The dark side of South Korean pop music

- Published

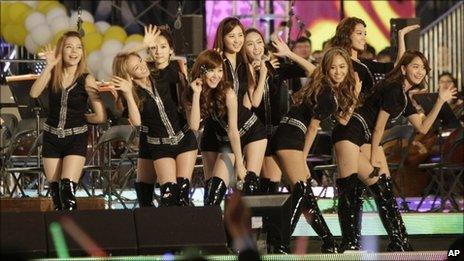

K-Pop sensations Girls' Generation on stage in Seoul

South Korea's pop industry is big business in Asia. As K-Pop sets its sights on Europe and the US, will this force a change in the way it treats its artists?

Selling singles is no way for a pop star to make money these days. Most artists find that touring and merchandise sales are more lucrative. So when it comes to concerts, size matters.

This is why the biggest date in the Korean pop calendar - the Dream Concert, at which up to 20 bands perform - is held in Seoul's 66,800-seat World Cup Stadium.

Teenage crushes come here for a once-a-year date in a national love story, where commitment is measured in coloured balloons, and devotion is knowing all the words.

Most of the bands, like Super Junior, external and Wonder Girls, external, are household names; highly produced, sugary boy- and girl-bands with slick dance routines and catchy tunes.

But the industry also has a less glamorous side: a history of controversy and legal disputes over the way it treats its young artists, which it is still struggling to shake.

Fans of K-Pop star Rain helped him nab top spot in Time's list of influential people

K-Pop is a massive industry: global sales were worth over $30m (£18m) in 2009, and that figure is likely to have doubled last year, according to a government website.

Industry leaders are also ambitious - Korean stars are beating a path to Japan, America and Europe. This month, South Korea's biggest production company, SM Entertainment, held its first European concert in Paris, part of a year-long world tour.

In April, Korea's king of pop, Rain, external, was voted the most influential person of the year, external by readers of Time magazine. And earlier this year, boy band Big Bang, external reached the top 10 album chart on US iTunes.

Follow the money

Korea is excited by what this new musical export could do for its image - and its economy.

But some of K-Pop's biggest success stories were built on the back of so-called slave contracts, which tied its trainee-stars into long exclusive deals, with little control or financial reward.

Dong Bang Shin Ki took their contract fight to court

Two years ago, one of its most successful groups, Dong Bang Shin Ki, external, took its management company to court, on the grounds that their 13-year-contract was too long, too restrictive, and gave them almost none of the profits from their success.

The court came down on their side, and the ruling prompted the Fair Trade Commission to issue a "model contract" to try to improve the deal artists got from their management companies.

Industry insiders say the rising success of K-Pop abroad, and experience with foreign music companies, has also helped push for change.

"Until now, there hasn't been much of a culture of hard negotiation in Asia, especially if you're new to the industry," says Sang-hyuk Im, an entertainment lawyer who represents both music companies and artists.

Attitudes are changing, he says, but there are some things that even new contracts and new attitudes cannot fix.

Rainbow's singers put in the hours

Rainbow, external is a seven-member girl-band, each singer named after a different colour. If any group could lead to a pot of gold, you would think they would.

But Rainbow - currently in a seven-year contract with their management company, DSP - say that, despite working long hours for almost two years, their parents were "heartbroken" at how little they were getting paid.

A director for DSP says they do share profits with the group, but admits that after the company recoups its costs, there is sometimes little left for the performers.

K-Pop is expensive to produce. The groups are highly manufactured, and can require a team of managers, choreographers and wardrobe assistants, as well as years of singing lessons, dance training, accommodation and living expenses.

The bill can add up to several hundred thousand dollars. Depending on the group, some estimates say it is more like a million.

Musical exports

But music sales in South Korea alone do not recoup that investment. For all their passion, home-grown fans are not paying enough for K-Pop.

The CD industry is stagnant, and digital music sites are seen as vastly underpriced, with some charging just a few cents a song.

Girl band 4minute on tour in the Philippines

Bernie Cho, head of music distribution label DFSB Kollective, says online music sellers have dropped their prices too low in a bid to compete with pirated music sites.

"But how do you slice a fraction of a penny, and give that to the artist? You can't do it," he says.

With downward pressure on music prices at home, "many top artists make more money from one week in Japan than they do in one year in Korea", Mr Cho says.

Company representatives say concerts and advertising bring in far more than music sales. "Overseas markets have been good to us," says one spokesman. South Korean musicians need to perform on home turf, but "Japan is where all the money is".

As acts start to make money overseas, he says this "broken business model" - underpricing - is creeping into their activities abroad.

A former policy director at South Korea's main artists' union, Moon Jae-gap, believes the industry will go through a major upheaval. "Because at the moment, it's not sustainable," he says.

Until that happens, he says, artists will continue to have difficulty making a living.

South Korea's government is keen to promote its new international identity, one many hope could rival Japan's cool cultural image.

The only question is whether the industry ends up more famous for its music, or for its problems.