Ukraine war: The Indian men traumatised by fighting for Russia

- Published

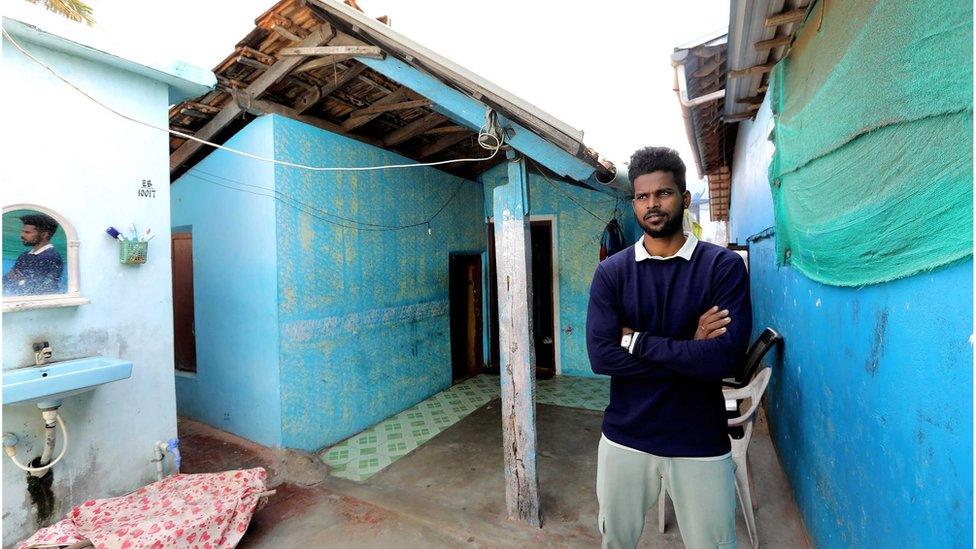

David Moothappan is among dozens of Indians who were duped into fighting in the Russian army

In October last year, David Moothappan saw a Facebook advertisement offering jobs as security guards in Russia.

The promised monthly salary - 204,000 roubles ($2,201; £1,739) - seemed a huge amount to the school-dropout fisherman from the southern Indian state of Kerala.

Weeks later, Mr Moothappan, 23, found himself on the warfront in the Russian-held city of Donetsk in eastern Ukraine.

"It's death and destruction everywhere," he says, when asked about his time there.

He and another man from Kerala managed to return home last week. They are among several Indians who were duped by agents into fighting for Russian forces in the country's war with Ukraine over the past few months.

A few have managed to make their way back home but others are still stuck in Russia. Most of them are from poor families and were lured with the promise of jobs, sometimes as "helpers" in the Russian army. At least two Indians have died so far in the war.

India's foreign ministry has said it is "pressing very hard with the Russian authorities" to bring back its citizens who have been tricked into fighting in the war. Last week, foreign minister S Jaishankar called this, external "a matter of very, very deep concern" for India. The BBC has emailed the Russian embassy in India for comment.

Warning: This article contains details some readers may find distressing.

Mr Moothappan is relieved to be back home in the fishing village of Pozhiyoor in Kerala, but says he can't forget what he saw in the war.

"There were body parts strewn all over the ground," he says. Distraught, he started vomiting and almost fainted.

"Soon, the Russian officer commanding us told me to return to the camp. It took hours for me to recover," he says.

He says he broke his leg around Christmas while fighting in a "remote place" - his family, he says, didn't know about his situation at that time.

Mr Moothappan spent two and a half months in different hospitals in Luhansk, Volgograd and Rostov before recovering partially.

In March, a group of Indians helped him reach the country's embassy in Moscow, which then arranged for him to travel back home.

Prince Sebastian came back to India after he was injured in the war

Some 61km away in Anchuthengu, another fishing hamlet in Kerala, Prince Sebastian has a similar story of escape - and trauma - to tell.

Duped by a local agent, he was deployed in a group of 30 fighters in the Russian-occupied eastern Ukrainian town of Lysychansk. After just three weeks of training, he says he was sent to the frontline with several weapons including an RPG-30 (a handheld, disposable rocket-propelled grenade launcher) and bombs, which prevented him from moving quickly.

Fifteen minutes after he reached the front, he says a bullet fired from close range deflected off the tank he was in and pierced below his left ear. He fell - on to what he realised was a dead Russian soldier.

"I was shocked and I couldn't move. After an hour, as the night fell, another bomb exploded. It badly injured my left leg."

He spent the night in a trench, bleeding. He escaped the next morning and subsequently spent weeks in different hospitals.

He then got a month's leave to rest. During this time, a priest helped him contact the Indian embassy which then issued him a temporary passport and arranged for his return home.

He says two of his friends who went with him, also fishermen, are still missing. Neither he nor their families have heard from them in weeks.

Officials in Kerala say they have so far received complaints from the families of four men - Mr Moothappan, Mr Sebastian and his two friends - about being duped by agents.

Mr Sebastian says he and his friends went to a local agent in their village to check if they could find jobs somewhere in Europe (the man is currently absconding).

The agent suggested Russia, speaking of a "golden opportunity" to work as a security guard for a monthly salary of 200,000 rupees ($2,402; £1,898). They agreed instantly.

The friends paid 700,000 rupees each to him for a Russian visa. On 4 January, they reached Moscow, where an Indian agent identified as Alex, who spoke their language, Malayalam, welcomed them.

They spent the night in a flat, following which a man took them to a military officer in the city of Kostroma, 336km (208 miles) away, where they were made to sign a contract in Russian, a language they couldn't read, Mr Sebastian said.

Three Sri Lankan recruits also joined them there. Then the six men were taken to a military camp in the Rostov region, which borders Ukraine. The officers took their passports and mobile phones.

Prince Sebastian says two of his friends are missing - their families are waiting anxiously for news

The training started on 10 January. In the following days, they learnt how to use handheld anti-tank grenades and what to do if they were injured.

After this, they were taken to a secondary base known as the Alabino Polygon. There, the training continued for 10 days, "day and night".

"All kinds of armaments were waiting for us there," Mr Sebastian said. "I started enjoying the weapons like toys."

But the brutal reality of the war hit him on the battlefield.

Now, he is hoping to resume fishing. "I have to repay the money I borrowed from lenders and restart my life," he says.

In Pozhiyoor, Mr Moothappan hopes to do the same.

"I was engaged to a girl in my village when I left. I told her I'll return with money and build a house before our marriage," he said.

Now the couple have decided to wait for two more years as Mr Moothappan tries to rebuild his life.

But he's happy that at least he didn't kill anyone in his time on the battlefield.

"One time, the Ukrainians were some 200m away. We were asked to go on the offensive but I didn't fire a single shot at them," he said. "I can't kill anybody."