Kapil Sharma in Zwigato: When India's top comedian became a food delivery boy

- Published

The Zomato, Swiggy riders risking their lives to deliver food

In Zwigato, a new film, India's best-known comedian Kapil Sharma spends a lot of time weaving in and out of traffic on his bike, trying to deliver enough food orders that will earn him a bonus at the end of the day.

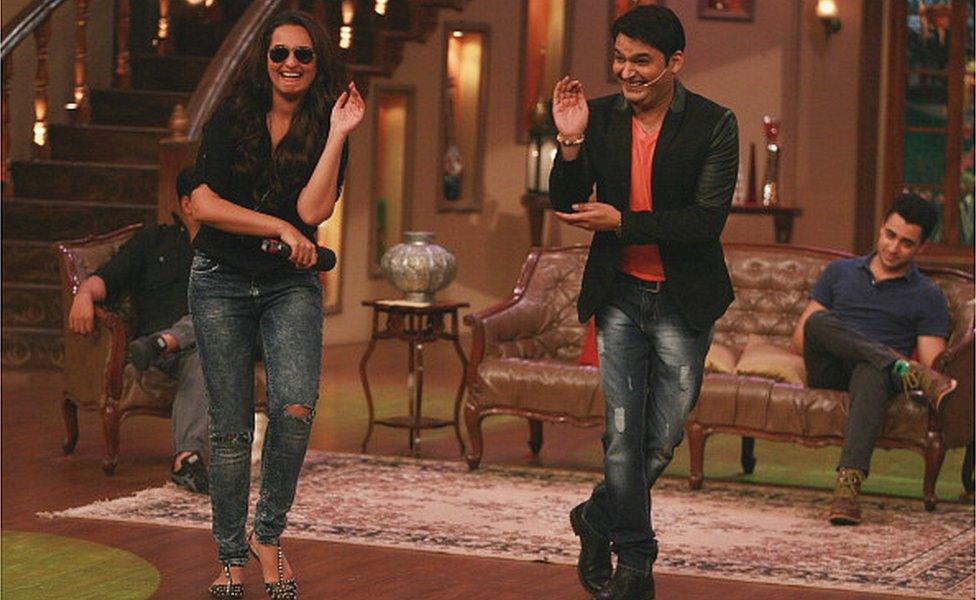

A struggling food delivery rider is an unlikely makeover for Sharma, the rambunctious host of a wildly popular comedy show. Supported by a slapstick comedy ensemble, Sharma makes fun of everyone - including the audience and celebrity guests - with an amiable swagger. He delivers punch lines and jokes - sometimes mildly bawdy and obviously sexist - in rapid-fire Hindi. He's often described as a "people's star".

But in Zwigato, directed by Nandita Das, Sharma plays Manas, a gloomy food delivery rider. He glides through a small city, wearing a stoic expression on his face and a cargo of food on his back. He cannot entirely make sense of the food delivery app on the phone mounted on his handlebar and its algorithms that are central to his livelihood. (In one scene his school-going son tells his puzzled father that he can also rate his customers.)

Back home - a two-room shanty - in a small city where he lives with his wife, Pratima (Shahana Goswami), two children and a bed-ridden mother, life swings between the anxiety of a precarious present and the promise of a better future. A nagging worry appears to devour Manas: can he deliver enough food to pick up good ratings, tips and bonuses to earn a living wage and secure his family?

Zwigato: New film starring Kapil Sharma tells the story of India's food delivery boys.

Manas and his mates appear, at once, to be ubiquitous and invisible - they are like a silent swarm of India's booming gig economy, run by a host of unicorn apps.

They whiz in and out of eateries and homes, picking and delivering orders. They throng outside noisy restaurant kitchens. They take high-rise elevators meant for the "service" staff, a euphemism for the menial help in India's punishing caste and class hierarchy. They take selfies with kind clients to get more ratings. They risk accidents and on-the-job injuries chasing time-bound deliveries on chaotic roads.

"They are like urban daily wage workers with fancy names like delivery riders or partners," Das told me. In one telling scene, Manas tells his manager, "You call us partners, but you are the ones who make the money."

At home, Manas, a loving husband and a doting father, is uncomfortable about Pratima taking up a job as a cleaner in a mall to boost family earnings. In the kitchen Pratima keeps a separate fraying tumbler to give drinking water to the trash picker. "The film is not only about trying to decode the world of algorithms and ratings. It's also about four days in the life of a family. And the context is filled with disparities of gender, caste and religion and our prejudices," says Das. The film is also about "common people, who, have become invisible in our popular cinema and stories".

Sharma is India's best-known comedian with a hugely successful show

But Zwigato's most compelling feature is its unsentimental, even-handed look at the lives of toiling delivery riders. In real life, nearly eight million workers are engaged in India's gig economy. According to a government projection, their numbers are expected to exceed 23 million by 2030. Gig work has produced new opportunities for millions of Indians, but many believe it has also bred newer exploitations.

Samir Patil, who co-wrote Zwigato, told me that research for the film threw up striking insights. "There is optimism [among the gig workers] despite the daily struggles. But we cannot fall into the trap of romanticising it. Nor can we ignore the fact that so many delivery riders feel that a better job is around the corner," he says. "There is also a heart breaking sense that they are on their own and have very low expectations from the [delivery] platforms or the government".

Das says she picked up Sharma after watching a clip of him hosting a Bollywood awards show with his usual elan. It turned out to be an inspired choice. On the comedian's latest show, a food delivery rider in the audience recounted a story about how a couple cancelled a 300 rupees ($3.65; £2.96) order because he was five minutes late. He had earned only 20 rupees that day and waited until midnight for a second order.

"So I just went home, had all the food myself and went to sleep," the man said with a chuckle.

Laughter swept through the audience. Sharma appeared to tear up a little.

BBC News India is now on YouTube, external. to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: