Gautam Adani: Will tycoon’s wealth woes hit India’s green energy dreams?

- Published

The Adani Group plans to spend $70bn in green energy and become a global renewable player by 2030

Two years ago, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced ambitious plans to make India a green energy colossus.

He pledged cutting emissions to net zero or becoming carbon neutral, meaning not adding to the amount of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere by 2070. (Although its demand for power and emissions are lower than Western countries', India is the world's third largest emitter of greenhouse gasses.) Mr Modi also promised for India to get half of its energy from renewable resources by 2030, and by the same year to slash projected carbon emissions by a billion tonnes.

One businessman who's key to Mr Modi's green energy plans is Gautam Adani, one of Asia's richest men who runs a sprawling port-to-energy conglomerate with seven publicly traded companies, including a renewable energy firm called Adani Green Energy. Mr Adani plans to spend $70bn (£58bn) in green energy and become a global renewable player by 2030. This money is expected to be spent on hybrid renewable power generation, making batteries and solar panels and using wind energy and green hydrogen.

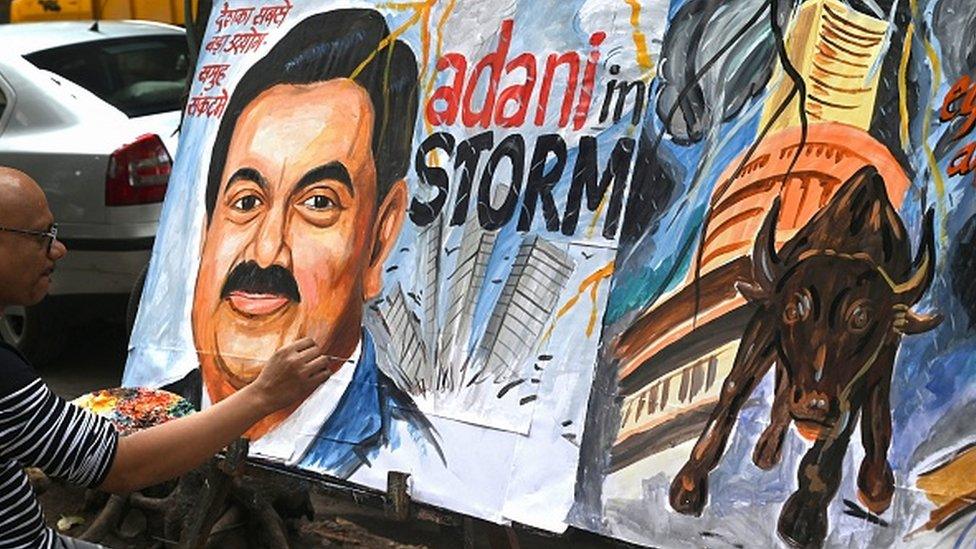

But Mr Adani's recent troubles have raised concerns about whether this means a setback for India's soaring energy ambitions. The listed companies in his group have seen some $120bn wiped off their market value after the US-based investment firm Hindenburg Research published a report accusing it of decades of "brazen" stock manipulation and accounting fraud. The group has dismissed the allegations as malicious and untrue, calling them an "attack on India".

The Adani Group has denied allegations of financial fraud

In the first sign of investors getting skittish, TotalEnergies, a French oil and gas group, put on pause a planned $4bn investment, external in a green hydrogen project with the Adani Group until there was more "clarity" on the situation. (Total has already invested more than $3bn in energy projects with the group). To calm investors, the group has said that its companies faced no "material refinancing risk or near-term liquidity issues". A spokesperson of the Adani Group told the BBC: "We do not anticipate change in energy transition plans of [the] Adani portfolio".

Experts believe it is too early to determine the impact of recent developments on India's climate plans. "The Adani group is a big player in the green energy space. Some of the fresh investments may be delayed. If they are not able to raise more financing, it will have some impact on green energy investments that it had originally planned," says Vibhuti Garg of the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. "But the momentum in renewable energy will continue."

In the coming decades, India's energy transition will be the biggest in the world. With 1.4 billion people, the country still needs to hook up large swathes of population and the last holdouts with power. India adds a city the size of London to its urban population every year. Industrial activity is increasing. There are more extreme weather events like heatwaves. A push towards electrical vehicles will further exacerbate demand for power.

Not surprisingly, the electricity regulator reckons that demand is expected to double in the next five years. India is the world's second-largest producer and consumer of coal. Three-quarters of the electricity produced uses coal and India is still building thermal plants. Yet the plan is that most of the additional capacity will come from renewable sources. And to reach net zero emissions by 2070, India needs $160bn every year between now and 2030, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). That's three times today's level of investment.

Three-quarters of the electricity produced in India uses coal

Apart from the Adani Group, the other big player in green energy are the Ambanis. Mukesh Ambani of Reliance Group, India's biggest firm, plans to spend $80bn on renewable power projects, external in the western state of Gujarat. Energy giant Tata Group is also revving up its clean energy play. Yet experts say India's insatiable energy demand requires many more players.

"If we need to meet so much of energy demand, we need many more private players, a few big and many small," says Ashwini K Swain of Centre for Policy Research, a Delhi-based think tank. He believes the the numbers of domestic green energy players has to grow. "We cannot work with half a dozen players and a couple of players who are disproportionately big," he says.

That's why the Adani Group's troubles could actually be an opportunity for other renewable energy players, says Tim Buckley of Australia-based Climate Energy Finance. He says he sees "huge potential capacity for other national players to "step up, leveraging their domestic skills and capacity, combined with expanding global capital access and interest in investing in Indian renewables and grid infrastructure".

India's total generation capacity of clean and dirty energy is 400 GW - and it plans add 500 GW in clean energy alone by 2030. It is an audacious ambition. A transition of this scale in a country which has depended on coal and oil so far to meet its energy demands is not going to be easy.

Mr Swain believes India should stop expanding coal capacity, and instead move to meeting some of its new demand from cleaner sources. For example, a fifth of India's electricity demand comes from irrigating its vast farms; powering the farms during daytime with solar energy could make everybody happy. "India's progress on renewable energy has been remarkable. There may be some delays and slowdowns, but those should not hamper the renewable energy growth," says Ms Garg.

Read more India stories from the BBC: