Japan quake: Aid worker's diary

- Published

Kathy Mueller is working for the International Federation of Red Cross (IFRC) in Japan, which was hit by a devastating earthquake and tsunami on 11 March. This is her account.

Going Home

It has now been more than a month since the tsunami and earthquake devastated the north-east coast of Japan. I have been here supporting the Japanese Red Cross Society and their communication needs for much of that time. But now it is time for me to go back to Pakistan where I am normally based.

Here in Japan, I have met many wonderful people; both those who are helping the thousands of people who continue to live in evacuation centres and the tsunami survivors themselves.

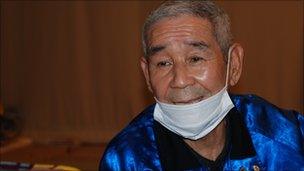

Yoshii Suzuki was swept out to sea by the wave and then returned by another

I recall 73-year-old Yoshii Suzuki, who very vividly told me about how the first tsunami wave swept him out to sea and, as he struggled to come up for air, how the second wave brought him back and plunked him on top of a house. He's a fisherman who says this wasn't the first time he's had to escape from the water, but it was definitely the most frightening.

And Koya, a precocious 8-year-old boy who told me it was hard to sleep at the evacuation centre in Somo city because there were so many old men who snored; he told them to stop and they did, so now he can sleep. He wants to move to a prefabricated house, but only if his friends are there. He says he wants to be a master sushi chef or a car racer so he can earn lots of money and buy a new house to replace his old home, which was lost to the waves.

There was Kamie Yamada, an elementary school teacher in Rikuzentakata who brought her students to safety in the higher hills. On the way there, she found an old disabled woman who was unable to walk, and carried her on her back to safety.

And then there was the Matsuhashi family, who now live in a 360-year-old shrine which somehow survived the tsunami when everything around it fell. They are kind and generous, warm and giving. Seven-year-old Masayuki showed me how to make paper airplanes. His 12-year-old sister Mizuki made me an origami crane. We have promised to write to each other once the internet is restored. Mizuki will ask her English teacher to translate. I will call on my Japanese friends to help me understand her words.

And I cannot forget Kuniko Kido, a 37-year-old nurse with the Japanese Red Cross Society. How she broke into tears when telling me about how she tries to form a bond with the evacuees to help them get through the trauma of what they have lived through is something I will never forget.

In my mind, I carry memories of the sights, the smells and the sounds. The sights of complete and utter devastation in many communities; of a stuffed Winnie the Pooh, standing guard outside a damaged shop in Otsuchi. The smell of smoke from fires that had been extinguished two weeks prior, of stagnant air smelling like sour milk in crowded evacuation centres. The sounds of babies crying and children laughing and playing.

Spring has arrived in Japan; the cherry blossoms have bloomed, normally a symbol of joy. Perhaps this year the blossoms will also bring with them renewed hope for the future.

Day Eleven

For those in shelters a return to normal life is more pressing than nuclear fears

It is a sensitive subject, one that I am not sure if I should raise when I meet survivors of the tsunami who now spend their days camped out in evacuation centres.

But the media is paying so much attention to it I feel I have a responsibility to ask about if those most affected by the 11 March double disaster are as concerned about the threat of nuclear contamination as reporters are.

I visit the Red Cross hospital in Ishinomaki. Staff tell me they keep abreast of developments and check radiation levels every day. They have been trained in what to do following a nuclear event, but as yet they have not treated anyone for high levels of radiation. Not one patient has asked about it.

I visit one evacuation centre after another and wait for someone to bring up the topic; no one does. Even in Fukushima prefecture, which is home to the now famously troubled nuclear plant, when asked, tsunami survivors are more worried about when they'll be able to move out of the evacuation centres and return home.

This is what is stressing them, their inability to live a normal life, not that radiation levels are higher than normal.

Red Cross medical staff say living in large evacuation centres is far from ideal. The food portions, while sufficient, are not quite as nutritious or enjoyable as a home-cooked meal. There is no privacy. In some centres, there is little or no heat. There is no family atmosphere.

"I just want my home back," cries one woman. Here on the ground, it is clear what their priorities are.

Day Ten

A teddy bear covered in mud, broken tea cups, family photo albums filled with moments captured of happier times. All very personal reminders that hundreds of thousands of people had their lives forever changed on 11 March 2011.

Residents in quake-hit towns say they want a return to normal life

I purposely look for these personal touches while climbing through the debris left behind by the tsunami. The story of the disaster in Japan is more than just burned buildings, houses ripped from their foundations, twisted metal or nuclear risks. We must remember that hundreds of thousands of mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, grandmothers and grandfathers are now living what is easier to imagine as the set of a Hollywood movie.

"I just want my town back. I just want my life back," cries one woman softly in an evacuation centre in Otsuchi, Iwate prefecture. They don't have water here and are forced to wash their dishes and clothes in the nearby river, in water that is still frigidly cold from the long winter months.

Boredom is setting in; there's not much to do here. In this particular evacuation centre, there are only two children. One young boy spends his time blowing up a plastic bag and making an impromptu balloon. We take turns kicking it to each other. And now they have to move. From the relatively heated comfort of the large facility they are in, to smaller huts; huts that will be plunged into darkness when night falls. There is as yet no electricity.

I chat with Kimito Iwama, a man who spends his day clearing the roads. He lost his home, and his parents and brother are still missing. At the end of every day, he goes looking for them before heading to an evacuation centre where he helps manage the needs of 140 of his neighbours.

"I am afraid we will lose the attention of the media," he says; when the media move on, the world often forgets. "Please don't forget about us."

Day Seven

"The earthquake saved my life."

It's a strange thing to hear, coming from the chief nurse in the maternity ward at the Red Cross hospital in Ishinomaki. Yukie Masaka (39) was at her seaside home when the 9.0 magnitude quake shook it to its core.

As a nurse for many years, and having experienced several earthquakes, Yukie realized that this one was serious. She knew there would be a lot of people hurt.

Nurses are juggling routine work with helping the thousands of quake victims

Her nursing instinct and desire to help others kicked in immediately. Yukie hopped into her car and sped to the hospital. "If I had left five minutes later, I would be dead," she tells me.

When Yukie had the chance to return to her home, she found it in ruins; everything was gone. She now lives with friends.

Yukie does not focus on what she has lost. Instead, she directs her energy to helping the thousands of extra patients who now cross the threshold of the hospital in which she works.

At the end of her 22-hour shift, despite her weariness, she agrees to take a few minutes to talk with me.

She tells me that time flies very quickly; there is so much to do. Not only does she oversee patient care in the maternity ward, she is also in charge of all the administrative duties.

They have enough medication to assist new mothers, what they need is more staff. "Our staff are so exhausted," she says quietly.

And yet, amid the exhaustion, death and destruction, there is new life, and Yukie and her staff are witness to it.

There have been 60 babies born at this hospital since the earthquake and tsunami, many to mothers who lost loved ones on 11 March. It is the strength of these mothers that gets Yukie through her 22 hour shifts.

"I am amazed by the mothers' almost primal need to protect their child," says Yukie. "Their will to protect their unborn child is so strong. That gives me a lot of strength."

Day Six

I walk into the evacuation centre in Yamada in north-east Japan. The first thing I notice is the hundreds of makeshift sleeping quarters mapped out on the gymnasium floor. The second thing I notice is a big smile on the face of one man.

It strikes me as odd. How can he smile, I wonder, given that he is now homeless and has just lived through the unimaginable. I want to know more about this man. I ask my translator and he is introduced to me as Ken Minato, a 67-year-old fisherman.

Ken Minato (L) is encouraging other tsunami survivors with his infectious smile

Ken is warm and welcoming, his handshake strong and firm. He starts to share his story. He was at work when the tsunami struck, at a fishing office with an ocean view that would be the envy of almost anyone.

The water poured in and his colleague went to check on the boats. It was the last time he would see his friend.

Ken ran up into the hills. He watched as the water rushed through the walls of his office. He talks about people running to a place that had been considered a safe evacuation centre. The tsunami struck there too. What the tsunami didn't strike, fire later destroyed.

My curiosity gets the better of me and I ask Ken about his ability to still smile.

"I have to live on," he says, "so I have to smile. I have no reason to stay in grief."

His smile is helping others who now call this gymnasium home. "We are all encouraging each other," he says. "I don't know how long we will be here. But I don't want to leave, unless we can all leave together."

It is a comment that couldn't help but make me smile.

Day Five

Amid all the destruction, it is a safe haven. As everything around it was engulfed by the raging waters of the tsunami and the subsequent fires triggered by ignited fuel, the Shinto shrine in Otsuchi stood tall and strong.

The Matsuhashi family, whose home burned after the tsunami, now live with 18 others in a shrine

It is now home to 22 people of all ages who managed to make it through that awful day. I spend a few hours visiting here, getting to know a family of four, the Matsuhashi family.

Tomoyuki, 41, is the keeper of the shrine and he was working there when the ground shook like never before.

He tells me how he ran to the room where his invalid father lay, to stop furniture from falling on him. He heard firefighters issuing warnings to evacuate because of the approaching tsunami. Soon after he saw the massive cloud of dust created when the giant wave crushed every house that stood in its way.

His father told him to go, to leave him and save himself. Tomoyuki refused, forcefully carrying his father up into the safety of the hills. Other elderly people could be seen climbing out of windows and scrambling to safety.

They watched as the water crept closer to the 360-year-old shrine. But it stopped at the first step. They saw flames from a forest fire creep closer from the other side. But they too stopped within a few feet of the shrine.

Tomoyuki believes that God protected the shrine that day. One has to wonder, when this one building remains intact while everything around it lies in ruins.

Day Four

It is freezing here in northern Japan. Every day we are driving through heavy snow. At night, the mercury dips below zero. I shudder as I climb into my sleeping bag, beneath the blankets of the hotel bed, not even bothering to change out of my clothes. Fuel is still being rationed, so there is no heat here.

Fuel shortages mean that many are experiencing severe cold in evacuation centres

And as I drift off, I think about how cold the people in the evacuation centres must be. I visited one in Yamada, a youth centre that is now housing approximately 40 handicapped elderly tsunami survivors. They can't feed themselves. They can't take care of themselves. They can't move.

During the day, these frail, crumpled people sit bundled up in blankets around the space heater that is inadequate to warm the large common room. At night, they are moved to individual sleeping quarters, where there are no heaters. I wonder - will they have survived the devastating events of 11 March only to succumb to the cold?

Japanese Red Cross doctors tell me they are now treating more patients for influenza and hypothermia. Body temperatures are plummeting in the cold weather. People, particularly the vulnerable elderly population, are shivering and confused. It is a challenge to meet their needs.

Red Cross teams have searched but cannot find adequate shelter for them. Even if they did find better accommodation, there isn't the fuel to transport people and most don't want to leave. They want to stay in surroundings they are familiar with, even if those surroundings are full of broken buildings, twisted metal, and overturned cars.

Day Three

On a normal day, the gym at this youth centre in Yamada, Iwate prefecture, would be filled with kids, shooting hoops, or playing volleyball or badminton. But these are not normal days. This gym is now doubling as an evacuation centre; it is home to almost 300 earthquake and tsunami survivors.

Katsuko (R) and her husband Kisaburo

They huddle together on blankets on the floor, their meagre belongings crammed tightly into plastic bags form a mini-fortress around their allotted space.

An elderly couple invite me to sit. Katsuko does all the talking. Her husband, Kisaburo, is now 80 years old, and his hearing is failing him. She tells me their house is on top of a hill and survived the disaster, but they don't have water or electricity so they now live in the evacuation centre.

She talks about losing her brother, nieces and nephews when the giant waves swept through their town. She says many more are still missing, but she doesn't cry. She says she can't show tears. She is not the only one who is suffering.

Katsuko says she is grateful for the three meals she and her husband are receiving at the centre, for the heat that is provided. She has managed to have two showers since the tsunami, humbly visiting a relative's house to do so.

Katsuko says she needs nothing, explaining that she can at least return to her house to retrieve clothing. She wants us to focus on her neighbours, who lost absolutely everything.

These are long days in the evacuation centres. There is not much to do, but Katsuko doesn't complain. She passes the time sleeping, chatting with other ladies, and walking around the centre to keep in shape.

She and Kisaburo have experienced a lot during their 50 years of marriage. When I ask for their wedding date, she laughs, saying she can't remember. It is then her husband speaks for the first time. "January 16th," he says with a smile. "You shouldn't forget that!" A small moment of levity at a time when laughter is hard to come by.

Day Two

Today we visited Iwate prefecture, one of the areas hardest hit by the earthquake and tsunami. Sitting north of the epicentre, more than 70km of its coastline was obliterated by the 10m-high wave.

Snow flurries and cold temperatures are hampering relief efforts in north-eastern Japan

Electricity, for the most part, is still out. The main water supply has been severed and more than 45,000 survivors are now housed in 370 evacuation centres. Their immediate needs are a regular supply of food, water, warm clothing, heat, medicines and bedding.

A Japanese Red Cross logistician tells me that people are happy to see him and his team. But he admits they can't adequately meet people's needs, largely because there isn't enough fuel to get supplies or aid workers where they need to go.

On the way to Yamada town, where he is working, we passed many petrol stations that were closed; others had queues of cars stretching for kilometres.

Even though some were making emergency vehicles - like those of the Red Cross - a priority, we were still allowed to get only 10 litres at a time.

The lack of fuel is one of several obstacles in the struggle to help the people of Japan get back on their feet.

But things are expected to improve in the near future. One of the country's largest oil refineries is back on-line, and that should help ease the shortage.

Until that happens, I'm afraid recovery is going take longer than anticipated.

Day One

It is my first full day in Japan after arriving from Pakistan, where I was working on flood relief operations for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

Kathy Mueller: "Aftershocks is one of the main topics of conversation among colleagues"

Aftershocks is one of the main topics of conversations among my colleagues at the Japanese Red Cross headquarters here in Tokyo. The building is a hub of activity as local staff, dressed in their grey and red emergency gear, co-ordinate everything from the logistics of engaging in such a large-scale relief operation, to determining where to next deploy their medical teams.

The fear of radiation contamination from the Fukushima nuclear plant is also much discussed. Today I head into the field; towards Fukushima to meet with one of the Red Cross disaster management teams working in the area. My supervisor reminds me that if I am at all concerned, I don't have to go.