Same-sex marriage: The lesbian activist seeking equal rights in India

- Published

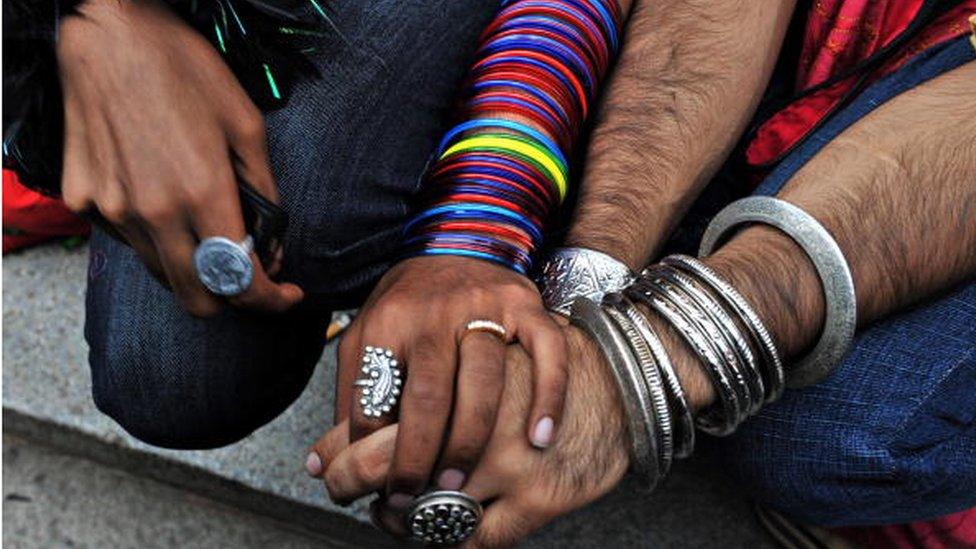

Maya Sharma is one of the petitioners seeking marriage equality in India

With India's Supreme Court due to rule on legalising same-sex marriages in the coming days, Maya Sharma is waiting with trepidation for the verdict.

An LGBTQ+ activist, the 73-year-old lives with her female partner in the western city of Vadodara.

She is among the 21 petitioners, including same-sex couples, trans people and organisations, who are seeking marriage equality. Her plea, filed along with nine others, also wants the right for LGBTQ+ people to choose their families, even outside of marriage.

Ms Sharma doesn't want marriage for herself - in fact, she "despises the concept" and walked out of a heterosexual marriage three decades ago. "The term marriage comes with a lot of associations," she says, preferring to call her relationship a "partnership".

But the verdict, she told the BBC, could play an important role in highlighting the violence faced by LGBTQ+ couples and give them a chance to "choose" their families on their own terms, along with allowing them to marry.

"Hopefully after the petition, people would also start thinking of a more equitable institution than marriage."

Ms Sharma was in school when she first discovered her attraction for women and shared "deep and intimate friendships" with some of them. But "the world was too heterosexual" at the time to accept a lesbian relationship, she said.

This changed when she moved to Delhi in the 1960s after college and began working for a women's rights collective. There, she encountered several women who were either stuck in abusive marriages or were secretly in love with other women. The experiences "reminded her of her own desires".

Same-sex relations are still a taboo in India

At that time, lesbian relationships were still a taboo and considered highly unusual in India - they still are. Ms Sharma said there were ripples of change every now and then: for instance, in 1988, two policewomen made headlines after they married each other. A few lesbian couples also entered into "partnership agreements" or informal contracts, vowing to stay together.

But the community continued to face backlash. Even the female constables, Ms Sharma pointed out, were eventually suspended from their services without any notice or explanation.

One of the first pivotal moments, she said, came in 1991 when non-profit Aids Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan released a 70-page report, which is widely believed to be the first document on gay rights in India, to counter stigma around same-sex relationships.

Titled Less Than Gay, and popularly known as "the pink book", the document made a list of demands, including decriminalisation of gay sex, marriage equality and certain civil and sexual rights for trans people.

The pink book did not get much public support but it did give Ms Sharma courage in her own life to end her marriage of 16 years.

She said it was not her sexuality, which she was still coming to terms with, that drove her to make the decision but the fact that she could "not digest how unequal and oppressive marriage was".

"So I packed a small suitcase and left without informing my husband."

A few years later, when she fell in love with a woman, she found herself wishing once again that "the world was different" and more accepting of same-sex relationships.

"It is one thing to know yourself. But when you fall in love, then it is one step forward," she said.

She continued to wrestle with her feelings until 1998, when the film Fire released in India.

Starring renowned actors Shabana Azmi and Nandita Das, the film was one of the first in Bollywood to portray a lesbian relationship, and sparked huge protests. Political parties vandalised theatres and those who went to watch the film were attacked by protesters.

The backlash sparked counter-protests from LGBTQ+ groups. Ms Sharma made a poster, which said "Indian and Lesbian", and stood in front of the iconic Regal Cinema in Delhi along with others.

She was initially scared that people would recognise her, but was later emboldened by the impact the protests had on the country.

"For the first time, the word lesbian was making newspaper headlines. Slowly, my fear was not mine alone. We had reached a point where we could say, 'Yes, we exist, what can you do about it'."

The Supreme Court's verdict will affect millions of LGBTQ+ people in India

However, her activism had repercussions - she had to quit her job at a trade union after it accused her of "spoiling their image".

She moved to Vadodara and joined another grassroots organisation working on women, lesbian, bisexual and trans people's rights.

Ms Sharma believes that court battles have played an important role in expanding the rights of LGBTQ+ people and "what went behind the battle has often mattered more than the final outcome".

For instance, before the Supreme Court decriminalised gay sex in 2018, she says the LGBTQ+ community had been "scattered and divided". This was a rare moment when the entire community "came together with an understanding".

Other judgements along the way also helped the movement. In 2014, the Supreme Court recognised transgender people as a third gender in a landmark ruling, granting certain rights to them and giving them the power to "advocate with the government".

Ms Sharma says if the Supreme Court legalises same-sex marriage, it would spark further change. But no matter what the judgement, the movement will still have more work to do, she adds.

"The quest for law is on one side and societal change is on the other. But it is a beautiful thought that the two could ever meet."

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here, external to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: