Australia sweats over extreme hot weather

- Published

A sculpture called "We're fryin' out here" at a beach in Sydney

Australia has always suffered from bouts of extreme hot weather but the number and intensity of heatwaves is on the rise, prompting a rethink of how the country lives, works and plays in the sun.

Some like it hot, but the 13-day stretch with temperatures exceeding 40C in Longreach that ended last week was some of the hottest weather in living memory for the Queensland town.

It was also a new heatwave record for the cattle country town, beating the previous record by four days, according to Australia's Bureau of Meteorology (BoM).

Livestock dams began drying up, local companies asked staff to start work early to avoid the worst of the heat and native animals struggled to find water.

It was not an isolated weather pattern. Last year was Australia's hottest since records began in 1910, according to the bureau.

Australia is famous for its beaches, but could soaring temperatures hurt the economy?

Thanks to climate change, much of Australia will be subjected to longer, hotter and more regular spells of extremely hot weather, say climate scientists.

To cope, Australian industry needs to start "heat-proofing" its operations and sporting authorities need to rethink when and for how long competitions are played outside, says Elizabeth Hanna, president of health sector organisation, the Climate and Heath Alliance, and a researcher at the Australian National University.

It also raises questions about the kinds of houses Australians live in, says Ms Hanna, who is in the midst of a four-year project funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council that is measuring how high temperatures can rise before workers and productivity are affected.

Dangers

Much of the research done around the world has looked at how military personnel and elite athletes cope with very high temperatures.

But the average person responds quite differently to very hot weather, she says.

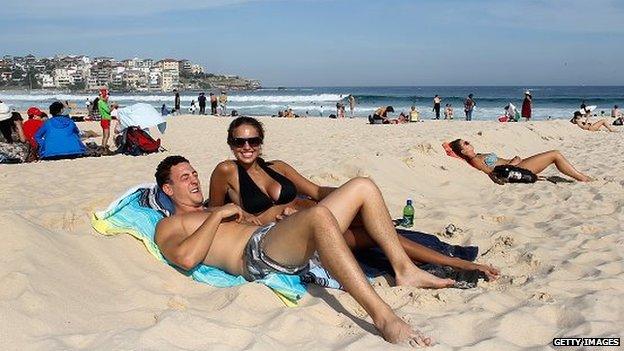

Even in the winter, Australia has been experiencing unusually hot weather

Symptoms of severe heat stress include dizziness, headaches, confusion and fainting. More severe outcomes include dehydration, loss of fluids and electrolytes, and kidney and heart damage.

"I think it will be a big economic impost when people start to opt not to do things because of the heat," says Ms Hanna.

She says sporting authorities needed to rethink holding major events, such as long-distance cycle races and cricket matches, in the peak of summer.

Tennis players at the 2014 Australian Open faced extreme hot weather

Local club sports and recreational participants and organisers must also consider the heat when they plan their games, she says.

"There are some forward-thinking [sporting] people who realise they have to change but it is quite a big deal for all groups to agree on changes," she says.

Tennis Australia is reviewing its hot weather policy after the 2014 Australian Open in Melbourne was disrupted by a week-long heatwave in January.

Organisers of the event - the first of four annual international Grand Slam tennis events - implemented an extreme-heat policy halfway through the tournament when temperatures on the outside courts hit 43C.

For some the heat became overwhelming

The roofs on the central arenas were closed when the mercury hit 43.9C, although play continued.

Football NSW, which represents about 220,000 players, has had a hot-weather policy in place since 2011, says the association's risk manager Michelle Hanley.

"We send a heatwave notice to members alerting them to extreme temperature warnings from the BoM," says Ms Hanley. The association also asks competition managers to consider delaying or cancelling games during heatwaves.

People cope differently with hot weather and different parts of NSW have different conditions "which is why we don't say anyone must cancel a game" she says.

Complacency?

Exercising, working, or even walking at a fast pace becomes difficult at temperatures above 35C, says Ms Hanna, who senses little momentum for change in sport or work places.

"People say 'It's hot and it's always hot in summer,' ... and the message [that the weather is getting dangerously hot] is not coming through in the commercial media," she says.

Experts warn that climate change is making bushfires worse

"About 80% of the energy produced by working muscles is heat, so without heat loss via sweating, we would overheat in about six minutes."

Often, people don't realise the risks of continuing to work outside in such heat, even when they are protected by shade, she says. People can also become lethargic or confused during very hot weather and fail to move out of the heat.

That can be dangerous for anyone caught on public transport without air-conditioning or in cars that break down or are stuck in traffic because of heat-related infrastructure problems.

Heatwaves are occurring more often because of climate change, says climate scientist Sarah Perkins.

The University of New South Wales researcher, who specialises in heatwaves, says Australia is experiencing different types of extreme temperatures, including hotter, longer and more regular periods of heat.

"I am quite concerned that in 2013 we blitzed so many temperature records in Australia," says Ms Perkins.

"For me, it is a screaming climate change signal that we are changing to a new state," she says.

- Published15 January 2014

- Attribution

- Published16 January 2014

- Published16 January 2014