From boom to bust in Australia's mining towns

- Published

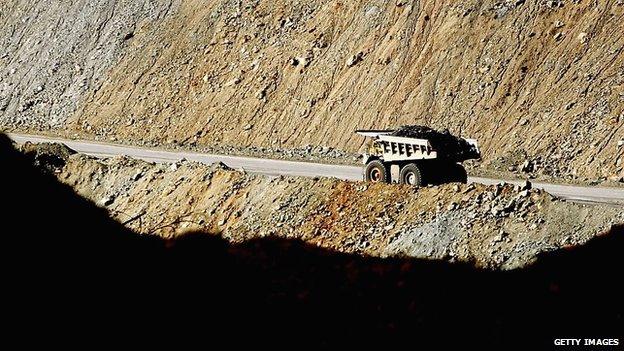

Mining is a mainstay of the economy in small towns like Muswellbrook

After 23 years of growth, including one of the biggest mining booms in the nation's history, tumbling iron ore and coal prices have put a brake on Australia's economy - and mining towns are paying the price.

Peter Windle is a casualty of the mining slowdown. The New South Wales mining employee has lost a well-paid job, a company car and an annual bonus that in some years was as high as A$60,000 ($48,800; £31,300).

A termination package from the mining company he used to work for has helped soften the blow. But Mr Windle still had to sell his investment property to keep his head above water.

Once part of a vast army of workers in what was Australia's booming resources sector, Mr Windle now gets up at 5.30 am five days a week to clean and drive school buses in the small town of Muswellbrook. For decades, the town had ridden the waves of Australia's coal boom.

"It's the worst I've seen it in 28 years in the mining industry," says Mr Windle. "Everyone is getting out. Three hundred houses are for sale in my town, three in my street, and rental prices have collapsed on older weatherboard houses from A$1,000 a week to A$200," he says.

Mr Windle was the purchase and compliance manager at Glennies Creek Coal Mine. Earlier this year, however, Brazilian company Vale - which owns the underground mine and an open-cut mine at nearby Camberwell - suddenly announced it was sacking 500 workers and mothballing the mines.

'Sharpening of pencils'

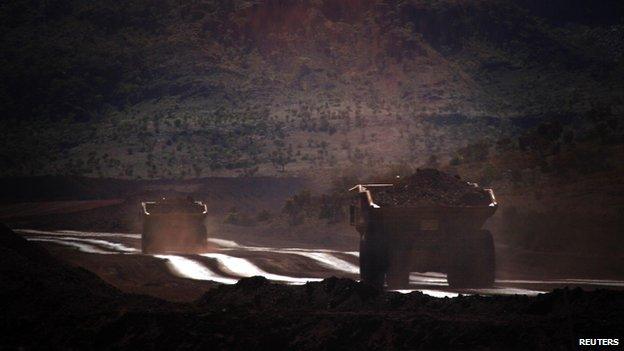

Mr Windle's story is not unusual. Across Australia, coal and iron ore mines are laying off staff, shutting down operations or putting new investments on hold. Resource analysts say it is the end of a long and lucrative mining boom that was mostly fuelled by demand from China.

The number of people employed in coal mining alone rose from 15,000 to 60,000 between 2001 and 2014, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Mining companies offered high wages to entice workers from other industries, and to mines that were often in remote locations such as outback Western Australia.

Preliminary estimates suggest that this year, Australia exported over A$40bn of coal, much of it to China.

But as China's economy has slowed, the price of coal used for power generation has fallen, from US$142 a tonne in January 2011 to US$67 a tonne in November 2014, according to the World Bank.

In the case of iron ore, in mid-December it was trading at about US$70 a tonne, the lowest level since 2009.

The mining downturn has been painful in small towns like Muswellbrook, which has a population of about 10,000 and lies about 250km (155 miles) north of Sydney.

Its locals might find jobs in the region's wine and horse-breeding sectors. But mining has always been the big employer.

Sectors such as wine and tourism can partially compensate for the loss of mining jobs

Muswellbrook mayor Martin Rush says there are still jobs to be found operating local mines but admits the outlook is subdued.

"There has been a 'sharpening of pencils' around the cost side [of mine operations] and a significant reduction in service sector jobs. Contractors were the first to go," he says.

In a bid to offset mining job losses, the town is working closely with the tourism and equine industries, and is planning a Muswellbrook university campus in a partnership with the University of Southern Queensland and vocational education provider, TAFE.

Ripple effect

The fall in the price of coal is a classic case of supply and demand, says senior economist at St George Bank, Janu Chan.

"Over the past decade, prices went up. There was an incentive to increase coal supply, and more mines opened or became profitable. However, as capacity increased, it generated too much coal and prices fell again."

But, she explains, thanks to its own downturn, China started buying less coal and iron ore, adding to a worldwide resources glut.

In just six months, Australia's export earnings from resources have dropped from A$192bn to A$176bn because of lost royalty income and company tax, according to the Australian government's Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics.

China's construction sector is slowing down after years of growth

Federal Treasurer Joe Hockey says the downturn has produced the largest decline in Australia's terms of trade since 1959.

The ripple effect from China's economic slowdown is tinged with irony, says Ms Chan.

"Australia's central bank cut interest rates to 2.5% [in 2013] to compensate for the slowdown in China," she says.

"Effectively, the Chinese housing boom ending means mortgage interest rates fall in Australia, giving a boost to house prices in Sydney and Melbourne [because cheaper credit fuels demand for housing]."

It is poor consolation for Mr Windle, who is now contemplating looking for a job in another state.

"I'm 54 now, and I've had a hip replacement. I might get a job at an outback mine in the far north of Queensland but I'd hate to spend another year working away from home. And suppose they lay off workers too?" he asks.

- Published21 October 2014

- Published23 October 2014

- Published25 August 2013