Arvind Kejriwal: The maverick leader who took on India's Modi

- Published

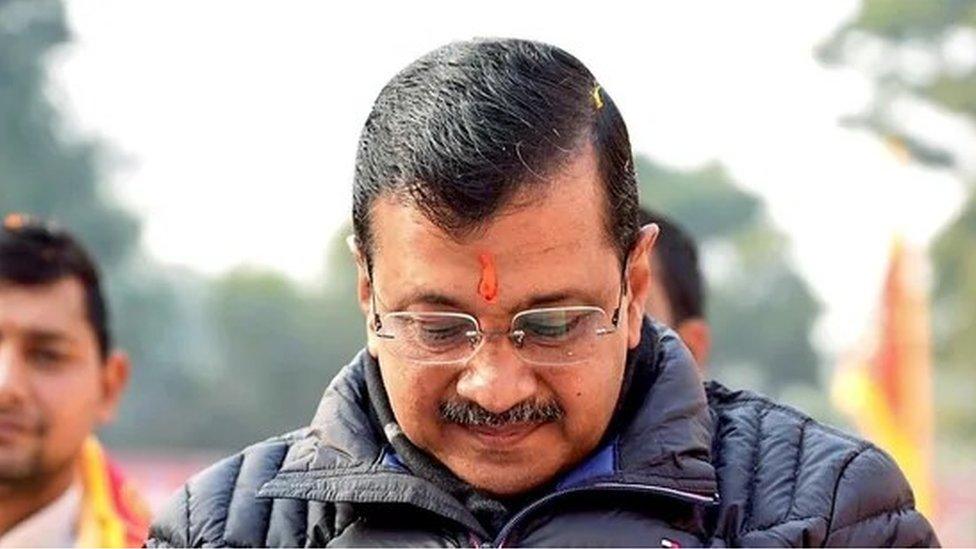

Mr Kejriwal is the third AAP leader to be arrested over the alleged corruption case

When Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal was arrested on Thursday on claims of corruption, it came as no surprise.

Months earlier, in November, Mr Kejriwal's Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) had run a door to door campaign, asking residents of India's capital whether he should resign or run his government from jail.

Mr Kejriwal and other senior party leaders face corruption accusations under investigation by India's powerful federal financial crime agency, the Enforcement Directorate (ED)

He is the third AAP leader to be arrested over a case related to a now-scrapped liquor policy in Delhi. This policy involved the government relinquishing control of the liquor market to private vendors.

Mr Kejriwal has denounced the investigation, arguing that the ED had failed to frame "specific" charges against him and called the summons "generic" and "illegal".

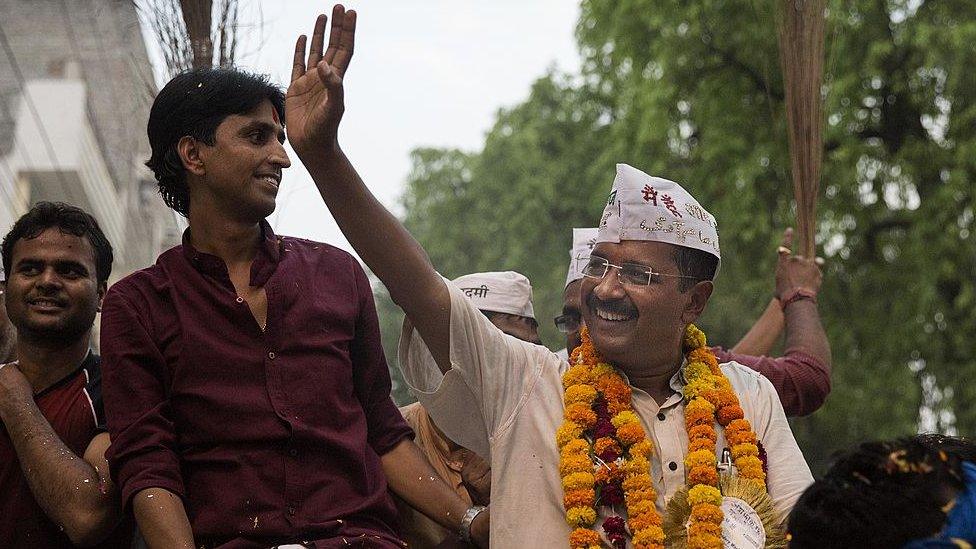

Mr Kejriwal's arrest, contrasting his anti-corruption campaign that took India by storm in 2011, comes less than a month before India's general elections, starting on 19 April. His AAP is part of the 27-party INDIA alliance aiming to challenge the governing BJP.

Mr Kejriwal and his close confidant Manish Sisodia (left) - Mr Sisodia was arrested last year

In just over a decade, AAP, despite being a newcomer, has emerged as a formidable force.

It has secured successive victories in Delhi's state elections since 2013 and expanded its influence by winning crucial polls in Punjab, where discontent against federal government policies prevails.

The party is contesting four of the seven parliamentary seats in the capital in the upcoming general election. In 2019, it lost all seven seats to the BJP. However, the AAP swept 62 of the 70 assembly seats in Delhi in 2020.

Who is Arvind Kejriwal?

A mechanical engineer from the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, Mr Kejriwal later served as a government officer in the Income Tax department.

He gained prominence for his work with Parivartan, an organisation that popularised the use of India's Right to Information (RTI) law which allows people to access information held by the government.

In 2011, Mr Kejriwal backed social crusader Anna Hazare's (right) hunger strike

In 2006, he received the Ramon Magsaysay award, external for using the RTI to "empower citizens to monitor and audit government projects and inspire local community action".

In 2011, Mr Kejriwal backed social crusader Anna Hazare's hunger strike for the establishment of a citizen's ombudsman to investigate corruption. Inspired by the campaign's success, which stirred India, he founded the AAP, pledging to eradicate corruption.

Mr Kejriwal became the chief minister of Delhi for the first time in 2013. However, he resigned after 49 days when his party failed to pass the ombudsman bill in the assembly.

His resignation proved strategic, portraying him as a principled politician willing to give up high office in the fight against corruption.

This bolstered his party's growth, leading to a sweeping victory in the 2015 Delhi assembly elections. In 2020, his party secured another victory in Delhi.

The fight to retain power

The AAP claims that the BJP seeks to topple its Delhi government despite its dominant position in the legislative assembly. Along with other opposition parties, it accuses the BJP of targeting opposition leaders through central agencies.

These agencies are investigating money-laundering allegations against the chief ministers of three southern states and other political opponents. The BJP denies any political motivation behind the investigations.

Mr Kejriwal took on Mr Modi in Varanasi in the 2014 general election and lost

Mr Kejriwal's party has faced numerous investigations.

The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) arrested Manish Sisodia, Mr Kejriwal's former deputy chief minister, in February last year accusing him of favouring some cartels after the liquor policy came into effect.

Similarly, AAP's top lawmaker Sanjay Singh was arrested last October for allegedly accepting money from middlemen of liquor barons who profited from the same policy.

In his third term as chief minister, Mr Kejriwal faced new challenges.

The Hindu nationalist BJP emerged as AAP's main rival in Delhi, prompting the chief minister to appeal more to Hindu religious sentiments.

Also, anti-corruption rhetoric alone wasn't sufficient for AAP's electoral success in Delhi, say analysts. The party's popularity now relies heavily on welfare schemes such as free electricity and water for the poor.

It remains to be seen whether AAP's emphasis on its welfare schemes will resonate in the upcoming polls. "I will open as many schools as the number of summons issued to me," Mr Kejriwal said in February.

The controversial liquor policy

Mr Kejriwal's party had said that the new liquor policy would curb black market sales, increase revenues and ensure even distribution of liquor licences across the city.

However, the policy was later withdrawn after Lieutenant Governor (LG) Vinai Kumar Saxena accused the AAP of exploiting rules to benefit private liquor barons. Mr Saxena, appointed by the federal government, had clashed with the Delhi government on multiple occasions before the controversy over the excise policy.

Following Mr Saxena's allegations, federal agencies started investigating the policy and the alleged kickbacks received by AAP leaders from its misuse.

Read more India stories from the BBC: