How Japan tackles its quake challenge

- Published

Geological instabilities cause around 1,000 tremors each year

Japan gave the word tsunami - meaning harbour wave - to the world; the destructive sea surges have been recorded throughout the country's history.

Tsunamis are triggered by earthquakes, hundreds of which strike Japan each year.

An offshore quake in 1707 is said to have caused a tsunami that hit the island of Shikoku, leaving several thousand people dead.

Further back, in the 15th century, a giant wave is said to have swept away a hill-top hall housing the Daibutsu, a huge bronze Buddha, in Kamakura, a town south of Tokyo.

Japan is perched on top of several converging tectonic plates. Geological instabilities cause around 1,000 tremors each year.

Many of the small ones go undetected by the public, and residents are used to taking medium-sized quakes in their stride.

Some earthquakes, however, are etched in the national consciousness.

A powerful earthquake devastated the Japanese city of Kobe in 1995

In 1923 a huge earthquake struck Tokyo. Known as the Great Kanto Earthquake, the 7.9 magnitude tremor and subsequent fires that blazed through wooden houses killed around 100,000 people.

Seventy-two years later, another powerful 7.3 magnitude quake hit the port city of Kobe in western Japan.

Highways were toppled and thousands of buildings damaged. Some 6,400 people were killed and more than 400,000 injured; fires blazed across the city.

Seismic stations

It is widely thought that Tokyo is expecting another powerful quake - and that this quake is now overdue.

So Japan puts considerable effort into preparing its response systems, its infrastructure and its citizens for potential disasters.

The government has invested heavily in monitoring systems. Founded in 1952, the Tsunami Warning Service is operated by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA).

It monitors activity from six regional centres, assessing information sent by seismic stations both on and off-shore known collectively as the Earthquake and Tsunami Observation System.

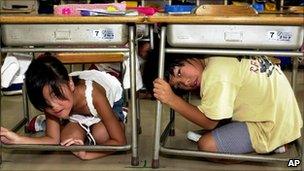

Earthquake preparedness is drilled into Japanese children during their school years

Using this system, JMA aims to send out a tsunami warning within three minutes of an earthquake striking.

When a quake hits, data concerning the magnitude and location are immediately flashed up on television by national broadcaster NHK.

The message then adds whether a tsunami warning has been issued and if so, for which areas.

In most towns and cities, loudspeaker systems can broadcast emergency information to residents.

In some rural areas, residents also have radios distributed by the local government over which instructions to evacuate can be broadcast.

Children practise ducking under the desk in earthquake drills throughout their school years. All adults are told where their closest evacuation centre - a park or sports field, for example - is located.

Tsunami shelters

Infrastructural checks are also in place. High-rise buildings in major cities are designed so that they sway rather than shake during earthquakes, making them safer.

In the wake of the Kobe earthquake, new regulations for quake-proofing buildings came into force, and some local governments offer citizens a structural health check on their homes.

Some coastal areas have tsunami shelters, while others have built floodgates to withstand inflows of water from tsunamis.

And if an earthquake above a certain magnitude strikes, the bullet train will stop and nuclear and other plants will automatically go into temporary shut down.

All in all, Japan is widely acknowledged to be one of the most earthquake-prepared nations.

But for all these safeguards, the risks posed are severe, as the latest massive earthquake has shown.