NFHS-5: Indians are getting fatter - and it's a big problem

- Published

Indians are getting fatter, according to a new government survey, and experts are warning about a health emergency unless the growing obesity problem is tackled on a war footing.

Once considered a problem of the affluent West, obesity has been spreading in recent years in low and middle-income countries - and nowhere is it spreading more rapidly than in India.

Long known as a country of malnourished, underweight people, it has broken into the top five countries, external in terms of obesity in the past few years.

One estimate in 2016 put 135 million Indians as overweight or obese. That number, health experts say, has been growing rapidly and the country's undernourished population is being replaced by an overweight one.

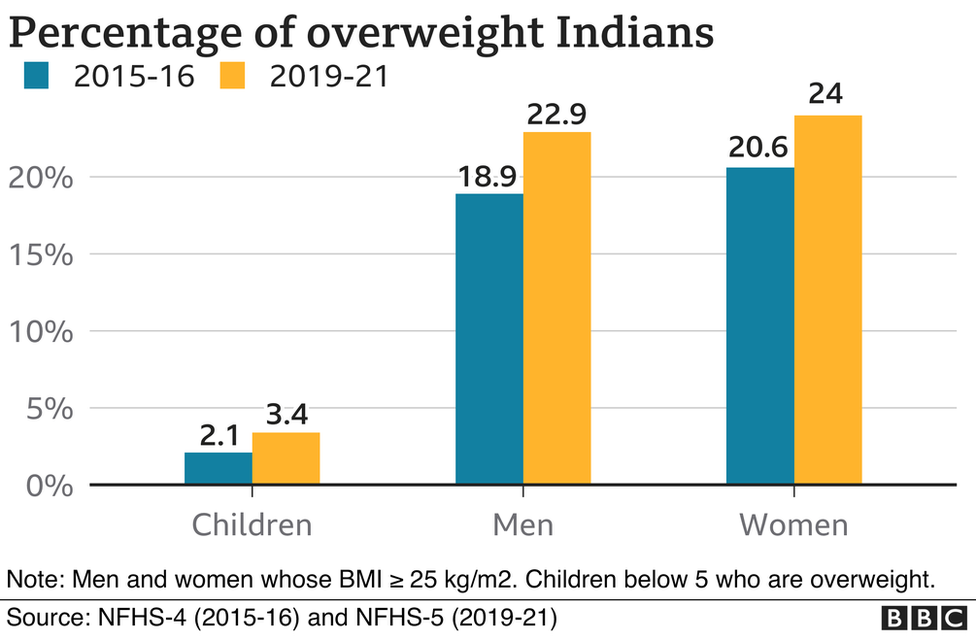

According to the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), the most comprehensive household survey of health and social indicators by the government, nearly 23% of men and 24% of women were found to have a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or more - a 4% increase for both genders over 2015-16. The data also shows that 3.4% of children under five are now overweight compared with 2.1% in 2015-16.

"We are in an obesity epidemic in India and globally, and I fear it could soon become a pandemic if we don't address it soon," warns Dr Ravindran Kumeran, a surgeon in the southern city of Chennai (Madras) and founder of the Obesity Foundation of India.

Dr Kumeran blames sedentary lifestyles and the easy availability of cheap, fattening foods as the main reasons why "most of us, particularly in urban India, are now out of shape".

BMI, which is calculated by taking an individual's height and weight into account, is the most accepted measure globally to classify people into "normal", "overweight", "obese" and "morbidly obese". According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a BMI of 25 or above is considered overweight.

But Dr Kumeran and many other health experts believe that for South Asian populations, it needs to be adjusted at least two points lower at each stage because we are prone to "central obesity", which means that we easily put on belly fat, and that's more unhealthy than weight anywhere else on the body. This would mean that an Indian with a BMI of 23 would be overweight.

"If you take 23 as the cut-off point for overweight, I think half the population of India - certainly the urban population - would be overweight," says Dr Kumeran.

According to WHO, too much body fat increases the risk of non-communicable diseases, including 13 types of cancer, type-2 diabetes, heart problems and lung conditions. And last year, obesity accounted for 2.8 million deaths, external globally.

Dr Pradeep Chowbey, former president of the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (Ifso), says "every 10kg of extra weight reduces life by three years. So, if someone is overweight by 50kg, they might end up losing 15 years of life. We also saw that mortality during Covid was three times higher for overweight and obese patients."

Dr Chowbey, who pioneered bariatric surgery in India 20 years ago - used as a last resort to treat dangerously obese people with a BMI of 40 or above - says obesity's medical impact is well known, but what is less talked about is its psychological and social impact.

"We did a survey of a 1,000 individuals three years back and we found that being overweight impacted sexual health, it led to poor self-image which could impact people's psyche and lead to marital disharmony."

And no-one knows it better than Siddharth Mukherjee, a 56-year-old actor who underwent bariatric surgery in 2015.

An athlete, he weighed 80-85kg until a few years ago when an accident put an end to his sporting career.

"But I had a sportsperson's diet. I ate a lot of oily, spicy food and I enjoyed drinking, so I kept putting on weight and it went up to 188kg," he said.

And with that came a host of illnesses - diabetes, high cholesterol levels, and thyroid problems - and during a holiday in 2014, he suddenly developed breathing difficulties.

Actor Siddharth Mukherjee (before and after his surgery) says to be fat is "a curse"

"I couldn't breathe lying down so I had to sleep sitting up," he said. "But Dr Chowbey has given me a new life. My weight is generally down to 96kg. I go riding my bike, I act on stage, I go on holidays.

"There was a time when I couldn't climb a set of stairs, now I can walk for 17 to 18km in a day, I can eat sweets, I can wear fashionable clothes now."

He said to be fat was a curse for him.

"The world is a beautiful place, and we have a commitment to our families so I would tell people to stop being selfish and take care of their health."

Dr Chowbey says for people like Mr Mukherjee, bariatric surgery can be life-saving, but the most important thing is to create awareness about the perils of putting on weight in the first place.

But his efforts to get the government to recognise obesity as a disease have remained unsuccessful.

"The government has been busy trying to control infectious diseases and their focus is on communicable diseases, they have very little resources for lifestyle diseases. But obesity is very difficult and expensive to manage, it puts a huge burden on the healthcare system."

A few years ago, there was talk of a "sin tax" which would raise prices of unhealthy foods and drinks to discourage their consumption, but health experts say it never happened because of pushback from companies that market them.

Dr Kumeran says that India must adopt the same strategy to discourage unhealthy eating as it did with smoking.

He adds that once smoking was allowed in public places, including in flights and offices, but it's banned now. The government has made it mandatory for TV soaps and films to carry disclaimers and all cigarette packets have pictorial warnings.

Dr Kumeran says such repeated warnings help in reinforcing the message and the same needs to be done for obesity.

Data interpretation and graphics by the BBC's Shadab Nazmi

Read more on India's family survey from the BBC:

- Published12 January 2016

- Published10 July 2018

- Published17 June 2021