India v Pakistan: An epic battle in Narendra Modi stadium

- Published

India v Pakistan: The body-painted fans in cricket World Cup 'festival'

For the past few days, Arun Hariyani has been painting himself in India's tricolour to drum up attention and try to wangle a ticket to the epic cricket match in India's western city of Ahmedabad.

As the city readies itself rather leisurely for the highly anticipated World Cup showdown against Pakistan on Saturday, Mr Hariyani is arguably its most vibrant cricket enthusiast.

The slender 41-year-old, hailing from a family of textile traders, along with a friend, arrives at a basement near the city's expansive riverfront, carrying a bag filled with acrylic paints and brushes.

Outside a public restroom, Mr Hariyani meticulously paints himself, and later, he adorns his friend, Jagdish Balrampur Swami, with the vibrant Pakistani colours of green. Then they put on retro white sunglasses and strike an array of poses - from the aggressive to the amiable - for pictures.

"We make a team, we make a theme, we get more eyeballs. If we don't get tickets for the game on Saturday, we will stand outside the stadium and spread the message of cricket," says Mr Hariyani.

"But make no mistake about it. We are diehard India fans. I don't even have a favourite Pakistani cricketer."

The Narendra Modi Stadium is the largest cricket stadium in the world

Mr Hariyani wears his patriotism on his skin. INDIA is prominently tattooed on his forehead. His body is a canvas of dedication, adorned with tattoos depicting fighter jets, military helicopters, warships, and valiant soldiers on his back and shoulders. Over the last two years, he has painted himself in the hues of the Indian flag and hoisted the tricolour at the iconic Lal Chowk in Srinagar in Indian-administered Kashmir.

"But this is different. This is the world's fiercest cricket contest," he says.

This time, many argue that the game is as much about politics as it is about cricket, fuelled by India's desire to utilise it as an "economic driver, grand spectacle, and celebration of national character,", external in the words of Barney Ronay, sports writer for The Guardian.

The world's largest cricket stadium, with a 132,000 seating capacity, in Ahmedabad, Gujarat's biggest city, is named after Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The inaugural event held here was a grand reception for Donald Trump, hosted by Mr Modi, in 2020.

During the ongoing six-week-long World Cup, featuring 10 national teams from across the globe, Ahmedabad is hosting the marquee matches, including the opening game, the weekend face-off against Pakistan, and the final on 19 November.

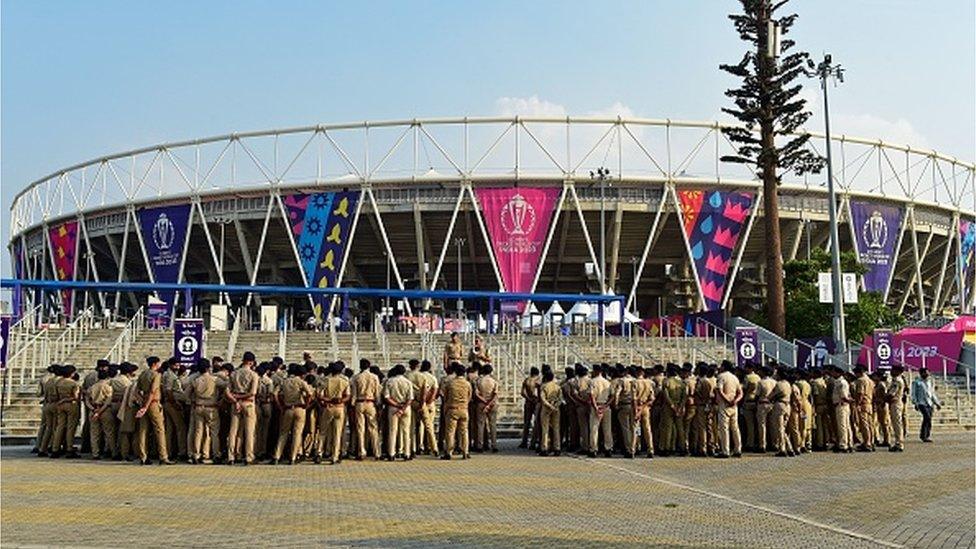

More than 7,000 policemen will be deployed to secure Ahmedabad on match day

Gujarat is the home state of Mr Modi, who, his supporters believe, is primed to win a record third term for his Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in general elections next year. India's cricket board - the richest in the world - is run by Jay Shah, son of Amit Shah, the powerful interior minister and Mr Modi's closest confidant. Author and columnist Suresh Menon calls this World Cup an "extended election campaign".

The World Cup also unfolds against the backdrop of persistently strained relations between India and Pakistan, described by a foreign policy expert as a "cold peace." (The two countries have fought three wars since they became independent nations in 1947.) Pakistan last visited India seven years ago, and only two members of their current team have ever been here before.

In the media-magnified countdown to the game, news networks and social media have attempted to heighten the rivalry, echoing George Orwell's famous description of international sports as "war minus the shooting".

Ahmedabad itself has a history of religious tensions - the last riots, among the worst since Independence, happened in 2001. More than 7,000 policemen, along with nine bomb detection and disposal squads will be deployed to secure the city on match day. Drones will keep an eye from the air. "We also took into account the fact that it will be a sensitive match and it can create communal disturbance," GS Malik, the police chief, told reporters.

Merchandise sellers are bemoaning the lacklustre response in the run-up to the game

The city of more than 8 million people, however, reveals scant signs of public fervour over the game yet. Banners carrying pictures of Indian cricketers are confined to the bustling Motera Road, which runs alongside the stadium. "There is very little enthusiasm," bemoans Amit Pawar, a vendor hawking Indian team merchandise on the pavement outside the venue. "I have only sold 12 jerseys in two days."

The only sparks of excitement come from the arrests of some young men selling counterfeit tickets and unverified accounts of cricket fans feigning medical conditions to secure hospital rooms, their attempts to find hotel accommodations having fallen through.

Cricket historians tell you that even the India-Pakistan rivalry has a rather tepid history in Ahmedabad, which is not exactly a cricketing hub. Here, the rivals have faced each other here only three times since 1987. India has won one, external (20T), lost one, external (ODI) and drawn one, external (Test) game.

However the cricket rivalry continues to be fierce - and it will surely come alive again in a packed arena on Saturday. Tens of thousands of fans will turn up in uniform: the arena will be vast ocean of blue - the colour of the Indian team shirt - with specks of green, the colour of Pakistan's World Cup kit. The tournament has been marred by scheduling delays, ticket sale muddles, and visa delays for visiting Pakistani journalists and fans.

"I believe the intensity of the rivalry has only been sharpened by the keen sense of deprivation. When we played each other frequently, as in the 1980s, the rivalry appeared less intense. Now that we play each other so infrequently, each match acquires an oversize importance and lingers longer in the memory," Shashi Tharoor, an Indian MP who is also a well-known cricket writer, told me.

Cricket fans welcoming Pakistan during a World Cup game in Hyderabad

Clearly, Saturday's match has the potential to be a stunning conclusion to the otherwise lacklustre build-up.

Indian fans will also remember that Ahmedabad has usually brought good luck to India. Legendary batter Sunil Gavaskar got his 10,000th Test run here and became the highest scorer in Test cricket in 1987. Seven years later, all-rounder Kapil Dev picked up his 432nd victim to romp past Richard Hadlee, then Test cricket's leading wicket-taker. In 2013, Sachin Tendulkar became the first batter to cross 30,000 runs in international cricket here.

Also, many believe that with fans on both sides of the border "growing up", there are prospects of an exciting game of cricket.

"There is no longer the filthy enmity which marked the India-Pakistan games in earlier decades. Even if the two sides don't play each other often, fans have matured because they have access to cricket being played by both teams on TV," says Sharda Ugra, a cricket writer.

With at least six teams having an equal chance of making the final, it is too early to predict this World Cup. But if the two rivals meet again on 19 November for the final in Ahmedabad's Narendra Modi Stadium?

"An India-Pakistan final would be a promoter's dream, and its aftermath potentially a security official's nightmare," says Mr Tharoor.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here, external to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: