Char Dham Yatra: Can India balance development and devotion in the Himalayas?

- Published

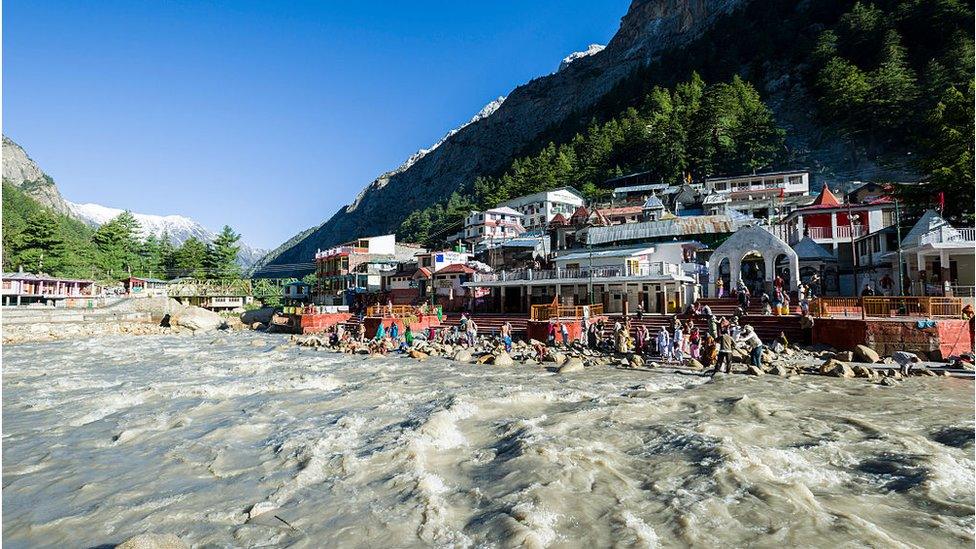

There are many revered pilgrimage sites in the Himalayan region

India's Himalayan region has a number of revered Hindu shrines and they attract millions of pilgrims every year. The region has witnessed several natural disasters over the years, killing thousands. Environmentalists say a balanced approach is needed to protect centuries-old traditions and also the Himalayas. The BBC's Sharanya Hrishikesh reports.

In 2021, while inaugurating a slew of projects, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that more tourists would visit the northern state of Uttarakhand over the next decade than in the past 100 years.

Much of this, he said, could be attributed to a major infrastructure push by the federal and state governments - both led by the Bharatiya Janata Party, which has a huge support base among India's majority Hindu community - to improve connectivity to famous pilgrimage spots in Uttarakhand.

The mountainous state, where several Himalayan peaks and glaciers are located, is home to some of the holiest sites for Hindus, including the temple towns of Kedarnath, Badrinath, Yamunotri and Gangotri which are part of the Himalayan Char Dham Yatra (Four Pilgrimages).

There are many other revered sites in the Himalayan region, including the Amarnath cave shrine and Vaishno Devi temple in Indian-administered Kashmir.

For centuries, the faithful have braved the biting cold and treacherous mountainous paths to pray at these shrines, some of which are only open for a few months in the year.

Hundreds of thousands of devotees undertake the Char Dham pilgrimage every year

But experts say that the surge in the number of worshippers over the past couple of decades - partly due to greater mobility and connectivity - and the infrastructural development to accommodate them are damaging the fragile ecological balance of the region, which is vulnerable to earthquakes and landslides.

A ban, they say, cannot be a solution when centuries-old traditions are involved, but there are several steps such as regulation that can be done without disrespecting religious sentiments.

"There is too much and too frequent intervention in these fragile regions. Earlier, villagers in remote areas would wait years to get access to one road. Now, there is a major expansion in facilities - but they don't cater as much to locals as they do to people from other states," says Kiran Shinde, a senior lecturer at La Trobe University in Australia who has worked extensively on religious tourism and urban planning.

While managing massive religious gatherings is always a tough task, India does have successful examples such as the Kumbh Mela, which is held across four states.

But the issues in vulnerable hilly areas are varied and manifold.

Several infrastructure initiatives in the region - including the ambitious Char Dham road-widening project - have been challenged by environmentalists and local residents on ecological grounds.

The Amarnath shrine is open only for a few months in a year

Ravi Chopra, a senior environmentalist who headed a committee formed by the Supreme Court to examine concerns about the Char Dham project, resigned in February, external. He wrote in a letter that he was "disappointed" by a top court order that ignored recommendations on the proposed road width made by a section of the panel.

"Sustainable development demands approaches that are both geologically and ecologically sound… As a member of the [committee], however, I saw at close quarters the desecration of the once impregnable Himalayas," he wrote.

There are other worries too.

A team of researchers, which studied a flash flood disaster that killed more than 200 people in Uttarakhand in February 2021, said in a report that rising temperatures were increasing the frequency of rock falls in the Himalayas, which could increase the danger to people.

Like most countries, India is also frequently facing extreme weather events, which some studies, external have partly attributed to climate change.

Earlier in July, at least 16 pilgrims were killed after flash floods hit their makeshift camps near the Amarnath shrine.

A top weather scientist told reporters, external that the floods may have been triggered by a cloudburst, which led to "highly intense and highly localised rainfall that our automatic weather station could not catch".

"We have no means of measuring the rainfall there as it is a very remote area," added Sonam Lotus, director of the Jammu and Kashmir meteorological department.

In 2013, the town of Kedarnath was hit by devastating floods - triggered by heavy monsoon rains - in which thousands of people were swept away. While the memory remains painful, it hasn't deterred pilgrims from visiting the shrine - this season, the turnout is expected to cross, external 2019's record of a million visitors, officials have said.

In 2013, a massive flood killed thousands of people and caused heavy damage in Kedarnath

To be sure, these tourists bring much-needed revenue to state governments - this can reduce the incentive to take tough calls.

Dr Shinde says that there is often an "institutional vacuum" when it comes to dealing with the fallout of religious tourism.

"While religious actors actively participate in promotion and management of the religious tourism economy at local levels, they hardly shoulder responsibilities of addressing the negative environmental impacts," he wrote in a 2018 paper, external.

While increased accessibility has allowed many more people across the country and even abroad to visit these sacred shrines, experts say the process needs a "fundamental rethink".

"The last-mile approach [to the shrine] should be made a little more difficult for pilgrims. Currently, not just the destination but even intermediate spots along the way are under too much pressure," says Sreedhar Ramamurthi, an environmentalist.

Authorities also need to talk to more stakeholders to develop better policies for environmentally fragile pilgrimage spots, Dr Shinde says.

"Most of the pilgrimage economy is informal, from the local priests who conduct religious ceremonies for devotees to the people who take pilgrims on ponies to the shrine. The latter would know the terrain and alternative routes better than most people," he says.

Most experts agree that regulating pilgrim numbers according to the terrain's capacity is essential.

In addition, awareness programmes can also make some difference, Dr Shinde adds.

"The right messaging is important. Authorities need to provide regular, updated information through advertisements and public service broadcasters that also highlight the risks and dangers involved in the journey," he says.

While there could be political risks in announcing restrictions on such a sensitive subject, Mr Modi - the most popular politician in the country - would most likely be able to pull it off, observers say.

You may be interested in:

Watch: Millions in India’s Assam state are struggling to piece together their lives after devastating floods