Gujarat results: Why Modi continues to be India’s biggest vote-getter

- Published

Mr Modi won three assembly elections on the trot and ruled Gujarat for more than 12 years

Incumbent politicians in India are among the most vulnerable in the world.

"Two out of three governments get thrown out in India. In America, the number is just the opposite - two out of the three get elected," Ruchir Sharma, a leading analyst, once noted.

Narendra Modi appears to be an exception. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader won three assembly elections on the trot and ruled Gujarat, his home state, for more than 12 years before moving to Delhi in 2014. He has since led his party to two decisive wins to rule India.

This has not stopped Prime Minister Modi from leading the campaign for the Gujarat state assembly. Thursday's record-breaking win - the BJP picked up 156 of the 182 seats and more than half of the popular vote - paved the way for a seventh-term in the state. It also proved that Mr Modi is "synonymous with Gujarat", as many commentators say.

Mr Modi characteristically made the Gujarat poll a referendum on himself. He spoke at more than 30 campaign meetings and undertook miles-long road shows to woo voters and grab saturation coverage on news networks. On the stump he invoked Gujarati asmita or pride and implored the voters to "trust" him and the BJP government. "You don't expect the prime minister to expend so much time and energy in a state election," says Amit Dholakia, a professor of political science at Gujarat's Maharaja Sayajirao University.

Mr Modi may have been made to work harder than usual. His ideology of strident Hindu nationalism, combined with promises of economic development, remains a big draw with voters. Religious riots convulsed Gujarat shortly after he first gained power in 2002, but that evidently did not dent his popularity. To be sure, Gujarat outpaces most of India in investment and per capita income; and boasts the country's fourth-largest economy.

Mr Modi retains a strong connect with the voters in Gujarat

However, as elsewhere in India, jobs are drying up and prices are rising here. Gujarat has lagged behind less richer states in health indicators like infant and maternal mortality rates. Mr Modi's successors in the local government have not enjoyed the same rapport with voters. In the 2017 state election, the party, facing a then-resurgent opposition Congress and a rebellion by supporters who belonged to an influential landowning community, scraped through with a narrow win.

"But once Mr Modi is on the ticket, the script changes," says Shekhar Gupta, editor-in-chief of ThePrint, an online news and current affairs site.

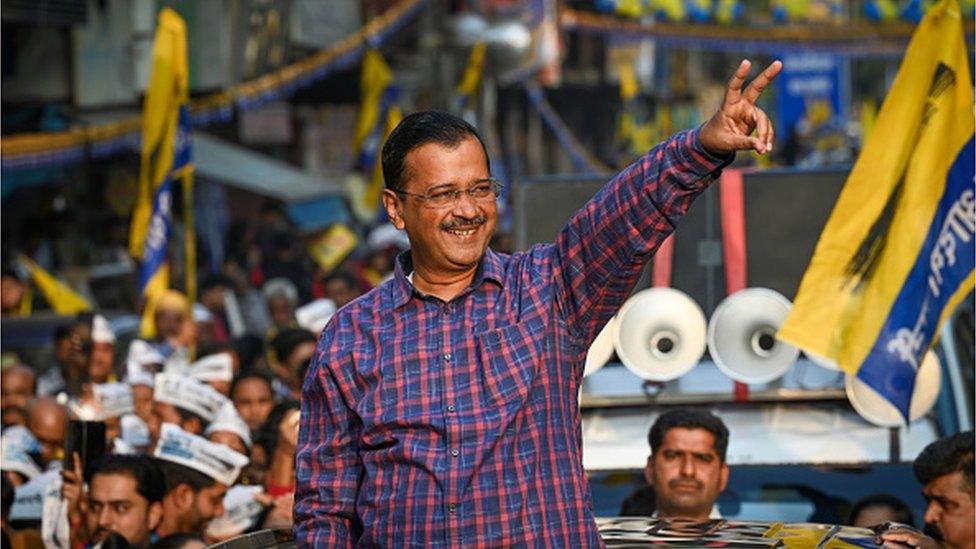

Mr Modi, say commentators, knows a setback for the BJP in Gujarat would hurt not only his party, but his own image. One reason he may have expended so much time and energy campaigning in the state this time could have to do with the arrival of the opposition Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), led by Arvind Kejriwal. The AAP has been ruling the city state of Delhi since 2015 and earlier this year won the key state of Punjab. On Wednesday, it wrested control of the cash-rich municipality of the capital, Delhi, which the BJP had ruled for 15 years.

Mr Kejriwal is a feisty leader who relishes throwing down the gauntlet to Mr Modi: he moved to Varanasi to contest against the BJP leader in the 2014 general elections. (He lost.) In Gujarat, his party debuted with a paltry five seats but picked up close to 13% of the popular vote, much of it at the expense of the main opposition Congress party. "It has built a space in the opposition. It needs to build a grassroots network and credible leaders," says Prof Dholakia.

Mr Kejriwal is a feisty leader who relishes throwing down the gauntlet to Mr Modi

A survey by YouGov, a global market research firm, and Delhi-based think tank Centre for Policy Research (CPR), in more than 200 cities and towns earlier this year found the AAP was gaining a foothold as a national alternative to the BJP, external, taking over the opposition space that Congress had enjoyed. "They've got a foot in the door. It doesn't mean that they are going to win the next election, but they become political contenders in the state," says Rahul Verma, a fellow with the Centre for Policy Research.

But Mr Modi's BJP remains a hard act to beat. His unquestionable appeal as a vote-getter is complemented by his party's Hindutva ideology, a powerful organisational apparatus, abundant resources, a record of governance, a strong social coalition and a largely supportive media.

Mr Modi is also helped in no small measure by a weak opposition - the Congress party's abject performance in Gujarat shows voters no longer find it appealing, say commentators. The party's narrow win over the BJP in the small mountain state of Himachal Pradesh - where voters have a reputation for kicking out incumbents - offers only a rare sliver of hope to an enfeebled party. However, the vote in Himachal Pradesh also "exemplified the limits of Mr Modi's formidable ability, external to singlehandedly push BJP through in state elections", according to Asim Ali, a political scientist.

What the BJP's sweeping win in Gujarat shows is that the rainbow coalition - upper, lower and middle-ranking castes, also called the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) - that the party has stitched together continues to fetch dividends. OBCs alone make up about half of Gujarat's more than 60 million people and now form a bulk of the party's voters.

Mr Modi's charisma and connect with voters remains the BJP's greatest strength. "But the party's greatest strength is also its greatest weakness. Take Mr Modi out of the equation, and the BJP looks vulnerable," says Prof Dholakia. "The dependence on Mr Modi is also an admission of the weakness of the local leadership. The other state leaders are not popular."

The BJP is now set to rule Gujarat without a break for 29 years - only the Communist Party of India (Marxist) ruled a state (West Bengal) for a longer time, a record 34 years. And Mr Modi, 72, continues to be a political outlier, defying anti-incumbency, both in his state and outside.

Read more India stories from the BBC: