Myanmar profile - Overview

- Published

Myanmar, also known as Burma, was long considered a pariah state, isolated from the rest of the world with an appalling human rights record.

From 1962 to 2011, the country was ruled by a military junta that suppressed almost all dissent and wielded absolute power in the face of international condemnation and sanctions.

The generals who ran the country stood accused of gross human rights abuses, including the forcible relocation of civilians and the widespread use of forced labour, including children.

The first general election in 20 years was held in 2010. This was hailed by the junta as an important step in the transition from military rule to a civilian democracy, though opposition groups alleged widespread fraud and condemned the election as a sham.

It was boycotted by the main opposition group, Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) - which had won a landslide victory in the previous multi-party election in 1990 but was not allowed to govern.

A nominally civilian government led by President Thein Sein - who served as a general and then prime minister under the junta - was installed in March 2011.

However, a new constitution brought in by the junta in 2008 entrenched the primacy of the military. A quarter of seats in both parliamentary chambers are reserved for the military, and three key ministerial posts - interior, defence and border affairs - must be held by serving generals.

Despite this inauspicious start to Myanmar's new post-junta phase, a series of reforms in the months since the new government took up office has led to hopes that decades of international isolation could be coming to an end.

This was confirmed when US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton made a landmark visit in December 2011 - the first by a senior US official in 50 years - during which she met both President Thein Sein and Aung San Suu Kyi.

The newly re-elected President Obama followed suit in November 2012, and hosted President Thein Sein in Washington in May 2013, signalling the country's return to the world stage.

The EU followed the US lead, lifting all non-military sanctions in April 2012 and offering Myanmar more than $100m in development aid later that year.

Ethnic tensions

The largest ethnic group is the Burman or Bamar people, distantly related to the Tibetans and Chinese. Burman dominance over Karen, Shan, Rakhine, Mon, Rohingya, Chin, Kachin and other minorities has been the source of considerable ethnic tension and has fuelled intermittent protests and separatist rebellions.

Military offensives against insurgents have uprooted many thousands of civilians. Ceasefire deals signed in late 2011 and early 2012 with rebels of the Karen and Shan ethnic groups suggested a new determination to end the long-running conflicts, as did a draft ceasefire agreement signed between the government and all 16 rebel groups in March 2015.

Simmering violence between Buddhists and the Muslim Rohingya erupted in 2013, the official response to which raised questions at home and abroad about the political establishment's commitment to equality before the law.

A largely rural, densely-forested country, Myanmar is the world's largest exporter of teak and a principal source of jade, pearls, rubies and sapphires. It has highly fertile soil and important offshore oil and gas deposits. Little of this wealth reaches the mass of the population.

The economy is one of the least developed in the world, and is suffering the effects of decades of stagnation, mismanagement, and isolation. Key industries have long been controlled by the military, and corruption is rife. The military has also been accused of large-scale trafficking in heroin, of which Myanmar is a major exporter.

The EU, United States and Canada imposed economic sanctions on Myanmar for some time, and among major economies only China, India and South Korea have invested in the country.

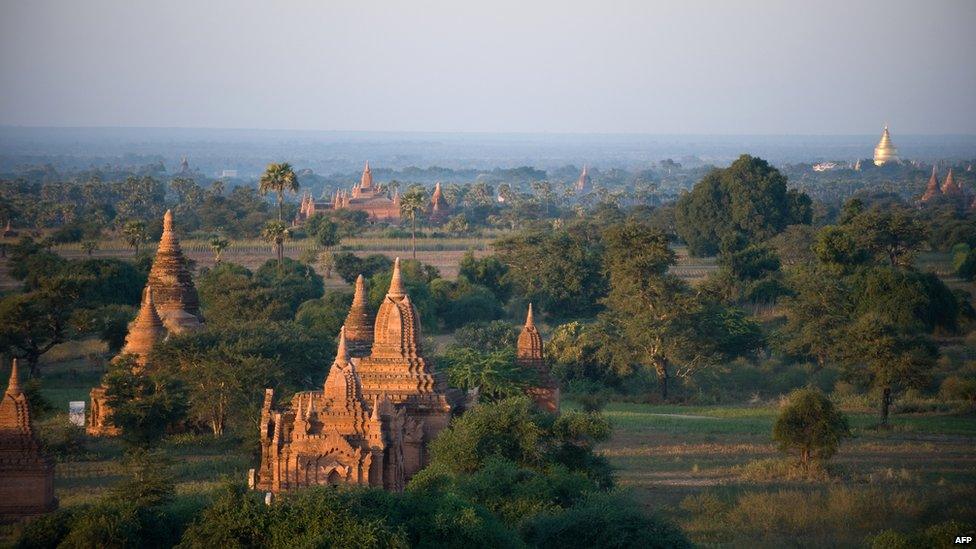

Myanmar's wealth of Buddhist temples has boosted the increasingly important tourism industry, which is the most obvious area for any future foreign investment.

The ruined city of Pagan, capital of the Kingdom of Pagan, which first united what is now Burma in the 11th century