Shadrake case highlights Singapore censorship battle

- Published

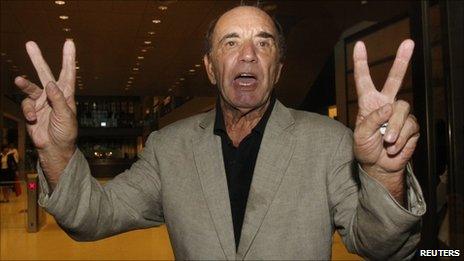

Author Alan Shadrake is accused of "scandalising the Singapore judiciary"

The title of Alan Shadrake's book leaves little room for doubt as to the tone of the content.

"Once A Jolly Hangman - Singapore Justice in the Dock" is a critique of the way the death penalty is applied in the city state. It alleges double standards and a lack of impartiality.

That has prompted Singapore's attorney general to charge the 75-year-old Briton with contempt, arguing that passages of the book "scandalise the Singapore judiciary" and "undermine the authority of the courts".

Mr Shadrake faces a possible jail sentence and a hefty fine if found guilty. He is also under investigation for criminal defamation.

Open defiance

The case has highlighted not just the use of capital punishment in Singapore, but also the broader issue of freedom of speech in a country where dissent is rare.

Human rights groups say the Singaporean authorities too often resort to the courts to silence their critics.

Alan Shadrake, however, shows no signs of staying quiet. He entered Singapore's High Court building for his first hearing holding up two fingers in a "V for victory" salute.

"Freedom and democracy for Singapore," he shouted, as he waited to walk through the security scanners.

Blog activist Seelan Palay has been sentenced to 12 days in jail for unlawful assembly

Singapore is not used to that kind of open defiance. This tiny state prides itself on being one of the most stable and prosperous nations in Asia.

Gleaming high-rise office blocks nestle with pristinely maintained colonial buildings.

Traffic flows freely. Healthcare is among the best in the world. The air is clean. In fact, everything is clean. Movies are censored. Littering is unheard of.

There is no doubt that, compared to many of their regional neighbours, Singaporeans enjoy a high standard of living.

But critics say there is a price to be paid. People are expected to conform.

It is as if there is an unspoken but clearly understood deal between citizen and state: the system will look after you, as long as you do not question it.

That system has largely been designed by Singapore's founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, and managed by the People's Action Party, the PAP, which has been in power since independence in 1965.

Lee Kuan Yew has formally handed over the premiership to his son, Lee Hsien Loong, but retains the title of "minister mentor".

The government declined the BBC's request for an interview. But Abner Koh was willing to talk. He is a member of the youth wing of the PAP. Over Chinese tea at a riverside restaurant, he made the case for strong leadership and clear rules.

"We have to bear in mind that Singapore is a multi-racial and multi-religious society," he said. "Certain forms of restriction are definitely necessary to ensure harmonious living amongst the different communities in Singapore.

'Speaking up'

But other young Singaporeans are beginning to question the status quo.

Seelan Palay is a blogger, film-maker and political activist. He has just started serving a 12-day prison sentence for unlawful assembly. But speaking before he began his sentence, he said he had no regrets.

"I think life in Singapore would be much better if people started speaking up and standing up for what they believe in," he said.

But doesn't the prospect of a jail term deter you, I asked? "No, it does not," Mr Palay replied without hesitation. "Many others have gone to prison for what they believe in before me. Some of them have been detained without trial for 20 years, 30 years.

"I'm only going to do a 12-day sentence. And I have 10 other open cases which I may also have to go to prison for, so I'd better get used to it."

Mr Palay is a staunch supporter of Alan Shadrake, even going so far as to post the author's bail. Mr Shadrake's case has now been adjourned to allow his defence more time to prepare.

The charges could possibly be dropped if he acceded to the prosecution's request for an apology. But there seems little chance of that.

"I didn't do this to chicken out and say sorry and grovel to them like most Singaporeans have to do, to live a normal life," he told me as he left the High Court.

And somehow it no longer feels like this is just Alan Shadrake's fight. He has become a proxy for Singapore's own internal battles.

- Published30 July 2010