Growing hunger for Chinese art

- Published

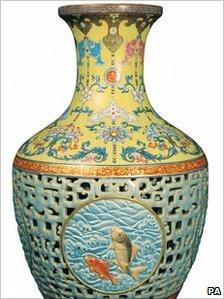

The vase sold in London is thought to have left China about 150 years ago

An 18th Century Chinese vase is bought by a Chinese buyer at a small suburban auction house in London for £43m ($66m), more than £53m after fees and commission.

The sale price is 40 times the pre-sale estimate.

In Hong Kong a local buyer pays nearly $17m for a pair of 5ft-high enamel cranes - believed to be a gift from an 18th Century Chinese emperor to his son.

Another Hong Kong-based collector pays $32m for an 18th Century Chinese floral vase.

Last year, the hugely inflated sums of money being paid for Chinese art and artefacts made headlines regularly.

But what has been pushing prices so high?

Trade insiders say the recovery from the world economic crisis brought an influx of new, wealthy bidders into the auction houses.

Zhang Lifan, a historian, is the son of Zhang Naiqi, China's first Minister of Food and one of the most respected collectors of Chinese artefacts in his time.

His father's collection was confiscated by the government during the Cultural Revolution.

Mr Zhang believes many of the bidders at the moment for Chinese artefacts in Hong Kong, London and elsewhere are investors, not collectors.

"Some are the new rich, trying to buy artefacts to show off how wealthy they are," he says.

"A few of them could be nationalists, trying to buy items overseas to bring them back to China, but they are in a minority."

Culture v capital

Some collectors are dismissive of these interlopers with deep pockets.

Ma Weidu is the host of one of China's most popular television programmes about ancient art collection.

Zhang Lifan says many of the bidders at the moment for Chinese artefacts are investors, not collectors

"Most of the highest prices are paid for second-rate items," he says. "It takes time to cultivate aesthetic judgement."

Auctions of artefacts in China only really began 15 years ago.

In the last five years they have taken off, but it is not a large market.

There are not nearly as many artefacts from China as there are from the West, partly because so many were lost or broken in the turmoil of the country's troubled past, says Mr Ma, himself a collector.

"That's why when new money comes in, it feels very crowded."

He complains that the collectors used to be the intellectuals, "the elite" as he describes them.

Nowadays, it is the rich who are collecting, some of whom "can't even read the script on the paintings," he says, "but they still buy them".

It is no longer about culture but capital. "It's like a war," he says, "whoever has the the bigger gun is in a stronger position."

The big auction houses like Christie's counter that buyers can get good advice from their experts before making any purchase.

There is still a big price gap between iconic Western art and iconic Asian pieces, and although it is closing, there is still room for prices to rise further.

Jonathan Stone, the Hong Kong-based Asia Managing Director of Christie's, says the proportion of buyers there for Asian art this season from mainland China rose from 40% in 2009 to 51% this year.

But the whole market's value increased significantly, so the value of the sales by customers from the mainland was 250% higher than the year before.

"I think there is a genuine passion and enthusiasm in China for buying back their own culture, which has been dispersed through the world for hundreds of years," he says.

"But it's not just Chinese people, people in greater China or people of Chinese heritage. At the very top level, there is very great enthusiasm indeed in the West for great Chinese works of art as well."

Government role

It is hard to be certain about the extent of the Chinese government's involvement in the repatriation of works of Chinese art.

China set up a "Precious Relics Rescue Fund" nine years ago, but the sums available to it "are so small it can hardly do anything really", says Qin Jie, an official from the China Collectors' Association.

Some suspect that the government does have a hand in some of the recovery of precious pieces, but it is more covert.

One of the mainland's fastest growing auction houses is Beijing Poly Auction Company, established five years ago.

China tried but failed to stop the sale of two bronze statues from the Summer Palace at auction in Paris

Its parent company is the Poly Group, a state-owned enterprise (SOE) founded with the approval of the Central Military Committee and supervised by the People's Liberation Army until it became an SOE.

The Poly Group has salvaged four "national treasures" since 2000, the auction house says on its website - the heads of a cow, a pig, a tiger and a monkey which were lost from the Summer Palace in Beijing at the height of the second Opium War in 1860.

They come from a bronze water clock which showed the 12 figures of the Chinese zodiac.

But according to Zhang Lifan: "In fact, what the government wants to do is not buy artefacts back, but demand that they are returned."

Qin Jie, a collector of ancient books, has a few favourites he would like to see back on Chinese soil.

"One item I'd like to see returned is one of China's first copies of the Buddhist book, The Diamond Sutra," he says.

It sits in the British Museum in London.

Most of those artefacts that do find their way back into China go into private collections, not museums. But that is not to say, of course, that they might not be lent or donated to public institutions in the years ahead.

"When Asian people get rich, they start to care about their history," says Qin Jie.

"They want to enrich their lives with historical art."

He believes 30,000 artefacts will have come back to China in the last 12 months, a third more than were coming back five years ago.

No matter what role the government is playing behind the scenes - whether overt or covert, or even none at all, Mr Stone of Christie's says one thing is certain, the return of so much lost ancient art "won't displease them".

- Published22 November 2010

- Published12 November 2010

- Published19 October 2010