Indigenous Australia exhibition tells many stories

- Published

Stories are told through old and new Indigenous art such as this 'Kungkarangkalpa' painting

It is just past 8 a.m. on a chilly London morning and the gates of the British Museum have yet to open. An enormous exhibition banner flaps gently in the breeze as a small group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women crane their necks upwards to read the words: 'Indigenous Australia: enduring civilization'.

The long awaited exhibition, some six years in the making, has just opened and the group, including Simon Hogan, a senior man and artist of the Spinifex people who is now well into his 80s, is here to see the show.

Yolngu men Wukun Wanambi and Ishmael Marika help conduct a ceremonial welcome to re-connect the artefacts with their people.

As the sound of a yidaki (didgeridoo) and Aboriginal song fill Gallery 35, there are wide smiles and teary eyes.

For Gaye Sculthorpe, the exhibition's curator, it is a significant and moving moment.

Imperial legacy

Ms Sculthorpe, of Tasmanian Aboriginal ancestry and now curator of the British Museum's Oceania collection, is at the heart of a newly ignited debate on the institution's imperial legacy and the vexed "ownership", provenance and possible future repatriation of key objects in the 6,000-piece collection.

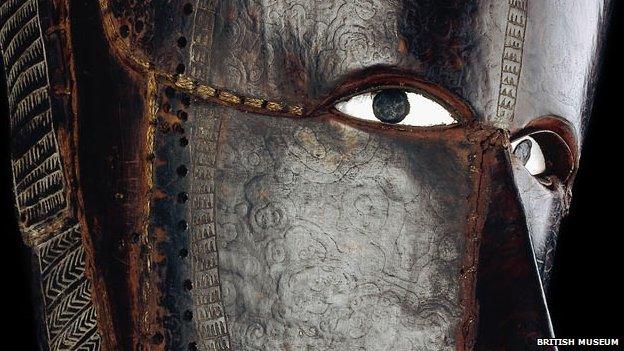

Ceremonies involving masks were a key part of traditional life in the Torres Strait islands

Aboriginal advocates in Australia have focused on this issue, raising the possibility of a re-run of the 2004 Australian legal challenge to return bark objects loaned by the British Museum to Museum Victoria.

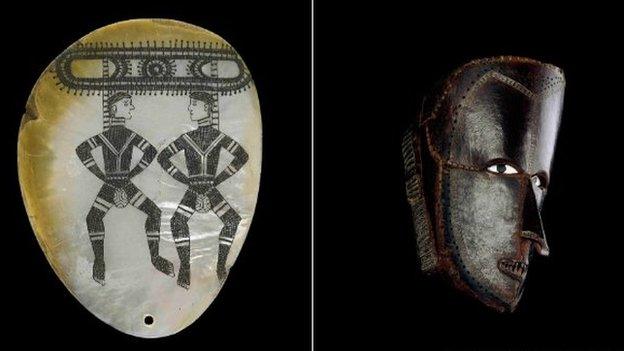

The exhibition contains some of the earliest objects collected from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by British colonists and missionaries after 1770.

Some objects hark back to 'first contact' with the Australians

Most have never been seen in public before. They tell the dual stories of a 60,000-year-old, living culture and the struggle to survive colonisation, along with the contemporary role of museums holding such collections.

A scholar, activist and curator for more than three decades, Ms Sculthorpe is no stranger to such controversies, having helped develop policy during the earliest negotiations in the 1990s on the repatriation of human remains to Aboriginal communities in the Australian state of Victoria.

Speaking with the BBC just 24 hours before the ceremony, Ms Sculthorpe is pensive but exudes a quiet confidence.

"For me, it is the Indigenous voices that come through that are so important. You can see that when they visit - listen to them, hear what they say," she says.

The exhibition is the product of an extraordinary, behind-the-scenes project that has seen Ms Sculthorpe and her team open the British Museum's stores and collections to scores of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander visitors who have come looking for artefacts and objects significant to them.

Permanent display

Launched in 2011 as part of a research collaboration with the National Museum of Australia and the Australian National University, the project has offered Indigenous communities access to important parts of the museum collections. It aims to help them reconnect with significant traditional objects and add to local knowledge, while also helping to improve the museum's own understanding and documentation.

The project is particularly important in light of a recent announcement by the museum's Director, Neil MacGregor, that there may be a permanent Indigenous display at the British Museum.

"We have had many people who come to look at an object from their area: to be with it is an emotional experience for those individuals and to be there at the moment of sharing that first view is very special", says Ms Sculthorpe.

Ishmael Marika, a 24-year-old Yolngu man from north-east Arnhem Land is in London with the Indigenous delegation. A film-maker at Buku-Larrnnggay Mulka art centre in Yirrkala, he is working to try to digitise the complexity and richness of the Yolngu culture. Already, hundreds of thousands of photos, video, audio files and early stills have been archived as part of the project known as Mulka, or "keeping things safe".

Ishmael Marika, a Yolngu man from north-east Arnhem Land, has been helping the museum categorise pieces in the collection

Kade McDonald, art co-ordinator for the centre, remembers Mr Marika in the collection stores of the museum, surrounded by artefacts including an ancient yidaki. "Everyone had curators' white gloves on looking at objects but Ishmael just picked it up and started to play it. That is what it was for him, completely natural, to be used, alive. It was quite a moment".

Collecting continues

Ms Sculthorpe says people are often surprised to learn the museum is still collecting.

"Documenting contemporary Aboriginal values and beliefs is also ongoing. People might make generalisations, talk about 6,000 objects being returned, but we have been buying from artists and from art centres to continue to develop the collection and we want to develop it even further.

"I think it is important to help people who make decisions about the objects - where they are held and what should be displayed - aware of all the information relevant to making those decisions.

"For me, it's really important to do what I can to encourage greater engagement of Indigenous people in the collection and the value of doing so, and the way it is done demonstrates the broader significance of this material."

The exhibition is open until 2 August and many of the objects will travel to Australia for a related exhibition at the National Museum in November.

- Published27 February 2015