Is development killing Tibet's way of life?

- Published

Tibetans have struggled to safeguard their way of life, but can they continue?

High in Tibet's mountains there are fears that an ancient way of life is slowly dying.

China is bringing development to Tibet, changing it, trying to make it modern, but some Tibetans are worried that their region's unique identity is being eroded.

Our was a rare, Chinese government-controlled trip to Tibet.

Our schedule and our movements were almost entirely controlled by official minders who rarely let us out of their sight.

Almost all the people we spoke to were hand-picked to show us China's view of Tibet.

Handsome wages

One way things are changing in Tibet is evident at the 5,100 Mineral water factory four hours drive outside Lhasa.

Pubu Zhaxi works in a mineral water factory

Bottles of mineral water fly along production lines imported from Germany.

The name comes from the altitude of the glacier that feeds water to the factory, 5,100 m (16,700ft) above sea level.

The water is sold in China's far-off cities. The factory brings jobs and money to a poor region.

Around 150 Tibetans work here, among them Pubu Zhaxi.

He says the work is not hard and he earns 5,000 renminbi ($735, £491) a month, a handsome wage in Tibet.

But it is not all quite so simple.

The factory, it turns out, is owned by a company registered in Hong Kong, so the profits, and the water, really flow outside Tibet.

And although the factory's boss says collecting the run-off from the glacier has no environmental impact, the water would have flowed into a wetland in the valley where yak herds graze the mountain grasses.

Ancient structure

In Lhasa too there are signs of change all around.

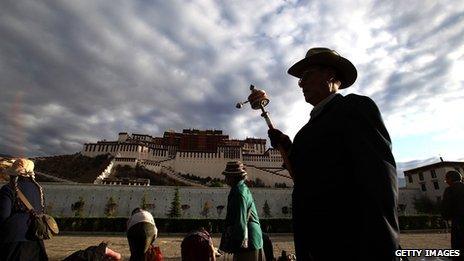

The Potala Palace, rising high above the city, was once home to the Dalai Lama before he fled into exile.

It is a symbol of the way, for centuries, Tibet resisted outside influence.

But now the palace courtyard is full of Chinese visitors. They pose in Tibetan cowboy hats. Tourism is another plank in China's plan for development.

Qiangba Gesang, the director of the Potala Palace says that four years ago 370,000 tourists were allowed to visit the palace each year.

Now the number has gone up to 600,000. It is a sign of the way China's economy is developing and of the way Tibetans are becoming richer too, he says.

But he is not so clear when asked if the surge in numbers is having any impact on the ancient structure.

Comfort?

The influx of Han Chinese as tourists and migrants is altering Tibet.

So too is China's policy of moving every Tibetan herder and farmer into a new home. We are taken to see one model project just outside Lhasa.

Neat rows of grey stone houses stand in lines with Tibetan prayer flags fluttering from them.

China says it has constructed 230,000 of what it calls these "comfort houses" for 1.3 million Tibetans in the past four years.

It gives grants to help pay the cost. But the Tibetans have to use their own savings too and take out loans, so they end up with debt.

And, we are told, many of the Tibetans in this village have leased their farmland to Chinese migrants to raise money.

The Chinese grow vegetables while the Tibetans now work on construction sites in Lhasa. So Tibet's demographics are shifting.

Backwardness

Inside one house we find Do Bu Jie.

Do Bu Jie lives in a newly built "comfort house"

In his seventies, he wears a brown Fedora hat at a jaunty angle.

On his wall, as in every house we see here, there is a poster of China's Communist leaders, from Mao Zedong to Hu Jintao. Below it is a huge television set.

Do Bu Jie is a Communist Party member and supporter of the housing project.

"Our old house was made out of mud, it wasn't this good," he said. "I was just a farmer. But the Communist Party looks after us."

China's government genuinely believes its policies are helping transform Tibet from what officials say was a state of "backwardness".

But while some Tibetans are benefiting, many are not convinced.

They believe the economic gains are largely flowing to Chinese immigrants.

And they say their way of life and their cultural identity are all under threat.

Railway boom

The number of Chinese moving to Tibet is a sensitive topic.

The railway station design echoes the Potala Palace

When I asked for figures from officials in Beijing before our trip I was given a stern lecture about the bias foreign journalists have in reporting on Tibet.

Then I was told the statistics are not kept.

But in Lhasa we were taken to the new railway station, a giant, modern building, echoing and empty. Its style vaguely echoes the Potala Palace.

The railway is Beijing's biggest investment in Tibet, costing billions of dollars, and is designed to connect the region with the rest of China.

A train pulls in and passengers fill the platform.

There are Chinese migrant workers, dragging sacks of possessions, Tibetans with bundles of goods, Chinese tour groups all wearing red caps, the tour-leader waving her flag, and a few foreign tourists too.

We are told 3,000 passengers come here everyday, so roughly one million a year, a third of them visitors.

In snatched conversations we managed with Tibetans during our five-day tour it was clear the sheer number of Han Chinese flowing in to Tibet was a cause of resentment.

Chinese vs Tibetan

Another sensitive topic is the survival of Tibetan as a language.

Tibetan children are taught a Chinese curriculum

At the Tibet Shanghai Experimental School, so-called because it is built with funds from the Shanghai government, a class full of Tibetan children in red and white track-suits are all having a Chinese lesson.

Nine hundred of the students here come from the families of farmers and herdsman, we are told. Many get help from the central government with funding to enjoy this education.

It is another showcase project.

But although the school says teaching Tibetan is a priority, on closer scrutiny, that does not seem to be the case.

Half the teachers are Chinese, and only Tibetan language is taught in Tibetan. No other subject is.

All the exams, except for Tibetan language, have to be written in Chinese.

Even the signs around the school and the names of the classrooms are all in Chinese.

And the curriculum is all Chinese too. So the children, we are told, are taught that the Dalai Lama is a threat to China.

It is clear China's drive for development is transforming Tibet, improving incomes and changing lives.

But it seems that is not always being welcomed.

For all the benefits China says it is bringing them, the impression left by our visit was that Beijing is struggling to win the consent of ordinary Tibetans.

And in a generation's time their homeland may have changed irrevocably.

- Published14 July 2010

- Published15 July 2010

- Published3 July 2010