North Korea's resort seizure ends project of hope

- Published

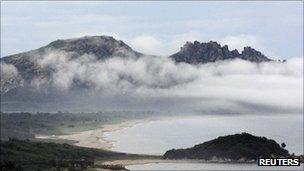

Thousands of South Korean tourists used to travel each year to Mt Kumgang

The opening of North Korea's Mount Kumgang to South Korean tourists led to hope, bordering on euphoria, of reconciliation between the two hostile states.

The North's decision to seize South Korean assets at the tourist resort site and expel the remaining Southern officials looks like a dismal end for the project.

A North Korean spokesman accused the South of breaking its agreements over the resort.

"There will be neither magnanimity nor generosity for such hooligans ...the puppet group has no intention to resume the tour of Mt Kumgang and is using noble tourism for the purpose of confrontation," the spokesman said.

The resort opened in 1998. Then, for the first time in almost half a century, South Koreans were allowed to enter the once hermetically-sealed North of the peninsula.

First they came by boat, but within a few years, thousands of visitors were crossing by land through the front lines of the world's most heavily-fortified border.

There are still no telephone or postal links between the two states and unauthorised contacts between individuals are strictly forbidden.

The route to the resort was tightly controlled to restrict interaction between tourists and locals

But each day, convoys of tourist buses would snake through the demilitarised zone - a once unimaginable journey through a no-man's land of tank traps and minefields, flanked by two of the world's largest armies.

The apparent success of the Mt Kumgang resort was the high-water mark of South Koreas "sunshine policy" - an attempt to prise the North out of its isolation by encouraging economic co-operation and personal contacts.

But the reality was never as encouraging as the rhetoric. South Koreans were only allowed onto clearly marked trails in an isolated mountain wilderness just north of the DMZ. Contact with the population was out of the question.

Bewildering experience

Before leaving the South, the visitors were ordered to hand over their mobile phones, computers and newspapers to their guides.

They were warned not to take photographs on the journey and to avoid any sensitive topics during encounters with the small number of North Korean "guides" they would encounter on the trails.

It was a bewildering and disheartening experience for many of the South Korean tourists - up to 300,000 a year - who had dreamed of national reunification or finding long-lost relatives.

They found everything was immediately and depressingly different on the other side, even inside the demilitarised zone itself. The Northern half is barren and eroded, cleared of the lush foliage to open up fields of fire for the army.

The road - built exclusively for the tourists - was sealed off from the North Korean countryside by a high wire fence. The designated tourist zone at the foot of Mt Kumgang's trails was also fenced off.

Armed North Korean soldiers with red flags stood at the entrance of neighbouring North Korean villages.

Get too close and a guard would angrily wave his flag and slap the gun at his side.

Shot dead

It became clear that the North Koreans wanted money from the South Koreans - a fixed sum for each visitor - but would do everything possible to prevent meaningful contact between people.

The Mt Kumgang project was a key symbol of inter-Korean rapprochement

In 2008, tragedy occurred. A 53-year-old South Korean woman was shot dead by one of the guards and the South Koreans suspended the tours.

Hopes for reconciliation were already on the slide. The conservative government of President Lee Myung-bak in South Korea had reversed the "sunshine policy" of his liberal predecessors.

He cut the big annual shipments of free rice to the North. Such largesse would now be conditional on the North Koreans shutting down their nuclear weapons programmes.

North Korea's decision to seize the tourist complex at Mount Kumgang underlines the return to confrontation. It follows North Korea's artillery attack on a South Korean island last year and allegations that it sunk a South Korean warship.

But optimists in the South say that all is not lost.

Both sides still appear committed to the other big joint project - at the opposite, western, end of the DMZ.

There 120 South Korean firms continue to produce light industrial products at the Kaesong industrial park.

Some 46,000 North Koreans are employed at the factories earning just over $60 a month. There have been disputes and the North Koreans have, on occasion, blocked access across the DMZ.

But Kaesong is a source of badly-needed hard currency for the North, and the South Koreans have plans to keep their industry competitive by exploiting vastly cheaper Northern labour.

The two sides are still reluctant to sacrifice those benefits on the altar of tit-for-tat diplomacy.

But the North Koreans do appear to have given up hope of extracting further financial gains from the South, at least while President Lee remains in power.

The state media has reverted to old insults in its references to the South - denouncing the government as puppets, thieves and hooligans.

Looking elsewhere

North Korea is now looking to its closest ally, China, to revive the tourism project - although without the emotional draw of national brotherhood and reunification, it is doubtful the area will have much appeal to Chinese tourists.

Kim Jong-il has gone to Russia to seek aid and economic co-operation with Moscow and the North Korean leadership is also sending possible signals to the United States.

North Korea is well practiced at playing off its neighbours against each other and exploiting regional rivalries.

The concern is that some in the leadership will want to go further and punish the South Koreans for their defiance.

In recent years, when tensions have been high across the DMZ, it has felt the need to test ballistic missiles and nuclear devices to show off its destructive power.