South Korea military faces 'barracks culture'

- Published

Calls for reform within South Korea's military are growing

Becoming a man means becoming a soldier - at least that is what the army in South Korea says. But a spate of deaths is leading some to call for wholesale change in the way the military operates.

Military service is a rite of passage here, and most new army conscripts begin their service at the army's main training base in Nonsan, playing ear-splitting war-games under the watchful eye of Colonel Kim Hyung-gyul.

Military training has been tightened in South Korea this year. An attack by North Korea last November refocused attention on the country's armed forces - largely composed of conscripts - and led to calls for a tougher response.

Col Kim said there were already concerns within the military that the new recruits were softer than in the past and less adaptable to military life.

The training, he said, has been intensified and focused into specific areas, to make the soldiers battle-ready.

"Each recruit is individually checked as an incentive to train harder," he said.

All this training is to prepare the new recruits for external enemies, but the military is also facing a threat from within; a barracks culture that some say is helping to kill its soldiers before a real shot has been fired.

Last month, a marine corporal shot and killed four of his comrades. He said he was being bullied.

Several other soldiers killed themselves in the weeks that followed. Since then, South Korea's defence ministry has brought out new orders banning beating, cruelty, humiliation and bullying within the armed forces, to tackle what it calls a "distorted military culture".

Calls to military helplines have shot up since the recent spate of deaths. But the issue of soldiers dying in their barracks has overshadowed the military here for decades. And the deaths have often been left unexplained.

Basic rights

Chai Yeil-pyung and Park Eun-eui lost their youngest son 10 years ago, while he was on military service. Despite several investigations, they still do not know how he died.

"If the nation calls upon our sons, it has a duty to return them safe and sound," said Mr Chai.

"But for us to be left like this, not knowing even the cause of my son's death, I think that's a great betrayal of a citizen and a parent."

Five years ago, a presidential commission was set up to investigate suspicious deaths in the military.

Kim Ho-chul was one of the investigators. In the past, he says, it was clear the army had "an instinct of self-preservation".

There are concerns new recruits are softer than in the past, and less adaptable to military life

Investigations, he said, were often "very insufficient" and there was "a lack of will to seek the truth, and a lack of explanations for the family".

In the past 30 years, he said, the number of non-combat deaths has fallen dramatically - from 800 a year, to around 100. But while military investigations into these deaths have improved, he said attitudes on the ground still need to change.

"There needs to be a major change in thinking towards soldiers in the first place," he said. "They are citizens in uniform, and I think there needs to be a better awareness of their basic rights."

Back at the training camp, Col Kim said the culture within the military is changing - slowly.

"This barracks culture isn't something that can change overnight, just for the show of it," he said. "It needs to change slowly. I think we need to continue the work we've been doing."

And, he added, the conscripts themselves were different now.

"Twenty years ago, the conscripts that came to this place were a lot more country-oriented, their mindset was to serve their country," he said. "Now they're more individualistic.

"But rather than just rejecting this new style of conscript, I think we need to adapt to them and change our training to fit these new types of soldiers."

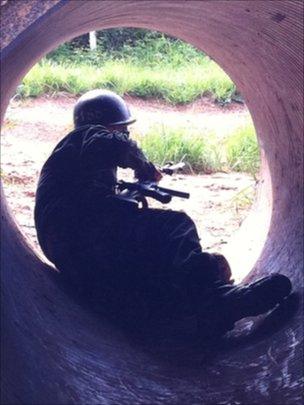

On the edge of the pretend battle-field, lines of recruits carry out weapons drills, their faces smeared with camouflage paint, their boots immaculate.

In June, many of them were still university students. For the next two years, they will be soldiers. And while life in South Korea may have changed immeasurably since their fathers' time, the threat of war on the Korean Peninsula has not.

- Published29 June 2011

- Published18 June 2011