Australia's remote indigenous communities fear closure

- Published

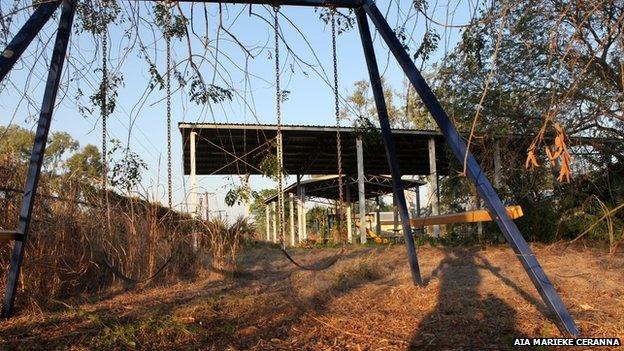

The closure of the Oombulgurri community in Western Australia has left it a ghost town

Derby Aboriginal elder Lorna Hudson was a child when government authorities in the 1960s moved her people from tiny Sunday Island off the remote north-west coast of Western Australia to the mainland.

For a time most of the Sunday Island "saltwater" people lived on a reserve in the outback town of Derby, recalls Ms Hudson.

Later many moved to the coastal community of One Arm Point, 200km north of the resort town of Broome, where they resumed traditional hunting and fishing.

Their dislocation is an experience shared by many Indigenous Australians who were forced off their land, last century, either because of changes in government policy or lack of employment.

"That's how people lost their culture," says Ms Hudson. "It put us in a different environment, away from our country."

In the wake of plans by the West Australian government to close many small indigenous communities, the people of One Arm Point and other remote indigenous communities fear history might soon be repeated.

Comments earlier this week, external by Prime Minister Tony Abbott that people had made a "lifestyle choice" to live in these communities have intensified local fears people will be forced out of their homes, many of which are on ancestral land.

Western Australian Premier Colin Barnett last year announced that up to 150 of the state's estimated 250 remote indigenous communities might be closed.

Delia Clarke, a former resident of Oombulgurri has now moved to Wyndham

His government had accepted an offer from the federal government to assume responsibility for the communities in return for A$90m ($68m, £46m) in funding but then decided it did not have enough money to keep them all open.

The state government says many of these communities - some with as few as five people and few facilities or infrastructure - are not financially viable. It estimates that in one case it is spending A$85,000 per person per year on essential services such as power and running water.

Indigenous leaders say there has been no formal evaluation by the government of the costs and no consultation with the people who live there about what they need or expect.

The premier also says there is a darker shadow hanging over some of the communities: levels of abuse and neglect of children that are "a disgrace to this state".

'Really creepy'

Similar concerns led to the controversial closure over a couple of years of the Oombulgurri community in the eastern Kimberley region of Western Australia.

A coronial inquiry found the township to be in a state of crisis, with high rates of suicide, sexual abuse, child neglect and domestic violence.

Services including power and water were shut off in Oombulgurri

But many of the people living in Oombulgurri didn't want to leave, says Amnesty International's Australian Indigenous Peoples' Rights Manager, Tammy Solonec.

As the government gradually closed vital facilities such as the health clinic, school and police station, and eventually shut off the town's power and water, people were left with no choice but to move out, says Ms Solonec.

When she visited the town last September there was a ghostly atmosphere of abandonment.

Children's drawings were still pinned to school walls, family photos were inside some of the houses, clothes were lying on the ground.

"It was really creepy," recalls Ms Solonec. "There was a suitcase just sitting in the middle of the road... and there were wild horses running around.

"There were clear signs people were not given time to retrieve their belongings before they left. And now they are gone it's almost impossible to come back."

Only wild horses are now left in the remote town of Oombulgurri

Many of Oombulgurri's residents moved to the town of Wyndham, putting pressure on that town's services and infrastructure, a ripple affect Amnesty International and others say could be seen across the Kimberley if more communities are closed down.

Kimberley Land Council Chief Executive Officer Nolan Hunter says Mr Abbott's comments, and the move to close communities, contradict the whole point of native title, which recognises the rights and interests of indigenous people to land and waters according to their traditional laws and customs.

"It's inconsistent with all the commitments Australia has made to indigenous people, especially native title's acknowledgement of cultural connection to the land and people's right to be there," he says.

Mr Abbott's key indigenous advisor Warren Mundine concedes communities have to be realistic about how much government money is spent on isolated communities.

But he says government has to understand that for indigenous people "their country is the essence of their being so that's why they live in these areas".

Repeat of history

Former Liberal Aboriginal Affairs Minister Fred Chaney agrees that the viability of communities needs to be examined but he says there is an element of hypocrisy when one considers the many subsidies paid to non-Indigenous Australians living in remote areas.

"On that sort of measure, [the Northern Territory city of] Darwin is not sustainable," he recently told ABC TV.

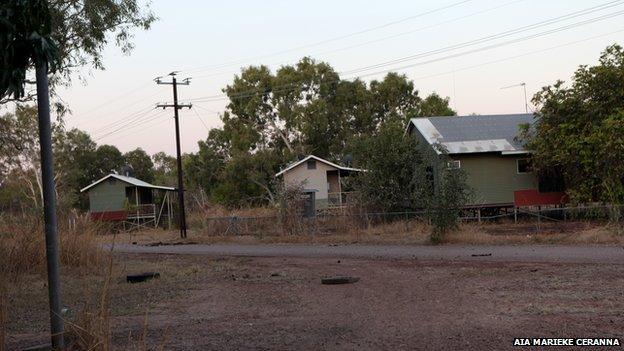

Indigenous communities are now waiting to hear which areas might be next to be closed

He warns the closures could be "catastrophic" if Western Australia repeats the mistakes of the 1960s when indigenous people were left to flounder on the outskirts of outback towns when they were kicked off pastoral lands after being granted the right to equal pay.

Organisations representing 35 communities around the small Kimberley town of Fitzroy Crossing say Western Australia's closure plans are "the latest and most dramatic twist in what has felt like a war of attrition against our communities".

"We assert the right of people to live in and on their traditional country, for which they have ancient and deep responsibilities. To be talking of relocating people off their traditional country does indeed take us back 50 years in a very ugly way," they said in a statement. "Do not turn our people into fringe dwellers once again."

Back at One Arm Point, home to about 400 people, culture "begins and ends on the land and with the sea", says community leader Dean Gooda.

Mr Gooda says its residents, like those in indigenous communities across Western Australia, are anxious about the future, with no official word on which communities will close and under what criteria.

"It would be tragic for them to have to move off," he says.

"It doesn't matter who you are. If you're an Australian, you should be afforded essential services like everyone else. That's all we are asking for, the same services that mainstream Australians are afforded as a right, as a given, as a matter of course."

- Published11 March 2015