The story behind Australia's most notorious militant

- Published

Sharrouf was the most notorious of the many Australians fighting with IS

The story of Khaled Sharrouf, one of at least 120 Australians thought to have been fighting with Islamic State in the Middle East, may have come to an end.

The Australian government is trying to verify reports that he has been killed in Syria, along with his friend, Sydney man Mohamed Elomar.

Khaled Sharrouf turned up at Sydney airport in December 2013 with his brother's passport and a plane ticket that would get him out of the country.

Despite being on a security watch list, it took less than two minutes for the convicted militant to clear checkpoints before boarding a plane for Syria to join Islamic State (IS).

Since then, the high school drop-out with a history of petty crime, drug use and mental illness has become the most recognisable of a band of Australian Islamic jihadists fighting in the Middle East.

Australia wants to strip citizenship from dual nationals who fight for IS

The two men are among at least 120 Australian citizens the government believes have been fighting with the militant group in the Middle East. The government suspects another 160 are supporting IS in Australia.

Horrific photos

Reports of the deaths of the two Sydney men come as the government prepares to table legislation that will strip dual Australian nationals involved with terrorism of their Australian Citizenship.

Convicted some years ago for his role in a terror plot involving targets in Sydney and Melbourne, Sharrouf only came to the public's attention after a series of horrific photos were posted on social media, last year.

The photos showed Sharrouf and Mr Elomar holding up what was described as the severed heads of pro-Syrian government fighters.

One of the photos showed Sharrouf's seven-year-old son holding up a head.

Karen Nettleton, the mother of Sharrouf's wife Tara Nettleton, said in a statement released to the media on Tuesday that a "messenger" had told her that Mr Elomar was dead and her son-in-law was missing and presumed dead.

Terror plot

Syria is a long way from Western Sydney and Sharrouf's troubled early life, but it became a beacon for the father of five.

He was sentenced to four years in prison in 2009 for his role in the 2005 terror plot.

He had been arrested with several others in what was then the largest anti-terror raid in Australian history, code named Operation Pendennis by police.

The conflict in Syria has devastated many towns and cities

As part of that investigation, a conversation between Sharrouf and another person was intercepted by police on 21 October 2004, according to court documents. The two men were discussing a television programme they had seen on terrorism.

"Let the people accept that we're this, but we're doing it for a proper cause, you know," Sharrouf told his associate.

Bungled shoplifting

Born in Australia in 1981 to Lebanese migrants, Sharrouf was convicted after he tried to steal about 132 batteries and six digital alarm clocks from a Big W store in Sydney's western suburbs. Authorities claimed the stolen goods were to be used in homemade bombs.

His bungled shoplifting - according to court documents he ran away when stopped at the register, with "batteries falling from his pockets" - belied a much more violent character.

Expelled from high school in his mid-teens for attacking another student, he began heavily using LSD, ecstasy and amphetamines, while suffering from severe, chronic schizophrenia that may have influenced his eventual radicalisation.

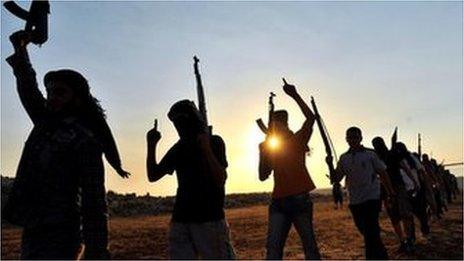

Australian police have conducted numerous raids against alleged Islamic militants

"He soon took up drugs and became involved in petty criminality and it seems that part of the people he started to mix with introduced to him a very extreme form of radical Islamic religion," former Supreme Court justice Anthony Whealy told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). Mr Whealy presided over the Pendennis terrorism trials.

Physical abuse

Sharrouf had a tough childhood, according to psychiatrist Dr Olav Nielssen.

"He was subjected to physical abuse by his father and was affected by his father's desertion of the family during his early teenage years," Dr Nielssen wrote in a 2008 report for the New South Wales Supreme Court.

"There was a history of substance abuse in adolescence that may have contributed to the onset of mental illness," Dr Nielssen said.

At the time of his arrest, Sharrouf was living with his wife Tara and receiving a disability pension from the government. He had worked on and off as a labourer on construction sites but gave that up as a result of his mental illness.

The pair met when they were students at Chester Hill High in Sydney's western suburbs, according to local media reports. Ms Nettleton converted to Islam after her husband re-embraced his family's religion in an attempt to turn his life around.

Battlefield commander

Released from jail in 2009, Sharrouf began attending the notorious Sydney Al-Risalah prayer centre run by Wissam Haddad. Mr Haddad and Sharrouf soon became friends.

Mr Haddad told ABC that Sharrouf was fulfilling a long-held wish to fight for Islam when he snuck out of Australia in 2013.

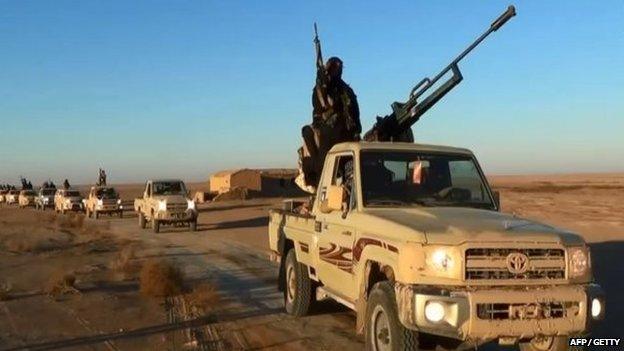

The United Nations has accused IS of waging a campaign of terror in parts of Syria

"He never wants to come back. He wants nothing to do with Australia," said Mr Haddad.

"He's happy doing what he is and he's hoping to be granted that gift from God to die as a martyr."

In Syria, Sharrouf reportedly worked as a low-level IS battlefield commander. Before this week's reports, there had been other brushes with death, such as when he survived a rocket attack on his car several months ago.

In her media statement, Karen Nettleton said family friends inside Sharrouf's car, "including a mother and children" were killed.

At some stage, Sharrouf's wife and children joined him in Syria, and his daughter, now aged 14, married Mr Elomar.

According to her mother, Ms Nettleton and her five children fear for their lives, and want to return to Australia.

"My daughter made the mistake of a lifetime," said Ms Nettleton senior.

"Today she is a parent alone in a foreign and vicious land looking after a widowed 14-year-old and four other young children. They want to come home."

Australian Immigration Minister Peter Dutton said on Wednesday the family should contact the Australian authorities rather than speak to the media.

- Published23 June 2015

- Published11 August 2014

- Published27 May 2015

- Published12 March 2015