Australian women not to blame for family violence – campaigner

- Published

Surveys show many Australians still blame women for violence perpetrated by men

Last September, Geoff Hunt murdered his wife and three children on their New South Wales farm and then killed himself.

The 44-year-old farmer shot his three children - Fletcher, 10, Mia, 8, and Phoebe, 6 - inside the family home near Lockhart, 80km south of Wagga Wagga. He killed his wife, Kim, on a path at the back of the house.

Locals were horrified but quickly attributed Hunt's violence to the stress of farm life and the strain on the family from injuries Kim sustained in a car accident two years earlier.

Rumours swept the town suggesting Kim - who had a brain injury, dragged one foot and did not have the full use of one of her arms - could have committed the murders.

Newspaper headlines described five deaths instead of four murders and one suicide, and media reports quoted neighbours, friends and family describing Hunt as a nice man who loved his family.

But nice men who love their families do not murder them, says Rosie Batty.

Damaging narrative

This year's Australian of the Year and an articulate campaigner against domestic violence says we must stop making excuses for the perpetrators and stop blaming the victims.

Rosie Batty is changing the debate in Australia about domestic violence

In a powerful speech delivered on Wednesday to the National Press Club in Canberra, Ms Batty - herself a victim of domestic violence - said what many others have not: Australia suffers from a "misguided and damaging narrative that ultimately lets perpetrators off the hook".

A woman is killed in Australia almost every week by a partner or ex-partner.

Violence against women and their children cost the Australian economy A$14.7bn ($11.5bn; £7.5bn) in 2013.

More than half of people believe that a woman could leave a violent relationship if she really wanted to.

Statistics from Domestic Violence Victoria

"'Why didn't she take her children out of such a violent situation?', 'She was wearing headphones', or 'She was drunk and out late on her own' are just some of the assertions that blame survivors for the violence inflicted upon them," Ms Batty told a room of journalists as she launched a national media awards scheme to recognise exemplary reporting of violence against women.

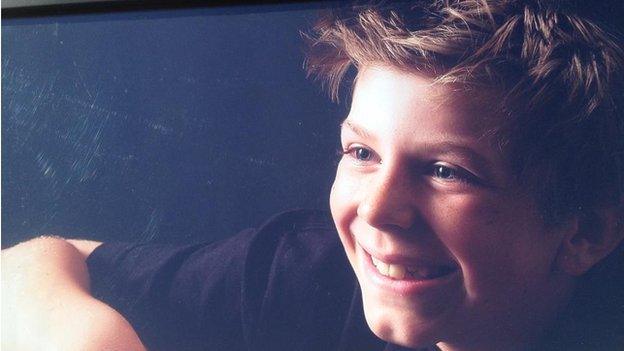

In February, last year, her 11-year-old son Luke was beaten with a cricket bat and then stabbed to death by his father, Greg Anderson, at a cricket training session in rural Victoria. Police shot dead Anderson at the scene.

Luke Batty's father was known to police for violence towards his family

Since then, Ms Batty has emerged as a powerful advocate for the rights of women and children at risk and has sparked a national debate about public attitudes to domestic violence and the lack of government support for the victims.

Media's influence

In January, Prime Minister Tony Abbott said domestic violence was the most urgent matter for state and federal governments to tackle and called for agreement on a national domestic violence order scheme that would protect victims who fled interstate from their attackers. Mr Abbott also appointed Ms Batty to a panel advising governments on family violence.

Ms Batty says her experience with the media has been mostly positive but she says the way the Hunt murders were reported shows many people still blame women while making excuses for the violent behaviour of men.

Research suggests news coverage influences both public policy and public opinion on topics such as gender-based violence.

Rosie Batty wants Prime Minister Tony Abbott to do more about domestic violence

"The media isn't just telling my story. It is telling the story of one in six women in Australia who are affected by intimate partner violence," says Ms Batty.

"It's telling the story of the children who witness this violence, as more than half of these women had children in their care when the violence occurred."

Family 'terrorism'

Family violence has always been a part of Australian life but for a long time no one wanted to talk about it, she says.

She has called for a bipartisan approach to the issue, substantial investment in long-term strategies, re-instatement of funding cut from frontline services, and the removal of means-testing for women seeking advice at community legal centres.

Ms Batty says it is amazing that at a time when it has been threatening to cut spending across the board, the federal government has not baulked at funding new counter-terrorism projects.

"So, let's start calling it family terrorism and perhaps we start to see that investment of funding being applied where it needs to be," she says, noting the very high number of Australian women who suffer violence at the hands, not of terrorists, but of the men in their lives.

"If you have three sisters or three daughters, one of them will encounter violence. If you work with at least six women, one of them has experienced violence by a current or former partner."

Ms Batty also wants the judicial system to stop giving men who have beaten or killed their partners regular access to their children. Courts should also give media permission to write about more of the cases that come before them. [Rules vary, but most Australian courts have strict rules about reporting anything that might identify a child connected to a case.]

Australians needing support or advice about family violence can call 1800 737 732

- Published25 January 2015

- Published5 December 2014

- Published20 October 2014