Chum Mey: Tuol Sleng survivor

- Published

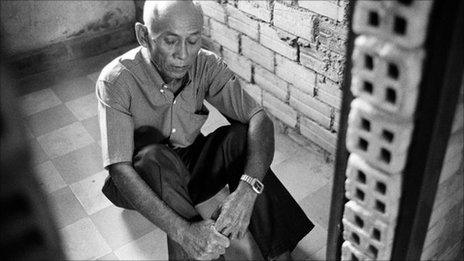

Chum Mey visits his former cell in the Tuol Sleng prison

For more than three decades Chum Mey has carried the physical and emotional scars inflicted on him by agents of Cambodia's Khmer Rouge.

He is one of a only handful of people to have survived Tuol Sleng prison, code-named S-21 - the regime's interrogation centre and site of torture and mass murder.

Last year, from behind bullet-proof glass in a Phnom Penh courtroom, Chum Mey finally told his story to the world.

He was a leading witness in the first trial of a senior Khmer Rouge figure, Kaing Guek Eav, also known as Comrade Duch.

Duch was the head of Tuol Sleng, were as many as 17,000 men, women and children were detained and then killed.

Chum Mey's testimony to the United Nations-backed court could perhaps help bring them a degree of long-delayed justice.

Forced exodus

In 1975, Chum Mey - originally from Prey Veng province - was working in Phnom Penh as a mechanic. He was married with three young children.

Cambodia at that time was in political turmoil, with the leaders of a 1970 military coup locked in civil war against Pol Pot's forces.

On 17 April 1975 the Khmer Rouge captured Phnom Penh.

"When they entered everybody including myself raised a white flag to congratulate them; everybody cheered," Chum Mey told the war crimes tribunal.

Just hours later, Khmer Rouge representatives went door-to-door telling people to evacuate to the countryside. Chum Mey said those who did not co-operate were shot dead.

He gathered his wife and children and joined the exodus. His two-year-old son fell ill and died during the journey. Chum Mey was forced to bury him in a shallow grave and move on.

Later, he was sent back to the capital by the Khmer Rouge to repair sewing machines for a co-operative manufacturing the new revolutionary uniform, black pyjamas.

On 28 October 1978 he and other workers were told they were being sent to fix vehicles for an offensive against Vietnam.

In reality, Chum Mey was about to enter the darkest period of his life, as he was taken to Tuol Sleng.

Conspirator

There he was imprisoned in a brick cell about two metres by one metre wide, blind-folded and shackled to the floor.

For 12 days and nights, Chum Mey says he was tortured, as his interrogators tried to make him confess to spying for the US and Russia.

"If you refuse to confess I'll beat you to death. You must tell the truth then I won't kill you. If not I must kill you," he quoted his tormentors as saying.

He was whipped repeatedly about the body with a switch of bamboo sticks. When he held up his hands to try to shield himself his fingers were broken.

His toenails were pulled out with pliers while his legs were shackled. When he still refused to confess, the nails were twisted and pulled off his other foot.

Finally, Chum Mey said he was subjected to electric shocks several times with a wire from a 220-volt wall socket.

On each occasion he passed out. When he came round, he was asked again to confess. Eventually he said he confessed to anything so that the torture would be over.

In his confession Chum Mey wrote that he was working for the CIA and had recruited dozens of agents in Cambodia.

He gave the names of dozens of acquaintances, innocent men and women who, it is presumed, were later arrested, tortured and murdered.

"People who had been arrested and killed previously had implicated me, and I implicated others. So did other people.

"It was just like rear waves pushing the front waves forward. So people would die one after another, after another, after another," he said in a BBC interview in 2002.

Further tragedy

Chum Mey believes he was allowed to live because he was of use to the regime, fixing sewing machines in the prison workshop.

At night he was chained to a long iron bar with 40 other prisoners. He says they were forced to live in silence.

Chum Mey hopes the war crimes trial might bring some belated justice for himself and his country

"When I wept I could not make any noise. I wept a lot and I had no more tears to weep, I was only waiting for the day that I would be killed," he later told the war crimes trial.

On 7 January 1979, Vietnamese troops captured Phnom Penh from the Khmer Rouge, and the prison staff fled.

Chum Mey was marched at gunpoint by prison guards into the provinces, where he had a chance meeting with his wife, and held for the first time his fourth child - a boy, just two months old.

For two days they travelled together to an isolated area with a group of other prisoners. They were then ordered to walk into a paddy field, where their captors opened fire on them.

The soldiers shot dead his wife and baby. Chum Mey escaped alone and hid in a forest.

Justice

"I cry every night. Every time I hear people talk about the Khmer Rouge it reminds me of my wife and children," Chum Mey told the public gallery at Duch's trial.

He has said that only the court can help to "wash away" his suffering.

Last year he was elected as the head of the newly-formed Association of Victims of the Khmer Rouge Regime.

Speaking to the BBC just weeks before the verdict, Chum Mey said he hoped Duch would be sentenced to life in prison.

But he said he felt cheated by the court, which he said seemed to place most of the responsibility for crimes committed on those perpetrators already dead, rather than focusing on the accused.

Although the trial has not brought closure for Cambodians, he told the BBC's Guy De Launey he was satisfied that a judicial system was now in place.

Most days Chum Mey can be found at the former prison, which is now a genocide museum, housing the photographs and written confessions of many of the victims.

"I come every day to tell the world the truth about the Tuol Sleng prison... so that none of these crimes are ever repeated anywhere in the world."