Exposing the world of Japan's yakuza mafia

- Published

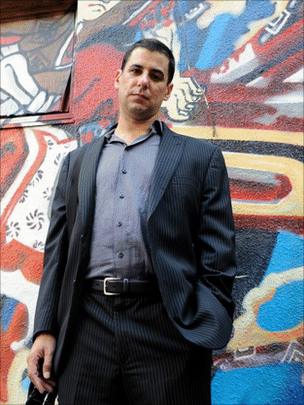

Jake Adelstein's work took him inside Tokyo's seedy - and dangerous - sex industry

"Erase the story… or we'll erase you. And maybe your family. But we'll do them first so you learn your lesson before you die."

It was the warning that ended it all.

Twelve years of reporting on the terrifying world of the yakuza - the Japanese mafia - and Jake Adelstein's luck had finally run out.

He had been working on a story which involved one of Japan's most feared and violent mobsters, and as he sat before a softly spoken enforcer from the notorious Goto-gumi gang, he decided no story was worth his family.

"All your personal information, your phone number, your phone records, where you live, the people you're close to... everything that we know, he knows as well," the police had explained to him.

"You need to really think about who your friends are and who you're in contact with the most and warn them."

Five years on, Adelstein only now feels it is safe to talk about working for Japan's biggest newspaper, Yomiuri Shimbun, in his book Tokyo Vice.

Disorganised crime

Jewish-American Adelstein was arguably an unlikely candidate for a job that involved getting close to hardened criminals.

As a college student, he left Missouri to study Japanese literature at Sophia University. It was a chance, he thought, to learn more about martial arts and Buddhism.

But as he neared the end of his course, he decided to apply to be a journalist.

Unlike most countries, where traditionally a reporter will rise through the ranks of local press before embarking on a national title, employment at Yomiuri Shimbun - with its circulation of 15 million, the largest in the world - came by way of an entrance exam.

"I was very surprised that the Yomiuri Shimbun even accepted me for the interview," Adelstein told the BBC World Service.

"But actually my test scores were comparable, or better, than many of my Japanese colleagues - probably because I'd been preparing so long."

He got the job, and began working, as most newcomers do, as a crime reporter.

Compared with his home country, the crime scene here was very different - in Japan, organised crime has not been driven underground.

"There is an idea within Japan that the yakuza are a necessary evil, that by having them around they keep street crime down," Adelstein explained.

"And the other idea is that the only thing worse than organised crime is disorganised crime."

This approach allows the yakuza a curious freedom; they run their "business" from offices well-known to locals as well as police.

Adelstein can vividly remember a visit to one such office for his first meeting with a yakuza boss - a man described by his police contacts as a "total gentleman" and nicknamed The Cat.

"We sit down. He offers me a cup of green tea and I refuse. I say no, thank you. He's immediately offended."

The Cat - known officially as Kaneko - was not being unusually touchy about his guest's dislike of green tea.

A rival gang leader - who wanted The Cat's job - had begun rumours about police bribery.

Keen to distance themselves from accusations of being paid by the yakuza, police officers began to refuse green tea and other pleasantries when visiting Kaneko's offices.

But The Cat worried this looked like a bluff, and that soon his own people would begin to believe he was a police informant.

The Cat called in "dependable" Adelstein to put across his story.

He did. The Cat's rival was never heard from again.

"I didn't really see that coming," Adelstein says.

"I was very naive. It certainly wasn't my intention to get someone bumped off. But that's how it worked out and it's not like I could change it."

Human trafficking

Adelstein says he has held back some information in his book - both about his sources and his own actions in getting stories.

He admits sleeping with the mistress of a mob boss, but stops short of going into detail about the nature of some of his work, including as a "masseuse".

Many yakuza members are covered with tattoos pledging their allegiance

His willingness to bury himself in a story helped him gain the trust he needed from vulnerable sources in the case of Lucie Blackman, the 21-year-old British Airways worker who made headlines across the world after being murdered at the hands of "businessman" Joji Obara.

As a Western reporter with experience of the local area, Adelstein's insights were invaluable - particularly to Ms Blackman's father, whom he spoke with on a regular basis, eventually breaking to him the news of his daughter's death.

Covering the story revealed the dark secrets of Tokyo's sex industry.

"I think I was on my best behaviour until I started covering the human trafficking issues. And then things become very different."

One anonymous source - a prostitute - went missing after helping Adelstein on a story, and later he heard that she had been raped, tortured and killed.

"I asked her to look into one group that was running in Roppongi," he remembers.

"She got back to me and told me it was an organisation run by Goto-gumi.

"I asked her to stop looking, and quit immediately. She didn't listen to me. The next time I tried to contact her, I couldn't...

"That was a very bad judgement call."

Broken family

Graphic descriptions of gathering information in exchange for sexual favours make uncomfortable reading for Adelstein's wife.

"Sometimes after reading the book she's supportive and understanding," Adelstein says.

"But you know, I think our marriage is irreparably damaged. I wouldn't expect her to stay married to me. I wouldn't want to be married to me."

However, he does hope that his children will read his book when they are older.

"I want my kids to understand why I did the things I did, and why we had to move to the United States. I don't want them to repeat the same mistakes I made.

"They may be angry, they may be understanding - but at least they'll know who I am and what I did."

- Published23 September 2010