Can China control social media revolution?

- Published

Microblogs give people the opportunity to share information and speak out like never before

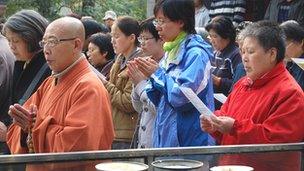

At first sight, Longquan Temple, which sits at the foot of a mountain just outside Beijing, seems like an odd place to look for the modern world.

Buddhist monks have been performing complicated rituals in its incense-filled halls and courtyards for more than 1,000 years.

But the temple is going through a revival that is being driven by a very high-tech tool - the internet. The abbot even has his own microblog.

Master Xue Cheng is just one of 200 million people who have their own site on China's most popular microblogging portal, Weibo, a service run by internet company Sina.

It has led to a fundamental change in the way people communicate with each other, giving them the chance to share information and speak out.

Microblogging even has the potential to transform China - and its leaders know it. That is why they are now debating how to control this social revolution.

'Embrace new things'

Microblog use has exploded in China over the last couple of years. Twitter is blocked but home-grown alternatives are booming.

Like Twitter, each message is limited to 140 characters, although users can say so much more with that many Chinese symbols than with English letters.

Chinese microblog sites also allow people to attach photographs and documents, increasing the ability to disseminate information.

The range of people who use them is endless: film directors, athletes, television presenters and, of course, ordinary people.

Like elsewhere in the world, they use these sites to talk about anything and everything, much of it trivial, some of it less so.

Master Xue Cheng said his microblog shows that "Buddhists have the ability to embrace new things".

His site is updated regularly with news of events at Longquan and sayings related to his Buddhist beliefs.

"A person is happy not because he possesses a lot, but because he cares for just a few things," was one recent posting from the monk.

The instant messages spread on microblogs have also given Chinese activists a new weapon in their fight against the government.

Information about protests, petitions and government persecution whizz around cyberspace at lightning speed.

The internet is driving a Buddhist revival at Longquan Temple, just outside Beijing

Retired campaigner Wang Lihong realised the value of this new form of communication, using it to gain support for her causes. She helped people with grievances against the government.

The authorities dealt with her, sentencing the 56-year-old to nine months in prison at a court in Beijing in September for "stirring up trouble".

But her message is harder to silence. As she was being led away she told her son, Qi Jianxiang, to remember her on the internet.

Her sentence had been blogged even before she left the courtroom.

Something to ponder?

Chinese people realise their interconnected microblogs have given them a new power to access information and express their opinions.

Activists such as Wang Lihong now have a new weapon in their fight against the government

It is a freedom that they have rarely enjoyed in the 60-odd years since the Chinese Communist Party took power.

I used my own Weibo account to ask people how they thought microblogging was changing China.

The very first response was a simple icon, showing a face with a gag taping the mouth closed. Every now and then, the gag falls away and the mouth opens, as if speaking. The implication seems clear.

Another posting reads: "Microblogs mean people dare speak out - and can speak out. Everything changes when people start to speak the truth."

One man who understands the power of microblogs is Lee Kai-Fu, the former head of Google in China and author of a book on this social phenomenon.

He said microblogging had the potential to change the way China is governed and will, at least, make the country's Communist Party leaders "ponder".

That is something they are certainly doing.

They like to control the flow of information through traditional media outlets to shape what people think - just one of their tools to maintain power.

Microblogging's instant messages undermine that control.

In response, the government started censoring microblogs, as it does other parts of the internet. It has also encouraged officials to set up their own sites, to directly appeal to the public.

It is now threatening to punish those who it claims are abusing the system.

Wang Chen, head of China's State Internet Information Office, said recently that microblogs should "serve society" and not threaten public security.

Zhou Yongkang, a member of the party's all-powerful politburo Standing Committee, hinted at something similar following a major party meeting a week later.

But closing down, or even limiting, a social tool that has so many followers will not be easy, even for an organisation as dedicated to control as the Communist Party.

As the activist Wang Lihong's son said: "Microblogging is like air-conditioning: once you have it, you don't know how you managed to survive without it."

- Published17 February 2011

- Published4 January 2011

- Published2 November 2010