Australian campaign to abolish death penalty

- Published

Australian opposition to the death penalty is growing in the wake of the Bali Nine executions

Momentum is gathering in Australia to push for the elimination of the death penalty around the world but some say Australians should address attitudes in their own backyard first.

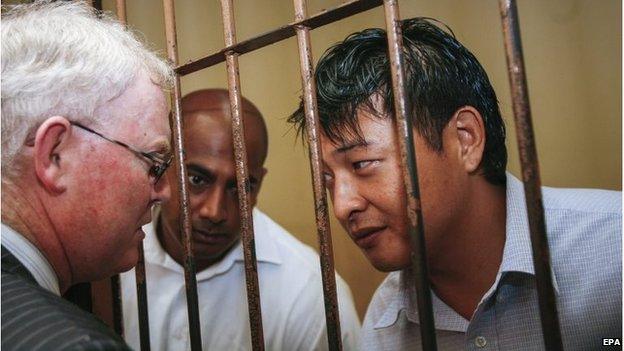

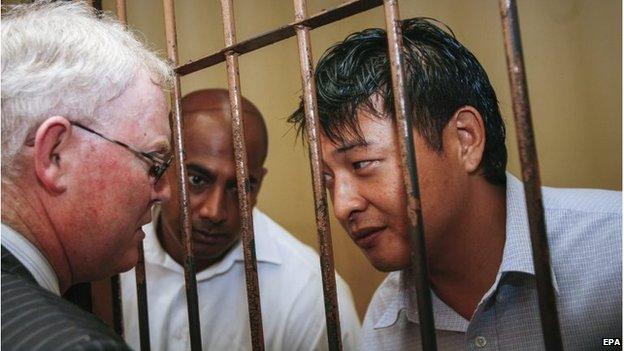

Not long before they died, convicted drug traffickers Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran expressed a wish for a global campaign to abolish the death penalty.

They had spent 10 long years in Indonesian prisons after being convicted in 2006 of playing a major role in the so-called Bali Nine drug ring that attempted to smuggle more than 18lb (8.2kg) of heroin from Indonesia to Australia.

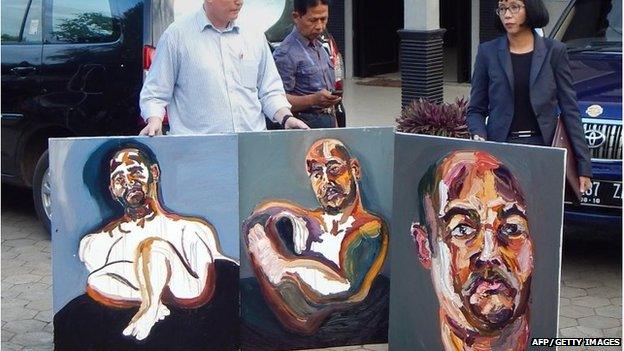

By all accounts, they had worked hard to rehabilitate themselves: Chan had qualified as a pastor and ministered to fellow inmates. Sukumaran found solace in art. His talent for painting earned him an associate degree in fine arts from Western Australia's Curtin University two months before his execution.

Those changes slowly won them the sympathy of many Australians. Now, their desire to see more action on the death penalty is being taken up by some of the country's top politicians.

Front foot

Devastated by the failure of frantic diplomatic and legal bids to save their lives, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop last week said "it is time for us to have a significant discussion about the application of the death penalty for drug offences in our region".

Foreign Minister Julie Bishop worked hard for clemency for the Bali Nine duo

Former Attorney General Philip Ruddock has taken the campaign a step further. He has written to the local diplomats of countries such as Brazil, France and Nigeria, whose nationals were executed this year by Indonesia or are on death row there.

Co-chair of Australian Parliamentarians against the Death Penalty, Mr Ruddock wants them to work with Australia on abolishing the death penalty in and beyond the region, including in the United States.

"I think it is timely that Australia indicates it has a principled position on this matter and that we're prepared to be on the front foot in advocating change," Mr Ruddock told the BBC.

But Agriculture Minister Barnaby Joyce, who is charged with managing sensitive trade issues with Indonesia, says Australia might have to look into its own backyard as well as trying to influence others.

"I have to be honest, I do get approached by people saying, 'Well, that might be your view, Barnaby, that you don't support the death penalty, but it's not our view'," he told ABC television.

"And I find that rather startling at times and I think that the discussion that we're having about others, we should also be carrying out domestically."

Many Australians wanted the Indonesians responsible for the 2002 Bali bombings executed

Australia has a long-standing bipartisan opposition to capital punishment and has not executed anyone since 1967.

But the nation's leaders at times send mixed messages about the death penalty. Comments by former Prime Minister John Howard in 2007 about the ringleaders of the 2002 Bali bombings, which killed 202 people, are a prime example.

"The idea that we would plead for the deferral of executions of people who murdered 88 Australians is distasteful to the entire community," he said.

However, Australians' acceptance of the use of the death penalty by other countries has fallen in recent years.

A 1986 poll found more than 70% believed it should be carried out if Australians were sentenced to death in another country, says Lowy Institute for International Policy polling director Alex Oliver.

But a Lowy poll conducted in February this year showed nearly a complete reversal: 62% of people did not want Chan and Sukumaran to be executed, and nearly 70% believed the death penalty should not be used to punish drug traffickers.

Another poll, in 2010, found that nearly 60% of people wanted Australia to push for abolition of the death penalty in South East Asia. Ms Oliver expects to see similar sentiments in a poll conducted at the weekend about the latest executions, to be published later this week.

"The last 35 years have seen a strengthening opposition to the death penalty generally," she says.

However, she says views can change depending on who is facing capital punishment and what their crime is.

Most people hold inconsistent views on the death penalty, says Patrick Stokes, Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at Melbourne's Deakin University.

'Accusations of hypocrisy'

"Most people don't like the death penalty but think maybe certain people should be put to death, or they don't want the death penalty here but are less concerned about overseas, or they don't like the thought of Australians being executed, say, in China or Malaysia or Indonesia but are not concerned about it being applied in places like the US, or Iran or Japan or Saudi Arabia," he says.

Sympathy for Chan and Sukumaran grew after the media drew attention to their rehabilitation

"It's an area where most people don't have a clear, principled position but a fragmented reaction to cases as they arrive."

Working harder to abolish the death penalty rather than just winning a reprieve for sentenced Australians would shield Australia from accusations of hypocrisy or "special pleading", says Lowy executive director Dr Michael Fullilove.

Asia is the obvious place for Australia to begin - it is home to "the world's worst offenders" on capital punishment, like China. Mr Fullilove says Australia should forge a regional alliance with countries in the region that have abolished the death penalty: Cambodia, Nepal, East Timor, Bhutan and the Philippines. It should also make the issue not just a principle, but a priority.

"We should aim to become a leader in the international movement against the death penalty," he says.

- Published4 May 2015

- Published30 April 2015

- Published29 April 2015