North Korea's nuclear programme: How advanced is it?

- Published

Negotiations over North Korea's nuclear programme, including the Yongbyon nuclear plant shown, have been a stop-start process

North Korea's nuclear programme remains a source of deep concern for the international community. Despite multiple efforts to curtail it, Pyongyang says it has conducted five nuclear tests.

Has North Korea got the bomb?

Pyongyang used a three-stage rocket to put a satellite into space in 2012

Technically yes - North Korea has conducted several tests with nuclear bombs.

However, in order to launch a nuclear attack on its neighbours, it needs to be able to make a nuclear warhead small enough to fit on to a missile.

While North Korea claims it has successfully "miniaturised" nuclear warheads, international experts have long cast doubt on these claims.

Yet according to information leaked to the Washington Post, external in August 2017, US intelligence officials now do believe North Korea is capable of miniaturisation.

How powerful are North Korea's nuclear bombs?

North Korea says it has conducted five successful nuclear tests: in 2006, 2009, 2013 and in January and September 2016.

The yield of the bombs appears to have increased.

September 2016's test has indicated a device with an explosive yield of between 10 and 30 kilotonnes - which, if confirmed, would make it the North's strongest nuclear test ever.

The other big question is whether the devices being tested are atomic bombs, or hydrogen bombs, which are more powerful.

H-bombs use fusion - the merging of atoms - to unleash massive amounts of energy, whereas atomic bombs use nuclear fission, or the splitting of atoms.

The 2006, 2009 and 2013 tests were all atomic bomb tests.

North Korea claimed that its January 2016 test was of a hydrogen bomb.

But experts cast doubt on the claim given the size of the explosion registered.

Plutonium or uranium?

Another question is what the starting material for the nuclear tests is.

Analysts believe the first two tests used plutonium, but whether the North used plutonium or uranium as the starting material for the 2013 test is unclear.

A successful uranium test would mark a significant leap forward in North Korea's nuclear programme. The North's plutonium stocks are finite, but if it could enrich uranium it could build up a nuclear stockpile.

Plutonium enrichment also has to happen in large, easy-to-spot facilities, whereas uranium enrichment can more easily be carried out in secrecy.

Can North Korea deliver it?

There is no consensus on exactly where North Korea is in terms of miniaturising a nuclear device so that it can be delivered via a missile.

According to that information leaked to the Washington Post, external, US intelligence officials now believe North Korea's claim that it has the technology to fit its missiles with nuclear warheads.

Japan's defence ministry has also recently stated this is a possibility.

The new assessment comes only weeks after North Korea tested what it said was an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of reaching the US mainland. While analysts doubt Pyongyang's claim, most experts agree the missile could reach Alaska or Hawaii.

What else do we know about the North's nuclear programme?

North Korea's nuclear actions have become a cause of concern among its neighbours, especially South Korea

A site in the mountains near Yongbyon, north of Pyongyang, is thought to be the North's main nuclear facility, while the January and September 2016 tests were said to have been carried out at the Punggye-ri site.

The Yongbyon site processes spent fuel from power stations and has been the source of plutonium for North Korea's nuclear weapons programme.

Both the US and South Korea have also said that they believe the North has additional sites linked to a uranium-enrichment programme. The country has plentiful reserves of uranium ore.

What has the global community done about this?

The US and North Korea aimed at restarting denuclearisation talks before Kim Jong-il, right, died

The US, Russia, China, Japan and South Korea engaged the North in multiple rounds of negotiations known as six-party talks.

There were various attempts to agree disarmament deals with North Korea, but none of this has ultimately deterred Pyongyang.

In 2005, North Korea agreed to a landmark deal to give up its nuclear ambitions in return for economic aid and political concessions. In 2008, it destroyed the cooling tower at Yongbyon as part of the disarmament-for-aid deal.

But implementing the deal proved difficult and talks stalled in 2009.

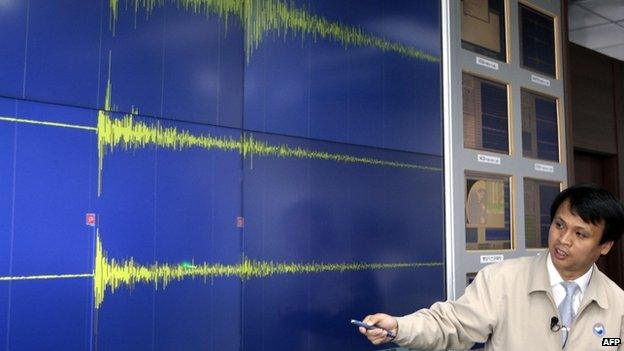

North Korea carried a nuclear test in 2009, which resulted in seismic waves shown here in Seoul

The US never believed Pyongyang was fully disclosing all of its nuclear facilities - a suspicion bolstered when North Korea unveiled a uranium enrichment facility at Yongbyon, purportedly for electricity generation, to US scientist Siegfried Hecker, external in 2010.

In 2012, North Korea suddenly announced it would suspend nuclear activities and place a moratorium on missile tests in exchange for US food aid. But this came to nothing when Pyongyang tried to launch a rocket in April that year.

The United Nations has tightened sanctions against North Korea following nuclear tests

In March 2013, after a war of words with the US and with new UN sanctions over the North's third nuclear test, Pyongyang vowed to restart all facilities at Yongbyon. By 2015, normal operations there appeared to have resumed.

The 2016 tests brought international condemnation, including from China - the North's main trading partner, and only ally.

In 2017, the UN agreed a new sanctions package in response to the tests.

In August, US President Donald Trump threatened North Korea with "fire and fury" should the country not abandon its threats against the US.

The rhetoric from Washington failed, though, to rein in Pyongyang which in turn said it was developing a strike plan to hit the US territory of Guam, an island in the Western Pacific.