desecrated during the Protestant revolt in the 18th Century. Such examples include the desecration of Utrecht Cathedral in 1566, or the near-complete demolition of St Andrews Cathedral in Scotland in 1559.

A sketch of the Gyanvapi mosque in the 19th Century

But as Pratap Bhanu Mehta, a prominent commentator, observes: "Secularism will be deepened if it lets history be history, not make history the foundations of a secular ethic." And that the ongoing dispute in Varanasi can only end up opening "another communal front"., external

Such concerns are premature, says Swapan Dasgupta, a right-leaning columnist. "There is, as yet, no demand for the removal of the mosque and the restoration of the previously existing state of affairs… Also the law does not allow any scope for the present religious character of a shrine to be modified," he wrote. "To that extent, the present tussle in Varanasi is aimed at securing greater elbow room for worshippers, external."

Such assurances do not find many takers. Last year the Supreme Court accepted a petition challenging the Places of Worship law, which by itself could open a fresh fault line.

"This campaign [in Varanasi] is just the beginning of a series of demands in respect to other places of worship on which there are [Hindu] claims," says Madan Lokur, a retired justice of India's Supreme Court.

This could easily lead to a lifetime of strife.

- Published1 October 2020

- Published6 December 2017