US firm Freeport struggles to escape its past in Papua

- Published

The Papua mine reputedly holds the biggest reserves of copper and gold of any mine in the world

The US mining firm Freeport McMoRan has been accused of everything from polluting the environment to funding repression in its four decades working in the Indonesian province of Papua. A recent spate of strikes by workers has brought all those uncomfortable allegations back to the surface.

"Ask any Papuan on the street what they think of Freeport, and they will tell you that the firm is a thief," said Neles Tebay, a Papuan pastor and co-ordinator of the Papua Peace Network which campaigns for more rights for local people.

"It is in the interests of the Indonesian government that Freeport stays in Papua because it pays so much money to the state."

For decades, a small number of Papuans have fought an armed struggle for independence from Indonesia.

But Neles Tebay believes the US mining firm plays a crucial role in that struggle: "Papua will never become independent as long as Freeport is in Papua."

Yet Freeport says it provides vital jobs and wealth to the people of Papua. It is a decades-old row.

Massive profits

In the mid-1960s, Indonesia was undergoing a political transformation - and facing potential economic collapse. The government led by General Suharto was desperate to gain legitimacy with the international investment community - a hard task when Indonesia was seen as a risky market.

Suharto got the legitimacy he was looking for in 1967 - when Freeport became the first foreign company to sign a contract with the new government. In exchange, Freeport got access to exploration and mining rights for one of the most resource rich areas in the world.

In 1988, Freeport literally struck gold, finding one of the largest known deposits of gold and copper in the world at Grasberg in Papua.

Today, Freeport is one of Indonesia's biggest tax-payers. In the last five years the firm says it has paid about $8bn (£5bn) in taxes, dividends and royalties to the Indonesian government. In the second quarter of this year alone, the company saw its profits double to $1.4bn.

But all of that money has yet to buy Freeport the reputation it needs in Papua. Thousands of Papuan workers walked out last month complaining about their wages, which they say are a fraction of what their international counterparts get.

Most Papuans believe that a contract Freeport signed with the Indonesian government in 1967 is invalid, because it was signed two years before Papua was officially incorporated into Indonesia by a controversial referendum.

The company says it signed a new 30-year contract with the Indonesian government in 1991, with provisions for two 10-year extensions.

But Papuans dispute the length of the deal, and the number of extensions Freeport has been able to get from the Indonesian government. Critics say Suharto wrote a blank cheque for Freeport, allowing the company to operate in any way it chose with little regard for consequences.

"The initial contract started in 1967, and was meant to end in 1997," said Singgih Wigado, director of the Indonesian Coal Society.

"But in 1991, Suharto's government renewed it - and then extended it for another 30 years, so now it ends in 2021. But Freeport is also entitled to two extensions during this period - of 10 years each. So Freeport's contract really only ends in 2041."

'Law unto themselves'

By then, environmentalists allege that Freeport will have not only ripped all of the mineral wealth from Papua's soil but it will also have destroyed the local waterways and killed off the marine life in the rivers nearest to the mine.

The lobby group Indonesian Forum for the Environment accuses Freeport of dumping hazardous waste into rivers.

"We've seen no improvements in their operations. The local communities are suffering because of Freeport's presence in Papua," said the group's Pius Ginting.

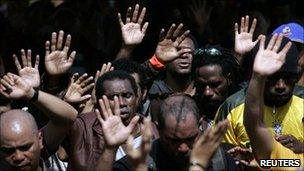

Thousands of workers walked out in protest at their pay

But Freeport disputes the claims, saying that it uses a river near the mine to transport waste and natural sediments to a large deposition area. This method, the company says, was chosen because studies showed it was the most feasible way of disposing of the waste, and the environmental impact caused by its waste material is reversible.

In a statement, the company argued that the current arrangement with the government was fair, and has resulted in significant benefits.

Some of those significant benefits include providing employment to scores of Indonesian police who are mandated by Indonesian law to protect the Grasberg mine. This used to be the job of the Indonesian military, who are still sometimes asked to provide extra support for the mine by the police.

Freeport estimates that it spent $14m on security-related expenses in 2010.

But human rights groups say Freeport is effectively financing the Indonesian military in Papua, and is turning a blind eye to the soldiers' alleged human rights abuses in the province.

Andreas Harsono of Human Rights Watch says there are about 3,000 troops in the area, some of whom "tend to act as a law unto themselves".

"They sometimes go beyond their duties of providing security to Freeport - and are also believed to be involved in illegal alcohol sales and prostitution," he says.

The Indonesian military has consistently denied any wrongdoing in Papua.

Freeport defends its use of police and soldiers to guard the Grasberg mine, saying it is mandated under Indonesian law. Freeport has never been implicated in any human rights abuses allegedly committed by the Indonesian military in Papua.

Nevertheless, the company remains hugely controversial in the restive province.

"Freeport is a symbol of everything that is wrong with Papua," said pastor Neles Tebay.

"Indigenous Papuans want to feel like they have control over their own future - and that means a right to safeguard their natural wealth."

The BBC has requested to travel to Papua and visit the Grasberg mine, but access has so far been denied by Freeport.

- Published13 July 2011