China answers Zambian critics

- Published

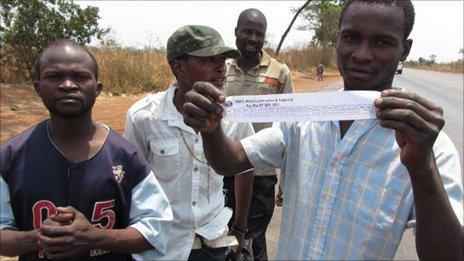

Zambian workers complain about low wages

The behaviour of Chinese companies in Zambia, and how they treat their African workers, was an underlying issue in the recent elections. Some Chinese companies say they are taking steps to deal with the problem.

A year ago this month, coal miner Taska Chinko was in a crowd of Zambian workers gathered outside their Chinese managers' living quarters at Collum coal mine in Zambia.

Chinko says that instead of trying to talk with the workers, who were demanding more pay, the Chinese managers went to get their air guns.

One of many Chinese construction sites in Lusaka

Chinko still can't believe what happened next.

"When you saw the management coming out with guns, we felt so bad - because we are not like animals, where they have to use guns to keep us away."

Shots were fired and 12 miners were wounded, two of them critically.

The miners responded by running amok and looting a Chinese compound - exactly what the Chinese managers said they'd been trying to prevent.

Eventually, things calmed down. The injured were compensated. The Chinese managers were arrested - though a few months later the case was dropped and the managers went back to China.

Zambians acknowledge the Chinese have brought the country much-needed money and jobs as they continue to invest in a region rich in natural resources.

But the Collum mine incident has not been forgotten by Zambians who feel their government has had too cosy a relationship with Chinese investors.

Last month, they elected a new president, Michael Sata. He'd spoken out for years about the need to get a fairer deal for Zambian workers, and Zambia itself, from the Chinese.

Although it's a natural fit for Zambia, the world's largest producer of copper, and China, the world's largest consumer of copper to do business, many Zambians believe their country could and should do better out of the deal.

Man management

In the past year, the four Chinese brothers who own Collum coal mine have made some changes.

They've doubled salaries for coal miners, though workers say they still earn barely enough to live on, and don't get paid at all when the mine does not need them.

The brothers have also hired a Zambian human resources officer, Corry Moono.

"Basically, my role is to make sure the labour laws of this country are adhered to, to protect the interests of this company, and the interests of the workers."

But he says, that's not quite how the company, or the workers, see him.

"The workers, they don't understand. They say, 'You are siding with the Chinese.' And the Chinese say, 'You are siding with the black guys.'''

Though his bosses may not fully appreciate his efforts, Moono says since he arrived at the mine nine months ago, the fact that he was there to communicate with the workers in their language, and treat them with a little respect, helped to avert three near-riots.

"I've said, 'Boys, let's work together,'" Moono says. "'Our investors are here to make money, and you're here to earn a living'. When I talked to them like that, they to some extent understood."

That does not mean they are happy.

Coal miner Taska Chinko says he and fellow miners get no paid days off. The poor ventilation in the mine is affecting his lungs. And he even had to buy his own helmet.

Chinko says if he could, he'd find another job.

Hundreds of miles to the north, in Zambia's copper belt, the coal from the Collum mine helps fuel Chinese copper smelting.

Workers there voice similar gripes. Many make less than $200 a month - and most of that is eaten up in rent.

Chinese companies say they are paying at least the minimum wage, so are not breaking the law.

But Goodwell Kaluba, General-Secretary of Zambia's National Union of Mine and Allied Workers, says the minimum wage is meant for safe, sedentary jobs like sales clerks - not miners.

Nevertheless, he accepts some Chinese companies are making a big effort to improve relations.

One of them is the Shanghai Construction Group, a listed, majority state-owned Chinese company.

"We are trying to use more local people," says Wu Jiang Rong, a project manager. "We try to train local labourers to improve their skills. A lot of them, when they come, are general labourers. After a few months, they are painters, carpenters, bricklayers."

A brighter future?

Just days after Michael Sata was elected president last month, he met Chinese Ambassador Zhou Yuxiao. Zhou wanted to convey the congratulations of Chinese President Hu Jintao - though the Chinese Communist Party had openly backed the incumbent.

President Sata listened politely as the ambassador read out Hu's letter, then was pointed in his own comments.

"We welcome your investment, but your investment should benefit the Zambians," he said. "Both of us must benefit. It must be two-way traffic."

He added that Chinese companies must abide by local laws, and observe limits on how many foreign workers they bring in to the country - a popular complaint in Zambia, as many Chinese companies use workers from China to do jobs Zambians could do.

Ambassador Zhou told President Sata that Chinese companies should always follow the law of the land, and should be held accountable if they do not.

Later, he told me he thinks Chinese companies get unfairly singled out for criticism in Zambia.

"The Chinese companies here in Zambia are as good as the Chinese companies working in other countries. I've been working in many African countries," he said. "But the companies [in Zambia] are portrayed in a much worse way - maybe not so much because of the performance of the Chinese company, but mainly because of the political setting here."

But Zhou acknowledges there's still room for improvement in how Chinese companies do business in Zambia. And many Zambians would agree.

Mary Kay Magistad is China correspondent for PRI's The World, a co-production of the BBC World Service, Public Radio International, and WGBH in Boston. Read more of her reporting from Zambia at PRI's The World, external.