Manthan: The Indian film at Cannes made by half a million farmers

- Published

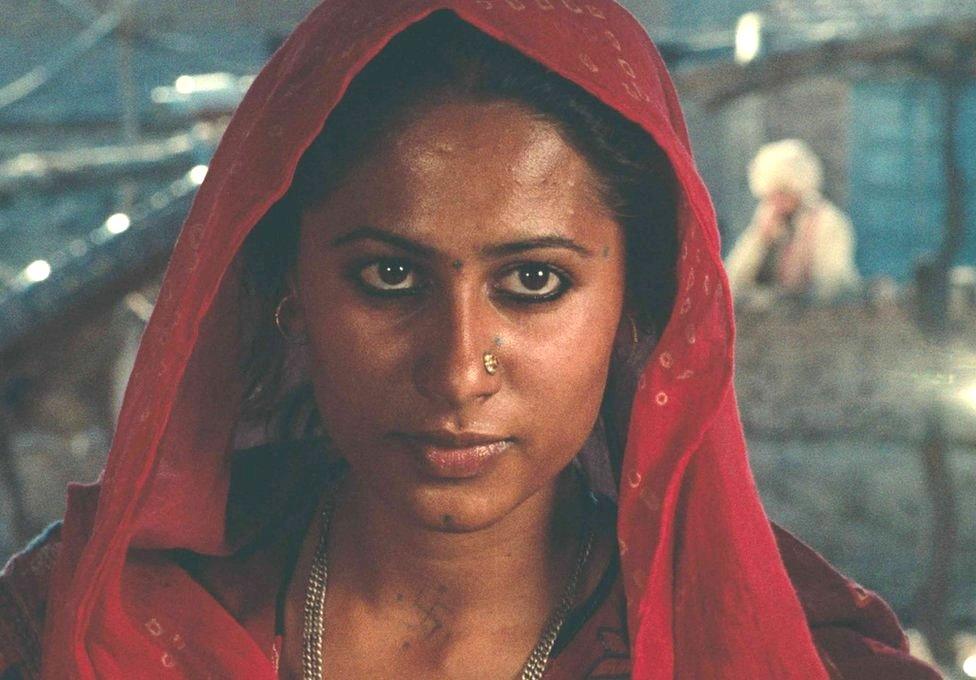

Smita Patil played the role of an "untouchable" village woman in Manthan

In the mid-1970s, half a million dairy farmers in India's western state of Gujarat contributed two rupees each to make a ground-breaking film.

Manthan (The Churning), directed by venerated filmmaker Shyam Benegal, became the country's first crowd-funded film.

The 134-minute 1976 film was a fictionalised narrative of the genesis of a dairy cooperative movement that transformed India from a milk-deficient nation to the world's leading milk producer. The story drew inspiration from Verghese Kurien - known as the "Milkman of India" for revolutionising milk production in the country. (India today accounts for nearly a quarter of the global milk production.)

Nearly 50 years after it was made, a pristinely restored Manthan is receiving a red-carpet world premiere this week at the Cannes Film Festival, alongside classics from Jean-Luc Godard, Akira Kurosawa and Wim Wenders. Restoring the film was a challenge, according to Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, award-winning filmmaker, archivist and restorer.

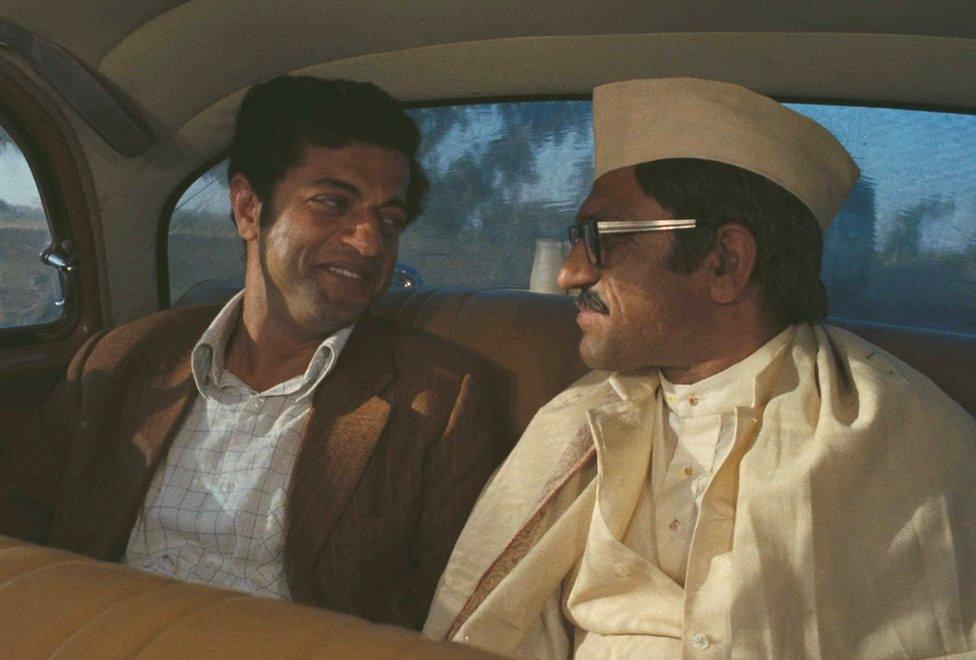

Girish Karnad (left) plays a veterinary doctor who meets a private dairy owner played by Amrish Puri (right)

All that remained of Manthan was a damaged negative and two faded prints. The negative had been ravaged by fungus, leaving vertical green lines across many sections. The sound negative was entirely destroyed, forcing the restorers to rely on the sound from the sole surviving print.

The restorers salvaged the negative and one of the prints. They borrowed and digitised the sound from the print, and repaired the film. The scanning and digital clean-up were conducted at a Chennai lab under the supervision of a renowned Bologna-based film restoration lab, with both Benegal and his long-time cinematographer Govind Nihalani overseeing the project. The film's sound was fixed and improved at the Bologna lab.

Some 17 months later, Manthan was reborn in ultra high definition 4K. Benegal, one of the doyens of Indian cinema, says the film remains very close to his heart.

"It is wonderful to see the film come back to life almost like we made it yesterday. It looks better than the first print," the 89-year-old filmmaker says.

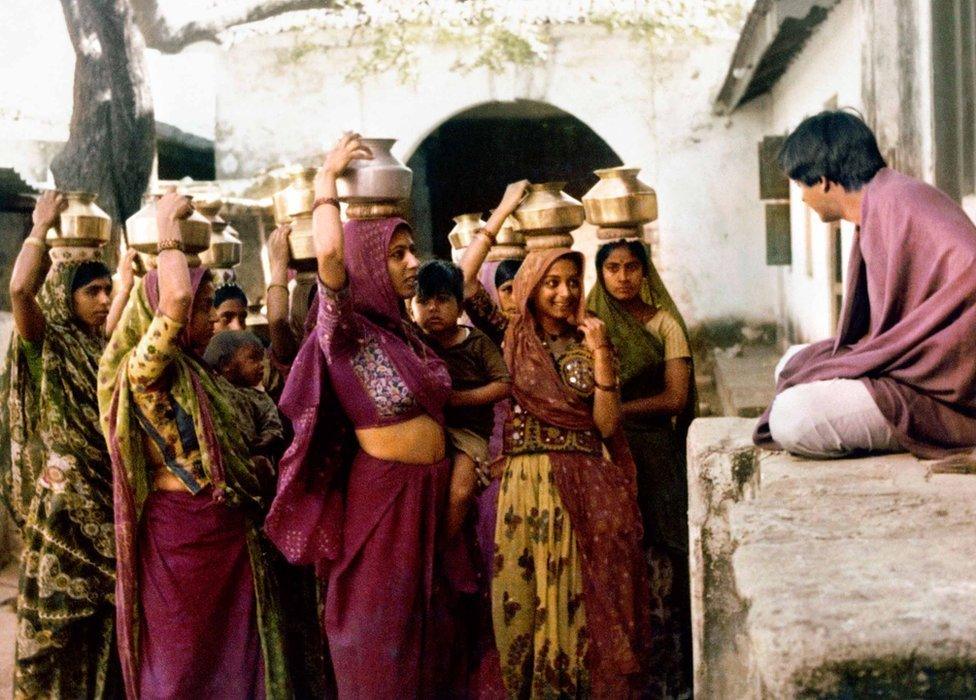

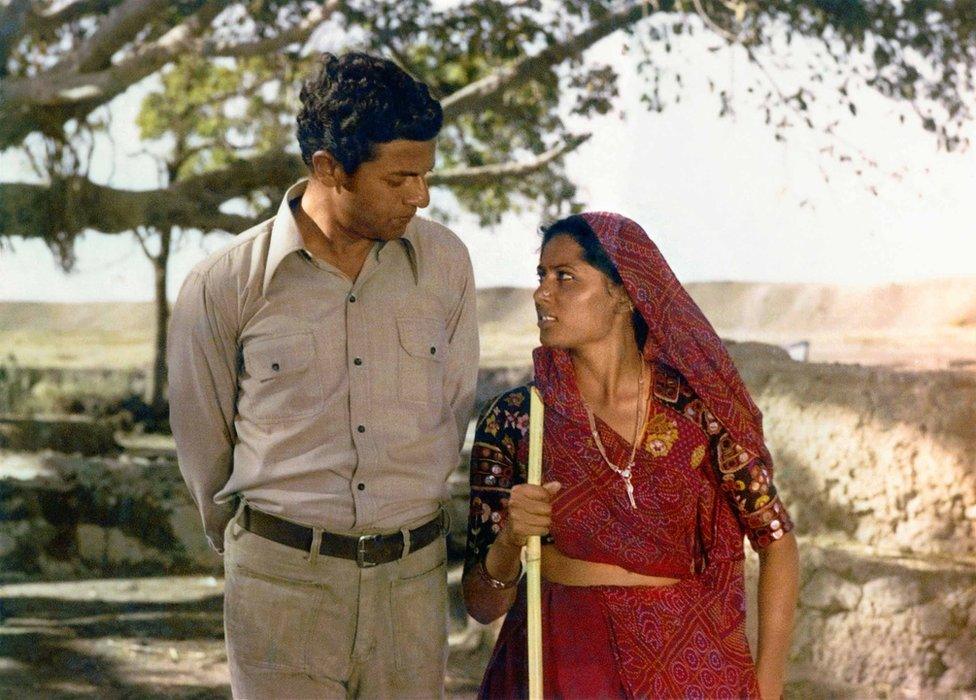

Actor Naseeruddin Shah learnt to make cow dung cakes and milk a buffalo during the making of the film

Benegal recounts that, egged on by Kurien, he had produced several documentaries on Operation Flood, external - India's milk revolution - and rural marketing initiatives. When he suggested a feature film to Kurien, saying that documentaries mainly reached those "converted to the cause", Kurien balked. He told Benegal that there were no funds available to make the film, given his refusal to accept money from farmers.

Under the cooperative model, small farmers would bring and sell milk in the mornings and evenings to a network of collection centres in Gujarat. The milk was then transported to dairies for processing into butter and other products.

Kurien proposed that the collection centres deduct two rupees from each farmer, enabling all of them to become producers. The collected funds financed the making of the film. "The farmers readily agreed because we were telling their story," says Benegal.

Manthan, external boasted a stellar cast, featuring Girish Karnad, Smita Patil, Naseeruddin Shah, Amrish Puri, Kulbhushan Kharbanda and Mohan Agashe in key roles. Vijay Tendulkar, a prominent Indian playwright, contributed multiple scripts, with Benegal selecting one for the film. Renowned composer Vanraj Bhatia scored the music.

Benegal (left) oversaw the restoration of the film by Shivendra Singh Dungarpur (right) and his team

In the film, a city-bred government veterinary doctor and his team arrive in a deeply divided village in Gujarat with plans to start a dairy cooperative. As he starts his work, the vet is caught in the tumultuous politics of change and faces challenges from a private dairy owner, the village head and a volatile local milkman.

"Manthan is a microcosmic picture of transformative politics... Benegal offers a brilliant social critique of a situation in which government bureaucrats enter a village and try to change the social and economic perspectives of its inhabitants," wrote Sangeeta Datta, author of World Director Series: Shyam Benegal.

Money was tight and the 45-day shoot was a challenge. Nihalani remembers using a "patchwork of different film stocks" to shoot the film. The crew lived as a close-knit family in the village, where many residents also acted in the film. The cast did not change their costumes throughout the shooting, so "that they looked worn in the village", said Datta.

Many villagers of Gujarat acted in the film, which was produced by milk farmers

Naseeruddin Shah, who began his acting career with Benegal and later became one of India's best-known actors, remembers living the film during its making.

"I lived in a hut, learnt to make cow dung cakes and milk a buffalo," he says. "I would carry the buckets and serve the milk to the unit to get the physicality of the character." Shah, who will present the film at Cannes, also wore the same cotton shirt throughout the shoot.

Kurien released the film initially in Gujarat to a rousing reception. "The film did brilliantly because its largest audience was also the film's producers. Every day we had this incredible sight of truckloads of people coming in from all over to see the film," says Benegal. More copies of this film were produced than any other in India, spanning formats from 35mm to 8mm, Super 8, and later, video cassettes. Manthan was widely shown around the world, including at the UN General Assembly, and won a National Award at home.

Manthan's success gave Kurien another idea. Using the film to propagate the milk revolution, he distributed 16mm prints to villages nationwide, urging farmers to establish their own cooperatives. In real life imitating reel life, he sent teams comprising a vet, a milk technician and a fodder specialist to distribute and show the film to farmers.

Benegal says Manthan "serves as a powerful reminder of cinema's ability to drive change"

Benegal says Manthan "serves as a powerful reminder of cinema's ability to drive change". The film also retains surprising relevance today, as it explores a range of issues that continue to bedevil contemporary India.

Trains, still notorious for running late, set the stage for the film's opening scene. A passenger train, carrying the doctor and his assistant, pulls into a tranquil village station. Locals, slightly tardy, rush down the platform to welcome their guests with garlands.

"We are sorry," a breathless villager tells the vet. "The train arrived on time."