Maharashtra: The Indians taking on giant Saudi-backed refinery

- Published

Manasi Bole is among protesters who do not want the refinery in Ratnagiri

"We don't want this chemical refinery. We will not allow dirty oil from an Arab country to destroy our pristine environment," says Manasi Bole.

She is among thousands of people protesting plans to acquire an expansive laterite plateau - flanked by cliffside fishing villages, mango orchards and ancient petroglyphs - to build the world's largest petrochemical refinery in western India's ecologically fragile Konkan belt.

In late April, angry protests erupted in Ratnagiri district of the western Indian state of Maharashtra when authorities began testing the soil for the mega project to be built by a consortium of Indian state-run oil majors and global giants Saudi Aramco and Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC).

Thousands of villagers, led by women, braved the intense summer temperatures and lay on the roads to prevent officials from entering the site. Many others shaved their heads and went on a hunger strike to mark their dissent.

Click here, external to watch a video about the protests

When talks with the villagers proved unsuccessful, police imposed a curfew on their movement and used batons and teargas to disperse the protesters. Women protesters and anti-refinery activists were detained, some for several days.

Across the region, there's now simmering discontent over what villagers allege were "undemocratic and coercive" tactics by authorities to saddle them with a mammoth industrial project they've vehemently opposed for nearly a decade.

Mounting opposition

Across the villages we travelled to, there was anxiety about the refinery.

"They say the plateau is a barren wasteland, but it's a source of water for our springs, a place where we go to forage for berries, and grow vegetables" Ms Bole said.

Fisherman Imtiaz Bhatkar said he worried about losing his livelihood every day because of the proposed refinery

Aboard his trawler boat, fisherman Imtiaz Bhatkar said he was worried about losing his livelihood every day because of the proposed refinery.

"We won't be allowed to fish in a 10km (6.2 mile) radius because the crude tankers will be moored at sea," Mr Bhatkar said. "Nearly 30,000 to 40,000 people - local and from outside - depend on fishing in just this one village. What will they do?"

Mango growers in the region - famed for the prized Alphonso mangoes - told us the slightest air pollution and deforestation would severely damage their yields given how sensitive the Alphonso variety is to the vagaries of wind and weather patterns.

Mired in politics

Successive state governments in Maharashtra have been expedient in their stance on the refinery. They have supported it when in power and challenged it when in opposition.

Initially planned as a $40bn (£31.6bn) venture, the size of the 60m-tonne-per-annum project has had to be cut by a third because of the long delays in getting it off the ground.

The project was first announced in 2015 to be built in Nanar village, a few kilometres away from the current site in Barsu village in Ratnagiri. The plans were scrapped after it met with stiff opposition from the residents of Nanar, its village council and environmental groups.

The state's previous chief minister Uddhav Thackeray revived it last year, proposing Barsu as the new site.

But out of power now, he has changed his view in support of the locals.

In April, protesters braved intense summer temperatures and lay on the roads to prevent police from entering the site

The present-day government - which comprises of a splintered faction of Mr Thackeray's party and the BJP - says resistance to the project is politically motivated

"This is a non-polluting green refinery. As the industries minister, it is my job to clear the misunderstandings of people who are being misled by external forces," Uday Samant, a state minister told the BBC.

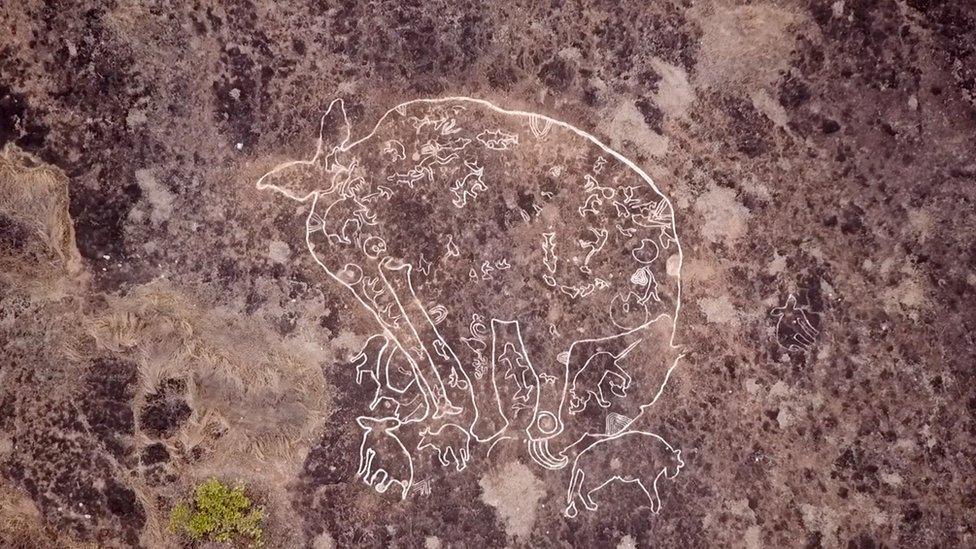

Contrary to widespread claims, there will be no damage to the petroglyphs - or rock carvings - in the region which are now part of UNESCO's tentative world heritage list, he said.

Mr Samant also claimed the government has already acquired 3,000 of the 5,000 acres of land on which the refinery will be built.

What the BBC saw on the ground, however, belied some of his assertions.

The soil testing for the project, for instance, took place barely a few metres away from some of the 170 petroglyphs on the plateau. Letters of objection from at least six local village councils were brushed aside by authorities, saying people from these hamlets didn't own the land on which the refinery would come up.

But locals say they were conned into selling land parcels at throwaway prices to investors - some of which included politicians, police officials and civil servants - without being informed that it would be given away for a refinery project.

"The government is allowing the fate of this region to be decided by 200 investors rather than by its people," said Satyajit Chavan, an anti-refinery activist who spent six nights in jail for social media posts urging residents of the region to join in the protests.

Ecology vs economy

Divisions over the refinery have been drawn on several lines in this tropical idyll, including geography, class and ideological leanings.

Away from the rural interiors, in the town of Rajapur, Suraj Pednekar, a small business owner, insisted the project will vastly improve the fate of Ratnagiri district, an industrial laggard in the country's richest province.

The government's own estimates suggest Maharashtra's GDP will get a 8.5% boost.

Petroglyphs – or rock carvings – in the region are part of the UNESCO’s tentative world heritage list

"Entire generations of young men and women have to go to Mumbai and Pune every year to make a living," Mr Pednekar said. "Villages are being emptied out because there are no jobs. If we get the refinery here and it employs 50,000 people, the population will go up and it will help local businesses. Why should we resist that?"

His views are echoed by several others in the bigger towns whose traditional livelihoods will not be directly affected by the project. But they are drowned out by villagers.

"These so-called jobs will go to educated graduates, not the local fishermen. We don't need such jobs," said Mr Bhatkar.

According to Ms Bole, even if the locals are given work, it will be lower level jobs of sweepers or watchmen.

Across the state, there appears to be growing support for this people's fight.

At a meeting in Pune city recently, local writers, poets, activists and resistance groups vowed to galvanise massive crowds to mount pressure on authorities to scrap the project.

"Our campaign will focus on urging people to not vote for politicians or political parties who are in favour of the refinery," Mr Chavan told the BBC.

From Enron in the 1990s to an attempt by the French to construct a now stalled nuclear power plant here in the early 2000s to various major industrial proposals by Indian conglomerates like the Reliance Group and the Tata Group, over the years, local resistance groups have made several behemoths retreat from the Konkan.

Whether or not the proposed refinery meets the same fate remains to be seen. But crowd after crowd of local villagers told us they will fight till their very last breath till it goes away.

Yet again, it appears, this region has become a faultline between India's economic ambitions and the ecological sensitivities of its people.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here, external to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.