UPSC: How Indians crack one of the world's toughest exams

- Published

Gamini Singla stood third in the civil service exam

For close to three years, Gamini Singla stayed away from friends, did not go on a vacation and avoided family meetings and celebrations.

She stopped bingeing on takeaways, going to the cinema and stepped away from social media. Instead, at her family home near the northern Indian city of Chandigarh, she woke up at the crack of dawn, pored over text books and studied for up to 10 hours a day. She crammed, did mock tests, watched YouTube videos of achievers and read newspapers and self-help books. Her parents and brother became her only companions. "Loneliness will be your companion. This loneliness allows you to grow," Ms Singla says.

She was preparing for the country's civil service exams, one of the toughest tests in the world. Rivalled possibly only by gaokao, China's national college-entrance exam, India's Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) exams funnel young men and women every year into the country's vast civil service.

A million candidates apply to appear in the gruelling three-stage exam every year. Less than 1% make it to the written test, the second stage. In 2021, when Ms Singla sat the exam, the success rate was the lowest in eight years. More than 1,800 made it to the interviews. Finally, 685 men and women qualified.

Ms Singla came third in the exam, along with two other women, external, a first in the history of the exam. She qualified to become a part of the elite IAS (Indian administrative service), which mostly runs the country through collectors of India's 766 districts, senior government officials and managers of state-owned companies. Successful candidates get to choose the state where they prefer to work.

"The day my results came in, I thought a weight had lifted. I went to the temple and then went dancing," the 24-year-old says.

In a country where good private jobs are limited and the state has an overwhelming presence in everyday life, the job of a civil servant is a coveted and powerful one, says Sanjay Srivastava, a sociologist at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. A government job also comes with an array of perks like loans, rental subsidies, travel and holidays at concessional rates.

Also, the civil service is of great attraction for people from small towns. "Joining the private sector might be easy enough, but moving up requires cultural capital. On the other hand, getting into [the] civil service is itself cultural capital," says Mr Srivastava.

Like most other aspirants, Ms Singla was an engineering graduate - a computer engineer who also interned with banking giant JP Morgan Chase. And like the others, she had her sights set on eventually becoming a bureaucrat. On a trip to the local government transport office to get her driving licence, she saw a bureaucrat there and sought an appointment with her, seeking her guidance. (She got it.) "The journey is so hard. It takes a long time, and the stakes are so high," she says.

Ms Singla's story of relentless endurance and monkish sacrifice at an age when many don't have a clue about what to do with their lives offers a glimpse into India's brutal exam system: endless cramming, involvement of the family, finding ways to save time and avoiding any distraction and a near-total withdrawal from the world. "There are moments of frustration and tiredness. It's mentally very tiring," she says.

Ms Singla studied up to 10 hours a day for the exam

Ms Singla followed what seemed like a marathon training plan. To take care of her health and last the distance, she moved to a diet of fruits, salads, dry fruits and porridge. To make sure no time was wasted, she would jump "200-300 times" in her room after every three hours at the study table instead of stepping out for exercise.

Free time needed to be used wisely so she read self-help books. She took scores of mock tests online to test her abilities. How do you, for example, answer 100 questions in a general knowledge objective test in two hours? "When I listened to videos of [previous] toppers, I realised everyone actually knows answers to 35-40 questions, and the rest is calculated guesswork," says Ms Singla.

Since one of the key exams is held in the winter, she would try to step "outside my comfort zone and experience a cold and disagreeable environment" by choosing the "coldest room with the least sunlight" for mock tests. She tried out three different jackets and chose the one that felt most comfortable. "I had heard of aspirants discussing their inability to write in their ill-suited, heavyweight jackets. So it is all worth it," says Ms Singla. "You are just giving it your best in every way."

The marathon also became a shared experience with her family. Ms Singla's parents, both government doctors, joined in enthusiastically. Her father, she says, read at least three newspapers daily - "newspapers make up 80% of your preparations for the exams" - and marked the important news to speed up his daughter's current affairs knowledge. Her brother helped with the mock tests. Her grandparents simply prayed for her success.

No effort was spared to make sure that Ms Singla was undisturbed. When construction work on two buildings opposite her home created a racket and blocked sunlight, her family demolished a room on their terrace to create a quieter and better lit place for her to study. To shield her from inquisitive relatives who wondered why their daughter was missing at family functions, her parents "stopped socialising and avoided family gatherings so I did not feel left out or isolated".

"They are part of my journey. They trod the same path. It's [the exam] a family effort," says Ms Singla.

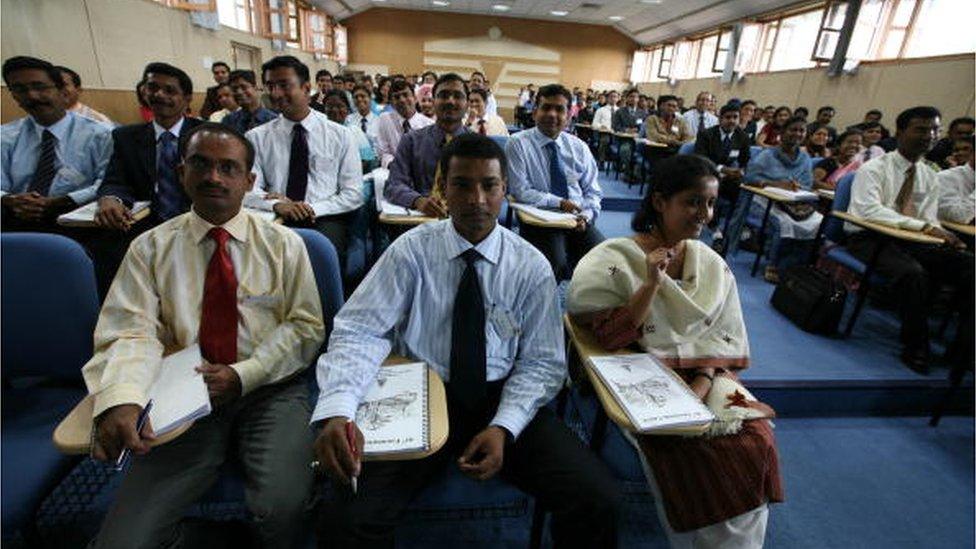

The exams funnel young men and women every year into India's vast civil service

Ms Singla belongs to India's privileged middle class who face fewer obstacles to their dreams of joining the bureaucracy. But the exams have also created a path of upward mobility for students from deprived backgrounds. Their families sell land and jewellery to send their children to coaching schools in big cities, says Frank Rausan Pereira, who produced a popular current affairs show on state-run TV, which became a hit with civil service aspirants.

Mr Pereira says most of today's aspirants come from India's teeming small towns and villages. He spoke of a young civil servant who was the son of a manual scavenger - someone who cleans human and animal waste from buckets or pits; it's a job performed mostly by members of low-caste communities - and who studied at home, cracked the exam and joined the prestigious foreign (diplomatic) service.

"I know aspirants who have prepared for 16 years after failing to crack the exam more than a dozen times in as many years," says Mr Pereira. (Aspirants have six attempts until the age of 32 - some underprivileged caste groups can sit the exams as many times as they want. Aspirants can first take the exam on turning 21.)

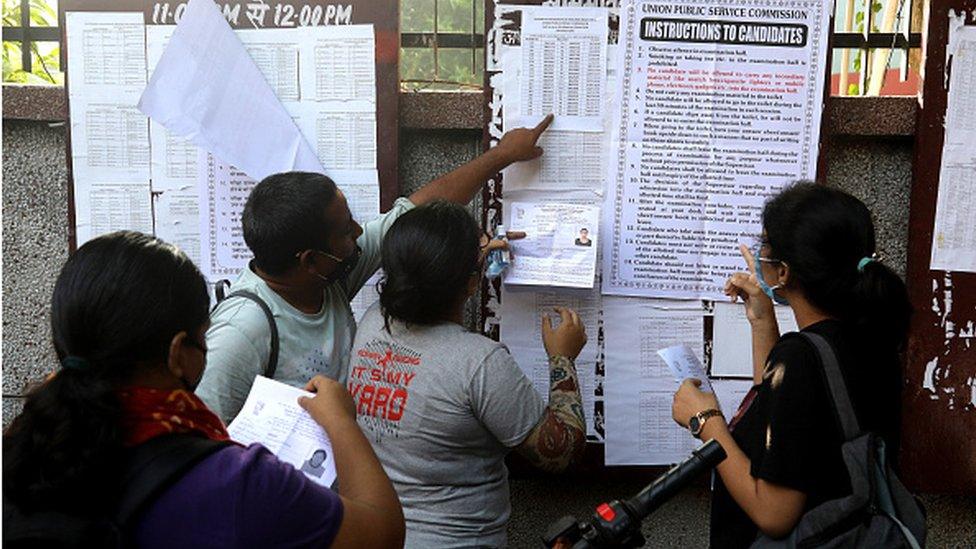

A million candidates apply to appear in the gruelling three-stage exam every year

Ms Singla says becoming a civil servant gives her a "great opportunity to make a true difference and impact many lives" in a vast and complex country. She has written a book on what it takes to "crack the world's toughest exam". It has chapters on 'How to make sacrifices', and 'Dealing with tragedies beyond your control' and 'Handling the pressure from your family', among other things.

Ms Singla told me she sometimes thinks she's "forgotten how to relax". She's enjoying the training and travelling around the country to prepare for her first assignment in the districts. "Life will become hectic," she says. "And it will become difficult to relax again."

Read more India stories from the BBC: