How uninhabited islands soured China-Japan ties

- Published

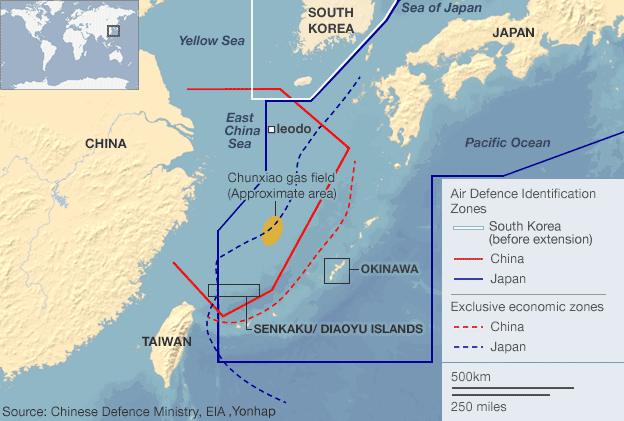

Ties between China and Japan have been strained by a territorial row over a group of islands, known as the Senkaku islands in Japan and the Diaoyu islands in China.

What is the row about?

At the heart of the dispute are eight uninhabited islands and rocks in the East China Sea. They have a total area of about 7 sq km and lie north-east of Taiwan, east of the Chinese mainland and south-west of Japan's southern-most prefecture, Okinawa. The islands are controlled by Japan.

They matter because they are close to important shipping lanes, offer rich fishing grounds and lie near potential oil and gas reserves. They are also in a strategically significant position, amid rising competition between the US and China for military primacy in the Asia-Pacific region.

What is Japan's claim?

Japan says it surveyed the islands for 10 years in the 19th Century and determined that they were uninhabited. On 14 January 1895 Japan erected a sovereignty marker and formally incorporated the islands into Japanese territory.

After World War Two, Japan renounced claims to a number of territories and islands including Taiwan in the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco. These islands, however, came under US trusteeship and were returned to Japan in 1971 under the Okinawa reversion deal.

Japan says China raised no objections to the San Francisco deal. And it says that it is only since the 1970s, when the issue of oil resources in the area emerged, that Chinese and Taiwanese authorities began pressing their claims.

The disputed East China Sea chain consists of five small islands and three rocks

What is China's claim?

China says that the islands have been part of its territory since ancient times, serving as important fishing grounds administered by the province of Taiwan.

Taiwan was ceded to Japan in the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, after the Sino-Japanese war.

When Taiwan was returned in the Treaty of San Francisco, China says the islands should have been returned too. Beijing says Taiwan's Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek did not raise the issue, even when the islands were named in the later Okinawa reversion deal, because he depended on the US for support.

Separately, Taiwan also claims the islands.

Why is the row so prominent now?

Activists from Japan, China and Taiwan have all tried to sail to the islands to make a political point

The dispute has rumbled relatively quietly for decades. But in April 2012, a fresh row ensued after outspoken right-wing Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara said he would use public money to buy the islands from their private Japanese owner.

The Japanese government then reached a deal to buy three of the islands from the owner in a move to block Mr Ishihara's more provocative plan.

But this angered China, triggering public and diplomatic protests. Since then, Chinese government ships have regularly sailed in and out of what Japan says are its territorial waters around the islands.

In November 2013, China also announced the creation of a new air-defence identification zone, which would require any aircraft in the zone - which covers the islands - to comply with rules laid down by Beijing.

Japan labelled the move a "unilateral escalation" and said it would ignore it, as did the US.

What is the role of the US?

The US says that the islands fall within its security treaty with Japan

The US and Japan forged a security alliance in the wake of World War II and formalised it in 1960. Under the deal, the US is given military bases in Japan in return for its promise to defend Japan in the event of an attack.

This means if conflict were to erupt between China and Japan, Japan would expect US military back-up. US President Barack Obama has confirmed that the security pact applies to the islands - but has also warned that escalation of the current row would harm all sides.

What next?

The Senkaku/Diaoyu issue highlights the more robust attitude China has been taking to its territorial claims in both the East China Sea and the South China Sea. It poses worrying questions about regional security as China's military modernises amid the US "pivot" to Asia.

In both China and Japan, meanwhile, the dispute ignites nationalist passions on both sides, putting pressure on politicians to appear tough and ultimately making any possible resolution even harder to find.

- Published14 September 2010

- Published12 September 2010

- Published8 September 2010