China: How much freedom do its people have?

- Published

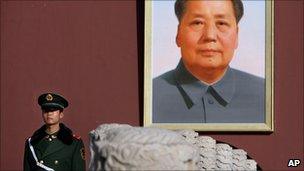

Freedoms have expanded since the days of Mao Zedong and his grey suit

The ceremony for this year's Nobel Peace Prize - awarded to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo - will be held on Friday. The prize has re-ignited debate about China's political system and about how much freedom its people have. Michael Bristow reports from Beijing.

In an upmarket shopping complex in central Beijing, a newly-opened boutique is selling clothes made by some of China's top fashion designers.

There are a wide range of items on sale; mini-skirts, knitted sweaters and T-shirts with slogans printed on the front.

Not more than a generation ago most Chinese people wore the same few styles, clothes made in three or four drab colours.

In clothing at least, Chinese people can today express themselves freely.

People's control over their own lives has been enhanced in many other ways, as the government has reformed the economy and withdrawn from many areas of society.

Citizens can now start their own businesses, buy their own homes and travel abroad freely.

But in one respect there has been little change. Politics is still completely controlled by the Chinese Communist Party, which tolerates little criticism.

Dress code

Chinese people have regained a great deal of control over their lives since the former leader Deng Xiaoping initiated economic reforms in 1979.

Ms Hong says Chinese society has changed radically in the last 30 years

Hong Huang, the woman behind the Beijing boutique, said that wearing the wrong kind of clothes could once have got you into trouble.

To explain, she held up one of the items on sale in her shop, a grey sweater with a black tutu attached to it.

"Anybody who wore this just 30 years ago would be seen as someone who'd just escaped from the insane asylum - or someone who belongs there," said Ms Hong, whose shop is called Brand New China.

Worse still, it could have got you into trouble with the authorities, she said.

Many Chinese people at the time stuck to wearing what is known in the West as the "Mao suit", named after the Chinese revolutionary leader who made it famous.

The Cultural Revolution, begun by Mao Zedong in 1966, marks perhaps the high-point of communist fervour in China.

Capitalism was a dirty word - and anyone supporting it could be sent to prison. But all that has now changed.

"It's inconceivable that 20 or 30 years ago I'd be able to open a store in the middle of the city playing Christmas music and selling Chinese designs of mini-skirts, leggings and earrings," said Ms Hong, who also publishes a fashion magazine called iLook.

'Sabotage'

Politics though is one area that remains out of bounds for most Chinese people. Officials have little time for anyone who challenges their authority.

When he announced Liu Xiaobo had won this year's award, the chairman of the Nobel Peace Prize committee, Thorbjorn Jagland, noted that China's constitution promised certain rights, including freedom of speech.

But he added: "In practice, these freedoms have proved to be distinctly curtailed for China's citizens."

China defends its current political system, saying that it maintains stability, which allows the economy to develop and helps people get wealthier.

Officials believe Mr Liu's suggestions for political reform, outlined in the document Charter 08, threaten the achievements of the last three decades of reform.

"Liu Xiaobo did everything possible to sabotage China's development and stability," reads a note from the Chinese embassy in Norway to foreign diplomats.

That note appears to urge those diplomats not to attend Friday's Nobel Peace Prize ceremony.

The result of this approach is a "police state", according to the artist and government critic Ai Weiwei.

"People can be monitored, their phones can be tapped and you can be followed. They can find you, they can intimidate you or scare you - or wrongly accuse you," he added.

Red line

There are people, like Liu Xiaobo, that seek to push the political boundaries.

Even at the shop Brand New China there are clothes on sale by designers who have tried to add a touch of politics to their work.

One has a collection of clothes that features pandas - not cuddly images often used by the government to represent the country, but angry and unhappy bears.

Social commentary or high fashion?

The problem for anyone getting involved in politics in China, according to Hong Huang, is that you never know how far you can go.

"I think every country has a line that you cannot cross. The problem in China is that that line is a moving target," she said.

"There are times when you think the line has moved far away, but the next thing you know, you are standing right on it."