MH370: Behind the tenacious deep-sea hunt for missing plane

- Published

Jon Donnison on board one of the search ships still looking for the Malaysian Airliner MH370

"You have to believe we'll find something," says Brady Hernandez, a friendly American from Louisiana, in a thick southern drawl. "But will we find something? I hope so. We just don't know."

And there's the bottom line. One year on, despite millions of dollars spent, the greatest aviation mystery in history remains unsolved.

Mr Hernandez appreciates that more than most. As a supervisor on the underwater search team, he's at the forefront of the hunt for MH370.

He's standing on the deck of the Fugro Supporter, one of four ships that have been commissioned to try to find the missing Malaysian airliner.

He looks remarkably fresh for a man who's just returned to port in Perth from seven weeks on the high seas of the Southern Indian Ocean.

"It's not so bad," he smiles with a hint of modesty and a massive dose of understatement.

Brady Hernandez is supervising the underwater search for missing MH370

The search zone is about as remote and bleak as you get - 1,800km (1,100 miles) off the western coast of Australia, it takes six days, full steam ahead, to arrive there by boat.

The Fugro Supporter carries enough fuel to stay at sea for around seven weeks before having to return to port. During their last rotation, the 40-strong crew faced truly appalling conditions.

"The seas were quite large at times and the winds were quite nasty," says Mike Dixon, again with a heavy helping of understatement.

Mr Dixon, a former British Royal Navy seaman from Norfolk, says they had to sail away from two cyclones, with waves as high as 15m (50ft).

"In the rough weather, for the first day it's difficult to sleep," says Mr Dixon. "But after that you become exhausted and then sleep comes," he smiles.

Teams have faced high seas and long spells on the water

'Small target'

The team face a task of an almost unimaginable scale.

The priority search area where satellite data suggests the plane is most likely to have gone down spans some 60,000 sq/km (23,000 sq/miles).

But the underwater search equipment the teams are using can only operate at around walking pace.

So imagine walking around an area 40 times the size of London, looking for something. And then imagine doing it in waters up to 5km deep.

The huge scale of the search for MH370, broken down by Jon Donnison

"It's a very small target in a very large area," says Mr Dixon. "Although a plane looks large when you see it on the ground, when you look at the area we are covering, that plane is pretty small."

And of course when you look on the map, the priority search area is just a tiny sliver of the plane's assumed path across the Southern Indian Ocean.

The data would only have to be slightly wrong for the search ships to be looking in entirely the wrong place.

It's a worry given that so far more than 40% of the priority zone has been covered and nothing has been found. But for the crews on board there's no point in being negative.

"They concluded this was the best place to search for it, so that's what we're here for. Just to see," says Brady Hernandez.

At the beginning Mike Dixon said he had doubts.

"Originally I was uncertain. But I've been given all the information about how the plane was tracked. And given that information I'm confident we're in the right area."

Mike Dixon says he believes the data behind the search is reliable

'Very rugged'

The search ships are working with two key pieces of technology. The first is called a tow fish. The device is lowered into the water on a cable up to 10km long.

It then descends to just above the ocean floor and is dragged along behind the ship. It uses sound waves or sonar to provide a map of the seabed.

The search area has been divided into a grid. The tow fish is dragged slowly up and down in a process the crew refer to as being like "mowing the lawn".

The crew say they've detected several sunken shipping containers but little else.

If the tow fish does detect anything of interest, they can then send down a small unmanned submarine.

The automated underwater vehicle, or AUV, is one of the most hi-tech in the world and cost $10m (£6.5m).

It's equipped with a black-and-white camera as well as sonar and sensors that can pick up traces of oil, fuel or other chemicals in the water.

The crew believe if the plane is down there, it is most likely to have broken up but think it would be sitting proud on the ocean floor and not sunk in.

"The terrain down there is very rugged," says Mike Dixon. "There's ravines, mountains, volcanoes, huge holes. It takes a lot of careful planning when we send the AUV down."

The big fear is not being able to get the AUV, which isn't attached, back on board the ship, which means it can't be used when the weather is really bad.

So far bad conditions have led to several long delays.

The ships are due to finish the current 60,000km search area in May.

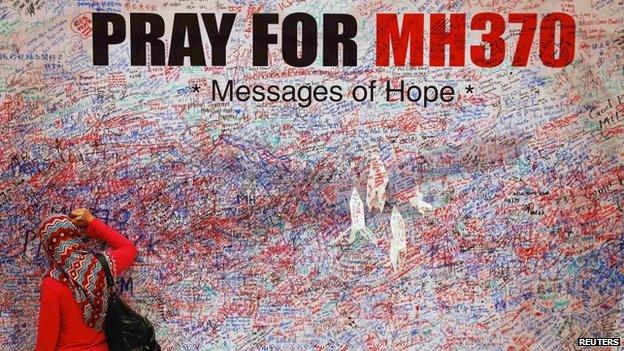

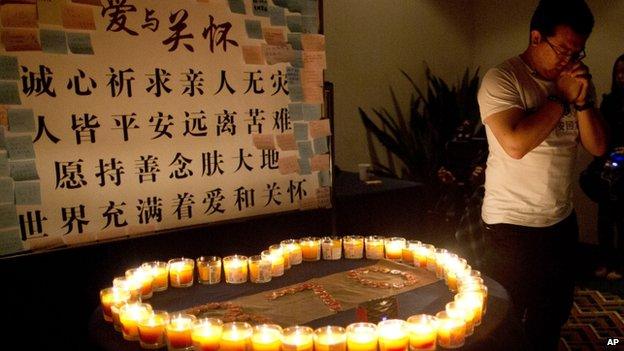

One year on, no fresh information has emerged about the fate of MH370

Relatives of those on board want answers to their questions about their loved ones

'Found the haystack'

Nobody's prepared to go into too much detail about what will happen then if MH370 hasn't been found.

"That's a decision for the politicians," says Martin Dolan, chief commissioner for the Australian Transport Safety Bureau.

"They're the ones that direct taxpayers funds to us. We'll just provide technical advice into that decision-making process."

Martin Dolan, chief commissioner of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, is "cautiously optimistic" his team will find the plane

The search is currently being jointly funded by the Australian and the Malaysian governments.

One Fugro official told me he believed when the current search zone was finished, his teams would just be asked to move into the next most likely search area.

Yet Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott this week hinted at the possibility the operation may be scaled back, saying he couldn't guarantee it would go on at the same intensity forever.

Despite the lack of success so far, Martin Dolan says he remains cautiously optimistic.

"We think we've found the haystack. We just need to find the needle," he says at his headquarters in Canberra. "We can't give a 100% guarantee but we're certainly giving it our best shot."

And for the crew on board the Fugro Supporter, they say they owe it to the families of the passengers on board MH370 to continue the search.

"It's very important task that we're trying to do," says Mike Dixon. "We're trying to bring closure for the families. To find an answer for them."

Before I say farewell to Brady Hernandez I ask him what he'll be doing now he's back on dry land. I suggest a cold beer might be in order (the ship is an alcohol free zone).

"No, I'm heading back tomorrow," he replies. I assume he means back to Louisiana where his wife and kids are waiting.

"No," he says. "I'm heading straight back into the Indian Ocean for another seven week stint. I just want to find this plane."