New Zealand earthquake: Depth and location key

- Published

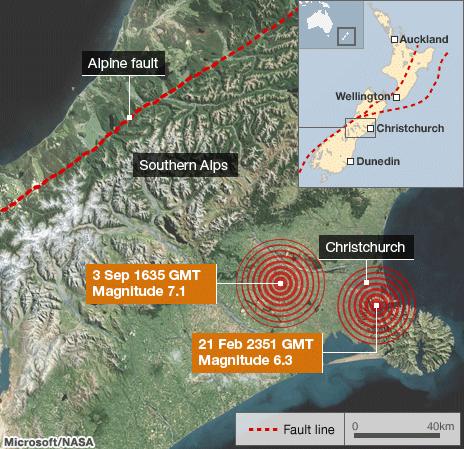

New Zealand sits astride a major plate boundary. Tuesday's quake was less energetic but more destructive than September's

It is in the nature of earthquakes that they tend to cluster in space and time.

And Tuesday's damaging tremor in Christchurch is almost certainly related to the much more energetic event that hit the region last September.

But whereas last year's quake caused much less damage and no deaths, the natural disaster that struck the city on 22 February looks set to go down in the record books as one of the most catastrophic in New Zealand's history.

The critical difference on this occasion is that the ground broke almost directly under the country's second city, and at shallow depth.

Christchurch would have been subjected to intense shaking. Buildings weakened last year would have crumbled this time; masonry collapse was widespread, even in a city where earthquake building regulations are among the strictest in the world.

Seismologists began to record the biggest tremor, a magnitude 6.3, on their equipment at 12:51 and 43 seconds local time (23:51:43 GMT) - right in the middle of Christchurch's day.

The epicentre, the point on the Earth's surface directly above where the rocks first rupture, was 10km southeast of the city. The focus, the point of rupture in the Earth itself, was a mere 5km down.

Contrast this with 3 September's magnitude 7.1 event; its epicentre occurred some 40km west of the city around Darfield and at a depth of 10km, and that event continued to rupture mainly away from the major built-up areas.

So although Darfield was something like sixteen times more energetic than Tuesday's tremor, the latter quake's effects would have been much more keenly felt in Christchurch this time.

"There are three different places where we've recorded the acceleration of the ground being larger than that due to gravity - so the ground would actually have felt like it was moving faster than if an apple fell out of a tree," Dr Bill Fry from the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences in Wellington, told the BBC.

There have been a series of aftershocks following on from September's event - approximately 10 that have been greater than or equal to magnitude 5.

"The September earthquake generated thousands of earthquakes that have continued since that time," explained Dr John Townend from the Victoria University of Wellington.

"They had been abating slightly; the number of earthquakes per day had diminished and in the last few days we were having only one or two a day or even none. But it is still possible to have big earthquakes in the tail-end of an aftershock sequence and unfortunately this appears to be one of those earthquakes."

The grander geological setting for both events is certainly the same.

New Zealand lies on the notorious Ring of Fire, the line of frequent quakes and volcanic eruptions that circles virtually the entire Pacific rim.

More specifically New Zealand straddles the boundary between two tectonic plates - the Pacific and Australian plates.

In the north of New Zealand, to the east of North Island, the more dense Pacific Ocean plate is pulled down beneath the lighter Australian plate in a process known as subduction.

To the south of South Island something similar is happening but the other way - the Australian plate is being forced below the Pacific plate.

On South Island itself, the location of the latest quake, a third scenario plays out. Here the plates rub past each other horizontally. This is most evident to geologists as the Alpine Fault that runs down the western spine of the land mass.

It is these plate movements which drive the volcanoes and earthquakes throughout New Zealand.

Dr Gary Gibson, from the University of Melbourne, Australia, commented: "On average, large earthquakes will occur less frequently in Christchurch than along the plate boundary, as has been the case for the last 200 years.

"However all earthquakes in the Christchurch region will be shallow, so the effect of a given earthquake will be worse than from a deeper plate boundary earthquake of the same magnitude."

A series of aftershocks continued to rattle the region on Tuesday. In the seven hours following the 6.3 tremor, there were four events that registered magnitude 5.0 or greater.

"Regrettably, this earthquake is likely to trigger aftershocks of its own and while they'll probably be of smaller magnitude, they will nevertheless continue for days and weeks or even longer," said Dr Townend.

"Unfortunately, this earthquake has served really to re-energise the earthquake activity surrounding the people of Christchurch; and it comes on the back of a large number of other earthquakes, so buildings have been structurally weakened and the population is that much more fraught as well."

The events of recent months have stimulated a lot of thought and research.

Scientists may be witnessing the consequences of blind fault activity - that is, activity on faults that does not have obvious expression at the surface because previous tremors happened so long ago the evidence for them has since eroded away.

Dr Roger Musson from the British Geological Survey observed: "What we're seeing is a network of faults that people didn't know existed previously, because these are old faults.

"They haven't been active for perhaps tens of thousands of years and now they're suddenly leaping in to life. It's because these faults haven't been seen before that people didn't realise that Christchurch had quite the earthquake hazard problem that it turns out to have," he told BBC News.

- Published22 February 2011

- Published22 February 2011

- Published22 February 2011

- Published26 December 2010

- Published8 September 2010