How ads sold soap and pills to women in colonial India

- Published

A 1933 advert for a tonic called Stri Mitra or A Woman's Friend featured a lipstick-wearing woman with her hair tied back

After joining the consumer goods giant Unilever in 1937, a young Indian manager took part in what was possibly the first major marketing survey in the country based on household interviews.

Female interviewers defied social conventions of the time by visiting the homes of strangers and asking middle-class housewives about which soap they preferred to use, recounted Prakash Tandon - who later became an influential business leader - in his biography.

The interviewers pressed on even after they received a familiar reply - "my husband chooses" - which hewed to the conventional thinking of the time that Indian men controlled what their families bought.

On further prodding, a respondent said: "Oh I see what you mean. My husband chooses, but of course, I tell him what to choose."

After this survey, Lever Brothers - the then Indian subsidiary of Unilever - began developing campaigns for their products targeting housewives.

This showed how a multinational firm "quickly applied its discovery of female centrality in decision-making [in India]", notes Douglas E Haynes, a professor of history at Dartmouth College.

Prof Haynes has researched the emergence of professional advertising in colonial India, especially during the interwar years. His new book, The Emergence of Brand-Name Capitalism in Late Colonial India, provides fascinating insights into how multinationals wooed Indian women and the middle class during the 1920s and 1930s, the early days of advertising in the subcontinent.

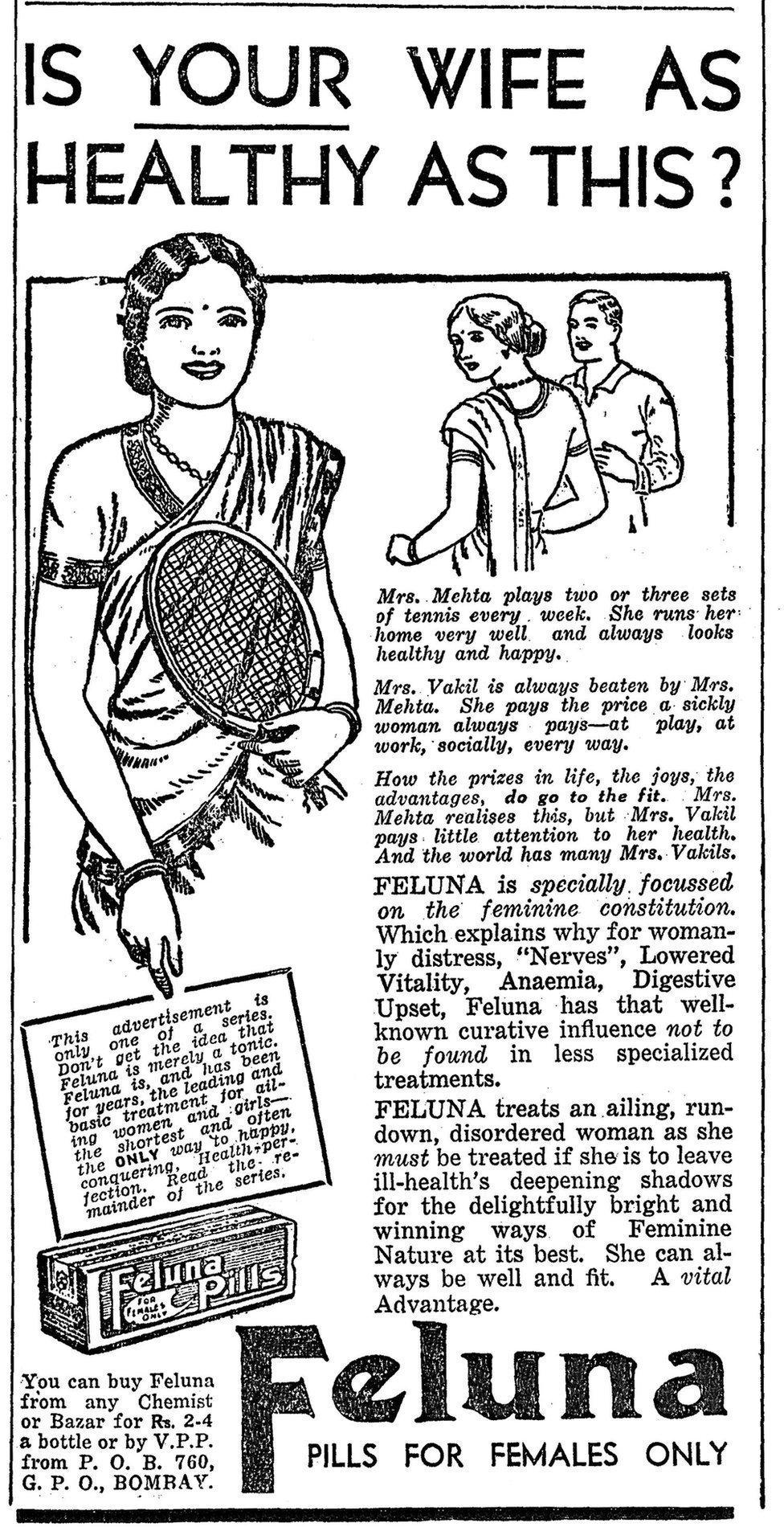

An advert for a health pill targeted at Indian women in September 1933

The firms gingerly tip-toed around local traditions to sell soaps, pills, perfumes and creams by promoting images of women which drew on ideals of marriage and motherhood. The firms also pitched products to husbands at a time when many housewives did not go to the market and stores for shopping, which was often done by men.

"The 1930s was a watershed in this respect, marking the dramatic advent of the female consumer [in India] in the multinationals' marketing efforts", says Prof Haynes.

The way a popular South Africa-made health pill for women called Feluna was launched in India offered an interesting example of how women were targeted.

The early adverts in Gujarati language newspapers featured images of European women touting the pill and addressing Indian husbands directly: Your wife - is she suffering? asked one advert. Husbands, guard the health of your wives, warned another.

The adverts talked about the "strains of motherhood" and urged the husband to "insist that she [their wife] takes a course of Feluna… let her have the health to be a mother in the real meaning of the word".

This 1923 advert of an Indian soap brand featured a female deity

Soon the adverts featured Indian women. One advert told the story of a Mrs Mehta, a sari-clad Indian woman. She carried a tennis racket and played "two or three sets of tennis a week".

Mrs Mehta was described as someone who always "looks healthy and happy". More importantly, she regularly defeated Mrs Vakil, another woman in the advert, who paid the price for being a "sickly woman" - at "play, at work, socially".

Not surprisingly, the advert carried a critical caveat about the sports-loving, modern Indian homemaker. "She runs her house very well," it pointedly said, dispelling any fears that her love for tennis came in the way of her familial duties.

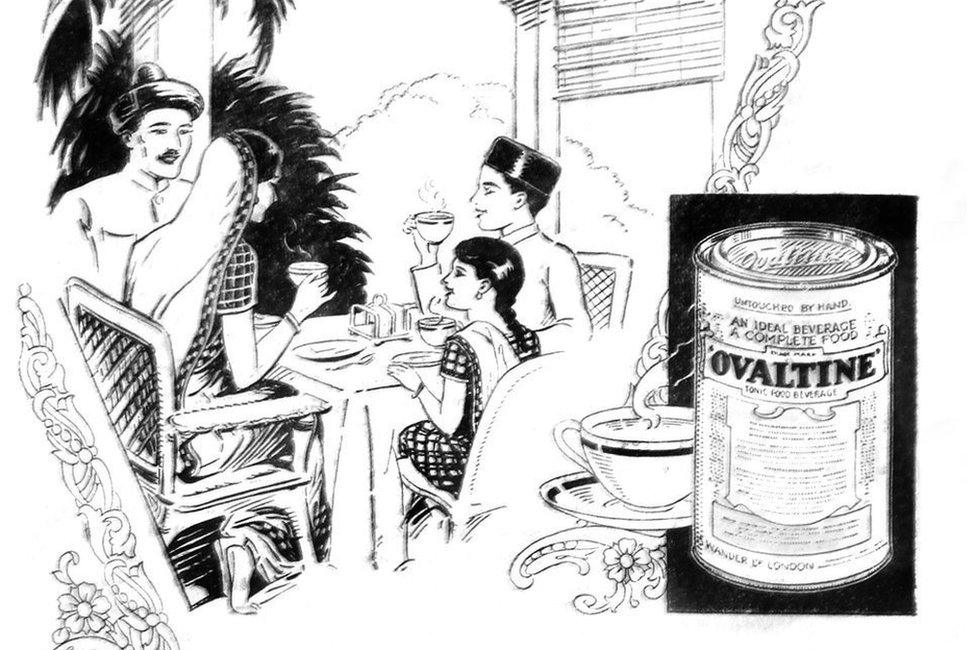

Some adverts appealed separately to expat, colonial housewives and Indian homemakers. Popular British malted health drink Ovaltine ran an advertising campaign - in English and vernacular papers, street hoardings, bus signs - that targeted "expat and elite Indians with European consumer values", according to Prof Haynes.

Ovaltine was sold as a "hot weather drink" to colonial housewives to cope with the Indian climate. In vernacular adverts targeting Indians, European-looking homes were replaced by Indian ones with simple furnishings, with families wearing Indian clothes and no house-helps in sight. The onus was on the housewife to provide "every member of [her] family with the necessary and pure nutrition".

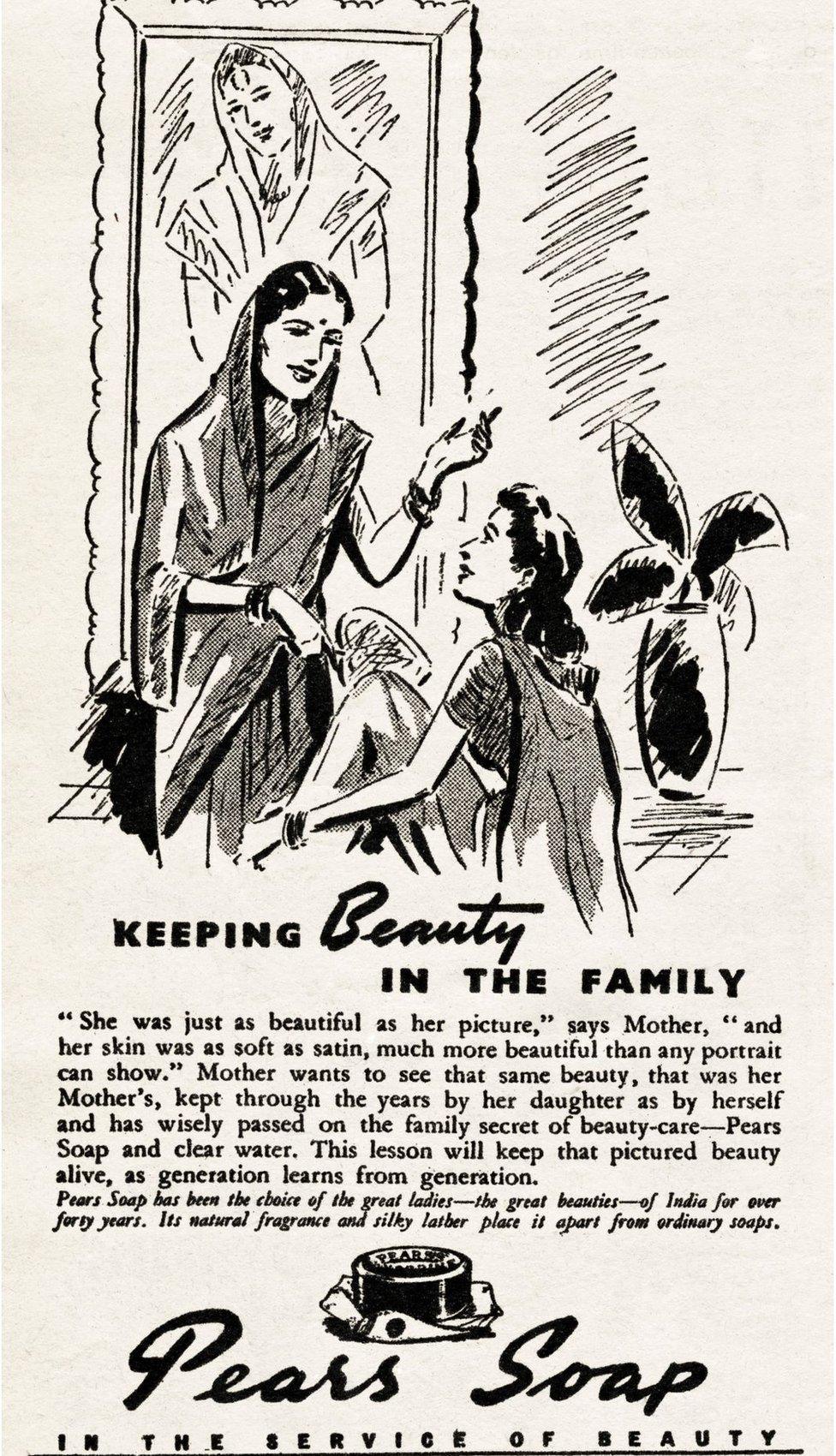

A Pears soap advert in India stresses family values

Beauty products were marketed a bit differently though: by the 1920s multinationals such as Ponds and Unilever were targeting Indian women with an ideal of beauty which was "contained and refashioned into what could be associated with an ideal of a married family", says Prof Haynes.

In popular campaigns beauty meant winning male attention, keeping the husband happy and - as one advert for a soap tellingly proclaimed - "social necessity", the idea that beautiful women got better matches and had to give lower dowry in the marriage market.

Most adverts talked about the importance of the skin "looking young" and being light-complexioned. Some openly appealed to the preferences for lighter skin - one cream promised to make "dark skin permanently fair".

They would typically feature short-haired young European modern girls or elegant, expensively dressed European women "conveying luxury and superior quality", according to Prof Haynes. Over the years, many firms signed up Bombay film actresses to promote their soaps.

"The commodification of beauty was a critical development of the 1920s and 1930s that has largely been ignored," says Prof Haynes.

A 1936 Ovaltine advert featured a middle-class Indian family

Clearly the housewife became the dominant female image in the adverts. But a more radical "modern girl", mimicking women who challenged gender stereotypes in the Bombay (now Mumbai) cinema, was slowly introduced as well, according to the academic.

An early advert trying to push the boundaries was for a tonic for women called Stri-Mitra (A Woman's Friend) - it showed a woman with her hair tied back and wearing lipstick, dressed in a sari and clearly marked as married with a bindi - a dot on the forehead that once was a symbol of a woman's marital status - and the mangalsutra, a necklace tied around a bride's neck.

Did the depiction of "modern" women in advertising provoke any social backlash? Prof Haynes says he found no such evidence.

Mahatma Gandhi baulked at both the consumer culture in advertising and the "modern girl".

"I have a fear that the modern girl loves to play Juliet to half a dozen Romeos. She loves adventure… dresses not to protect herself but to attract attention. She improves upon nature by painting herself and looking extraordinary," Gandhi wrote in 1939. But this didn't deter the firms wooing women consumers in colonial India.

Read more India stories from the BBC: