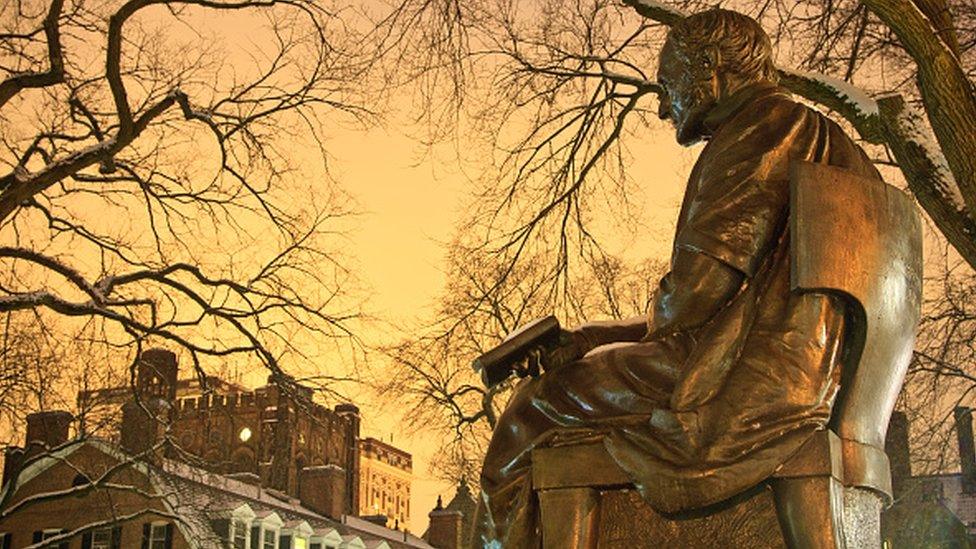

Elihu Yale: The cruel and greedy Yale benefactor who traded in Indian slaves

- Published

An 18th Century British painting of Elihu Yale (centre) in which he's seen with a child slave

Last month, Yale University issued a formal apology for the links its early leaders and benefactors had with slavery.

Since then, one name that has come under intense scrutiny in India is that of Elihu Yale, the man after whom the Ivy League university is named.

Yale served as the all-powerful governor-president of the British East India Company in Madras in southern India (present-day Chennai) in the 17th Century and it was a gift of about £1,162 ($1,486) that earned him the honour of having the university named after him.

"It's equivalent of £206,000 today if you adjust it for inflation," historian Prof Joseph Yannielli, who teaches modern history at Aston University in Birmingham and has studied Yale's links with the Indian Ocean slave trade, told the BBC.

It was not an enormous sum by today's standards, but it helped the college construct an entire new building.

Often described as a connoisseur and collector of fine things and a philanthropist who generously donated to churches and charities, Elihu Yale is now in focus as a colonialist who plundered India and - worse - traded in slaves.

The university's apology comes after more than three years of investigation into its dark past. Led by Yale historian David Blight, a team of researchers delved into the "university's history with slavery, role of slaves in construction of a Yale building or whose labour enriched prominent leaders who made gifts to Yale", the university said in a statement.

The apology was accompanied by the release of a 448-page book, external - Yale and Slavery: A history - by Prof Blight that gives an insight into just how much Elihu Yale profited from slavery.

"The Indian Ocean slave trade, which eventually matched the Atlantic [slave trade] in size and scope, did not become so extensive until the 19th Century. But on the Indian subcontinent, the trade in human beings along its coasts as well as inland and to islands was very old," he writes, adding that Yale "oversaw many sales, adjudications, and accountings of enslaved people for the East India Company".

Prof Yannielli says the Atlantic trade saw 12 million slaves sold over 400 years. The Indian Ocean trade, he believes, was bigger as it covered a much larger geographical area, linking South East Asia with the Middle East and Africa - and went on for much longer.

Yale is one of the major Ivy League universities in the US

The investigation of this past is important. Founded in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher learning in the United State and counts a number of US presidents and other eminent people among its alumni.

And it's well documented that starting in 1713, Elihu Yale sent hundreds of books on theology, literature, medicine, history and architecture, a portrait of King George I, fine textiles and other valuable gifts to the Collegiate School of Connecticut. The money raised by selling them was used to construct a new three-storey building which was named Yale College in his honour.

Historian and family member Rodney Horace Yale who wrote a biography of Elihu Yale in the 19th Century says his "donation made the precarious existence of Yale college a blessed certainty".

It also bought Yale immortality - even though there are no direct descendants of his, the Ivy League university perpetuates his name.

In its apology, the university said it would "work to enhance diversity, support equity and promote an environment of welcome, inclusion, and respect" and undertake work to "advance inclusive economic growth in New Haven" where 30% of the population is black. But it did not say that a name change was on the cards - and it has rejected calls in the past to do so.

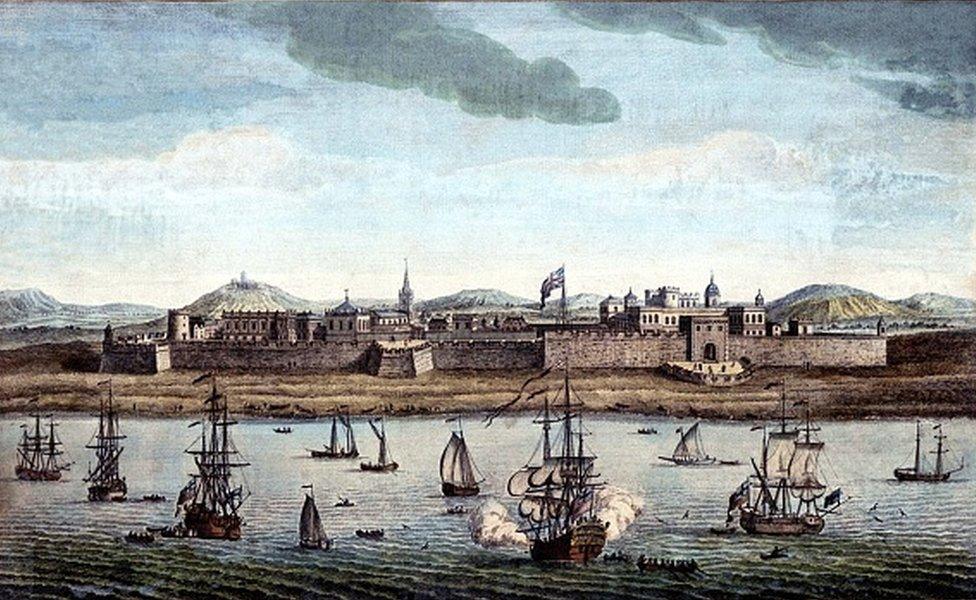

Born in Boston in April 1649, Elihu Yale moved with his family to England when he was three. He arrived at Fort St George, the White colony in Madras, as a young man in 1672 with a clerical job with East India Company.

The salaries offered by the company were "notoriously and ludicrously small - from the governor's at £100 a year down to the apprentices' at £5", Rodney Horace Yale wrote. He and other historians say its employees engaged in all sorts of trading of their own for private profit.

Over a quarter of a century, Yale rose through the ranks, finally being appointed the governor-president in 1687 - a job he did for five years until 1692, when he was sacked for "using company funds for private speculation, arbitrary government and neglecting duty".

In 1699 when he returned to England, the 51-year-old was a hugely wealthy man. He built "a stately home" in Queen's Square on Great Ormond Street and filled it with arts and artefacts of great value.

Upon his death in July 1721, British papers described him as "a gentleman known for his extensive charity". But historians say he was also known during his time in Madras for his cruelty and greed.

Elihu Yale arrived at Fort St George, the White colony in Madras, as a young man in 1672 with a clerical job with the East India Company

His successors accused him of corruption and unusual deaths of several of the council members when he was governor and, on one occasion, he was accused of ordering the hanging of one of his stable grooms "for riding a favourite horse of his without his permission", Rodney Horace Yale wrote.

The historian says there's some doubt about the evidence in the case, but adds that it does not "disagree with his character".

"His surroundings must be his most effective defence for a record of arrogance, cruelty, sensuality and greed while in power at Madras," he wrote.

But Rodney Horace Yale glosses over his ancestor's role in the slave trade - something that many other biographers of Elihu Yale and recent historians are also accused of doing.

Prof Yannielli, who's combed through the colonial records of Fort St George, says "it's all there in black and white" and there's no denying that "Elihu Yale was an active and successful slave trader".

Prof Yannielli wouldn't hazard a guess on how much money Yale made from slavery because it "ebbed and flowed" and also because he traded in other things such as diamonds and textiles which made "it hard to disentangle the profits he made from each trade". But, he believes, it was quite a substantial chunk of his fortune.

"I can say his capacity to make money was enormous. He was in charge of directing the Indian Ocean slave trade. In the 1680s, a devastating famine [in southern India] led to a labour surplus and Yale and other company officials took advantage of it, buying hundreds of slaves and shipping them to the English colony on Saint Helena," he told me.

Yale, he adds, "participated in a meeting that ordered a minimum of 10 slaves sent on every outbound European ship. In just one month in 1687, Fort St George exported at least 665 slaves. As governor-president of the Madras settlement, Yale enforced the 10-slaves-per-vessel rule".

Once the headquarters of East India Company's Madras settlement, Fort St George currently houses Tamil Nadu assembly and other government offices

A former student at Yale, Prof Yannielli first started digging into Elihu Yale's association with slave trading over a decade ago when he came across an image of the governor being waited upon by a collared slave.

That famous painting, he says, is one of the most damning pieces of evidence that connects Yale to slavery. Dated, external between 1719 and 1721, it shows Yale with three other white men being served by a "page" - a term that generally means a servant but in this case, a euphemism for a slave.

"Slavery was ubiquitous in England at the time. It's not clear whether he owned the slave himself or was it a member of his family [who was the owner]. But the presence of the child in the frame, serving him and others wine, shows that slavery was integrated into his day-to-day life."

Prof Yannielli says the reason why some of Yale's earlier biographers have underplayed his links to slavery could be because of a lack of access to historical material in the past.

But since detailed minutes of East India Company's meetings are now available digitally, the more recent scholars who have chosen to overlook the evidence is "because either they didn't want to see it or may not have considered it important in the pre-Black Lives Matter era".

Prof Yannielli also rubbishes claims that Yale was an abolitionist who ordered prohibiting slave trade from Madras when he was governor.

"Saying that he actually ended slavery is an attempt to burnish his image. If you look at the original documents, it was India's Mughal ruler who told the company to shut it. But Yale was back at it soon, ordering transport of slaves from Madagascar to Indonesia a year later.

"Resistance to slavery and imperialism started in the 15th Century and there were abolitionists. But Yale definitely wasn't one."