Anger simmers over Okinawa base burden

- Published

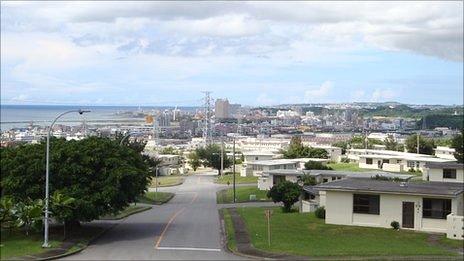

US military base in central Okinawa, with a residential area in the background

The Japanese island of Okinawa is the reluctant host of dozens of US military bases - and a row over moving an airfield has sparked an angry stand-off.

Shuri Castle stands on a hill above the Okinawan capital, Naha.

It used to be the seat of the Ryukyu kings, who ruled over an archipelago south of Japan and north of Taiwan.

It is an elegant red pavilion where the kings received emissaries and conducted trade across Asia.

Now the castle is a tourist attraction in Japan's southern-most prefecture. It looks down on densely-packed apartment blocks and offices.

Heading north from the castle, the roads are gridlocked. For 20km, almost without a break, US bases stand on one or other side of the road.

High fences with "Keep out" signs make it clear that these areas are off limits to Okinawans.

Opposite them bars and shops sell used cars and Mexican food. Cargo planes and fighter jets fly overhead.

The bases occupy almost a fifth of the island. They constitute 74% of all US bases in Japan, on less than 1% of its landmass.

Okinawans have been saying for decades that this is not fair. And in April 90,000 residents gathered to protest, in the biggest show of opposition for 15 years.

"Okinawans understand there are national security needs, but they do not understand why Okinawa has to have such a large proportion of the US bases," says Naoya Iju of the prefectural government's Military Base Affairs Division.

"Many people think: 'We are all Japanese so why do just Okinawans have to bear this burden?"

Crowded island

Okinawa was forcibly incorporated into Japan in the late 19th Century. Sho Tai, the last Ryukyu king and master of Shuri Castle, died in Tokyo in 1901. A process of Japanisation began.

After the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II, Tokyo ceded Okinawa to temporary US control.

The US seized land for bases which now serve as the foundation for the US-Japan security alliance. Simply put, the US will protect Japan if Japan hosts and pays for its troops.

Today 26,500 US military personnel are in Okinawa, on more than 30 different bases.

These include the huge air base at Kadena and a massive jungle training area in the north. Plus, of course, Futenma, the Marine Corps airbase right in the middle of Ginowan city, where houses and schools nestle right up against the fence.

Both the Japanese and US governments say they are vital for maintaining security in an unstable and increasingly competitive region.

Supporters say there are benefits. Okinawa is Japan's poorest prefecture and base-related income provides about 5% of its income.

More than 9,000 residents are employed by the bases. Generous rents are paid to families whose land is used, as are subsidies to local authorities hosting bases.

But opponents point to aircraft noise and traffic disruption - they have to drive around the bases. They complain about high levels of base-related crime. They say Okinawans - who have the highest birth-rate in Japan - desperately need the land back to live on.

They also argue that the bases are eroding Okinawa's cultural identity and the subsidies creating a dependency culture. They say that if the base land were returned, it could be made more economically productive.

False hope

Protest over the issue has gone in waves. One came in 1972, when Okinawans found that reversion from US to Japan rule did not result in base closures.

Another came in 1995 after the gang-rape of a 12-year-old girl by three US troops.

The latest wave was triggered by Yukio Hatoyama, elected prime minister in June 2009, who suggested Futenma airbase could be moved off Okinawa altogether, instead of to the north of the island as previously agreed.

"Until then no politician had suggested moving the base out of Okinawa," said Susumu Inamine, the mayor of Nago, the northern city proposed as the relocation site. "The fact that the DPJ [Democratic Party of Japan] said it could gave people hope."

Amid this wave of hope, Okinawans elected four anti-base MPs to the national parliament. That same wave, in January, helped Mr Inamine fight the Nago mayoral election on an anti-base platform and win.

The huge April rally was held. The Okinawan prefectural assembly unanimously backed a letter demanding the removal of the base off the island. Seventeen thousand people formed a human chain around Futenma.

But - after intense US pressure - Mr Hatoyama back-tracked. In May he said he had been unable to find an alternative site for the base. His "heart-breaking conclusion" therefore, was that the relocation should go ahead as planned. Then he stepped down.

Okinawans were furious. Local media described it as a betrayal. Why, people asked, was it more acceptable to put bases in Okinawa than anywhere else in the country?

Since then, the anger has not gone away. Cars and buses sport signs calling for a "peaceful" Okinawa. So do some buildings. Local media remain militant.

'Discrimination'

Professor Tetsumi Takara, Dean of the Graduate School of Law at Ryukyu University, says the issue is much bigger than just the relocation plan.

Prof Tetsumi Takara says Okinawans are waiting for the governor's election to make their anger felt

Okinawans feel that their voices have been ignored by the Japanese government for decades, he says.

Since becoming part of Japan they have had no control over their fate - during World War II, when Okinawa was the site of Japan's only land battle, in the 1960s when US nuclear weapons were located in Okinawa, in 1972 when US rule ended but the bases stayed.

The rights of Okinawans, he says, have been consistently subordinated to Japanese security concerns. "Okinawans are being discriminated against. That is the fundamental problem," he says.

He says this point is not adequately understood on the mainland.

"When we protested in April, they thought we were protesting about the US military but that wasn't it," he said. "It was more about the questionable treatment we are getting from the Japanese government."

Naoya Iju, of the prefectural government, says that many people think that Okinawans are being treated as second-class citizens.

Mr Hatoyama's flip-flop even appears to have engaged young people, who have only ever known Okinawa with the bases.

"My mother worked on a base and I learned English because of the bases," said one young civil servant. "But now more and more people are starting to think that there is something wrong here."

The relocation plan that sparked the wave of protest is currently stalled pending the Okinawa governor's election in November.

It is the governor who can grant or deny permission for the plan to go ahead - and the staunchly anti-base mayor of Ginowan, Yoichi Iha, is challenging an incumbent whose view on the relocation plan remains ambiguous.

An Iha victory could force the Japanese government to choose between over-ruling its own citizens and their democratically-elected representative or jeopardising its key security relationship.

Okinawans, says Prof Takara, do not protest on the streets every day. But they watch and they wait and many, he says, are looking to the election as a chance to make their feelings felt.

- Published23 June 2010

- Published2 June 2010

- Published30 May 2010