Australia eyes indigenous recognition vote

- Published

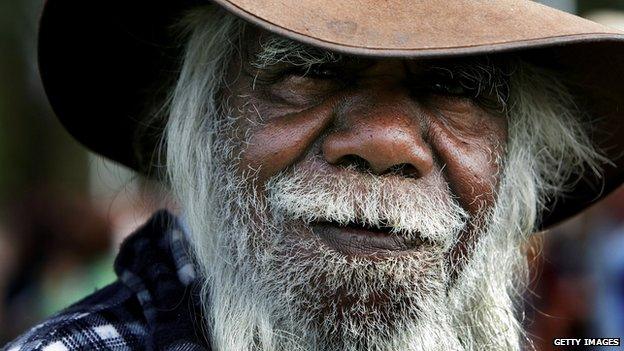

Indigenous Australians represent about 2.5% of Australia's 24 million people

More than a century after its constitution was drafted, Australia is edging closer to formally recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as the nation's first people.

Changing the constitution to recognise the nation's first people is not about politics, says Mike Baird, premier of New South Wales - Australia's most populous state. It's about righting a wrong.

"It is an important part of who we are, it is an important part of our history," he says.

Earlier, this month, Mr Baird became the first state or territory leader to publicly back a federal government campaign - started by the previous Labor government and adopted by coalition Prime Minister Tony Abbott - to reverse the historical exclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people from Australia's constitution.

To do that, the public would have to vote in a referendum.

It was a timely statement. On Thursday, Prime Minister Tony Abbott pledged to hold the referendum in 2017.

One has been promised since 2010 - but getting there could still take years and involve a fraught debate about racial discrimination and whether such recognition really benefits indigenous Australians.

Mr Abbott said he hoped the vote would be held in May 2017 - on the 50th anniversary of the 1967 referendum that approved constitutional amendments relating to the country's indigenous people. But he wanted to be confident the referendum would succeed.

"I do not want it to fail because every Australian would be the loser. It is more important to get this right than to try to rush it through," he told a dinner of supporters on constitutional change in Sydney.

Unlike other settler nations such as Canada and New Zealand, Australia's constitution makes no mention of its indigenous people and still has two so-called "race provisions", including one that allows the states to ban people from voting based on their race.

These, says human rights lawyer George Newhouse, make Australia "now the only English-speaking nation in the world with a constitution that explicitly and intentionally permits its parliament to pass racist laws".

An official Recognise campaign, funded to grow awareness and support for the change, points out that the constitution mentions Queen Victoria, the British parliament, lighthouses, beacons and buoys - but not the first Australians.

The planned constitutional recognition referendum is a "once in a generation opportunity", says indigenous leader Patrick Dodson.

It will, he says, improve Australia's international standing and respect if it gets it right, and attract derision "if we don't".

'Hardness of heart'

There is at least 70% support for constitutional recognition, according to opinion polls.

Tony Abbott: "The worst of all outcomes would be dividing our country in an effort to unite it."

But referendum experts say that support could dissipate if the issue is left to drift for too long, fails to go far enough, or loses bipartisan support.

Mr Abbott said earlier Australia needed to atone for the "hardness of heart of our forebears".

"We have to acknowledge that pre-1788, this land was as Aboriginal then as it is Australian now and, until we have acknowledged that, we will be an incomplete nation and a torn people," he said.

But he has been less enthusiastic about the recommendation from an expert panel of indigenous, business, legal and community leaders that recognition should include strong constitutional protection from racial discrimination.

Critics warn that could expose parliament to excessive court challenges.

"We should be prepared to consider and refine any proposal for some time because it is so much better to get this right than to rush it," Mr Abbott recently said in an oration for Australians for Constitutional Monarchy.

"The worst of all outcomes would be dividing our country in an effort to unite it."

'New nation'

Indigenous Australians represent 2.5% of Australia's 24 million people. Generations of discrimination and disadvantage have left them with poor health and low levels of education and employment.

Indigenous leaders say the constitution has compounded that discrimination and that recognition will help to heal divisions.

Campaigners for indigenous rights staged a protest rally at last month's G20 meeting in Brisbane

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner Mick Gooda says it is the "missing jigsaw piece".

"[A referendum] is not the high court judges or politicians, it's the people saying 'we recognise there were other people here before we arrived', and that could be so powerful it would go to heal a lot of wounds," he says.

"If this gets up, we will wake up the next day to a new nation."

Australian referendum history is not on the side of a "Yes" vote. Changing the constitution requires not only a majority of overall votes, but a majority of votes in a majority of Australia's six states.

Australians have rejected 36 of 44 referendum proposals held since 1900, including one in 1999 that proposed establishing a republic and a preamble recognising indigenous people.

Many high-profile indigenous Australians back recognition - from intellectuals such as Noel Pearson and Marcia Langton to popular footballer and current Australian of the year Adam Goodes, and singer songwriter Archie Roach.

Tens of thousands of non-indigenous Australians and corporate and sporting heavyweights - such as Qantas, Westpac, Cricket Australia and the AFL - have also signed up to support the Recognise campaign.

But others are not convinced. Influential conservative commentator Andrew Bolt says it's a step "on the path to apartheid", while indigenous opponents say it will set back the long-term campaign for a treaty between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians.

Constitutional expert Professor George Williams says the big sticking point is whether the constitution should include a broad prohibition on racial discrimination.

"If it doesn't protect from racial discrimination, I think we will see a very large part of the Aboriginal community losing interest or opposing it," Prof Williams says.

"They, more than any other group in Australia, have been subject to very discriminatory laws that have denied them the vote, the right to marry, to move [from one state to another], to earn a fair wage.

"They want a meaningful response to that. Symbolism just won't cut it."

What's at stake:

The Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples has recommended these changes to the constitution:

Recognising that the continent and its islands now known as Australia were first occupied by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Acknowledging the continuing relationship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with their traditional lands and waters.

Respecting the continuing cultures, languages and heritage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Repealing the two so-called "race provisions":

section 25 that recognises that the states can disqualify people from voting on the basis of their race

section 51(26) that allows laws to be made based upon a person's race.

The committee has suggested three options for replacing section 51(26) to ensure that specific Indigenous laws like native title and heritage protection are preserved and to provide either broad, limited, or no protection on racial discrimination.

- Published2 December 2014

- Published15 September 2014

- Published15 September 2014

- Published13 February 2013