Australia accused of creating second class of citizens

- Published

Karen Nettleton and her daughter Tara in happier times

The Australian government says new citizenship laws will help combat terrorism but experts worry too many people will be affected by the laws, including children.

A few days ago, Sydney woman Karen Nettleton received the knock on her door she had been dreading.

She was told her granddaughter's husband was dead and her daughter's husband was missing, presumed dead.

The Australian government is now trying to verify the deaths of the two Australian men, Mohamed Elomar and Khaled Sharrouf, who left the country two years ago to join the Islamic State (IS) group in Syria and Iraq.

The second-generation Lebanese migrants, born in Australia, shot to notoriety when they posted photos of themselves on social media holding up what were described as severed heads of pro-Syrian government fighters.

'Collateral damage'

One of the photos showed Sharrouf's seven-year-old son holding up a head.

Sharrouf is a convicted terrorist who married Mrs Nettleton's daughter Tara. She and her five children followed Sharrouf to Syria.

Elomar, Sharrouf's friend and boxing partner, is married to Sharrouf's 14-year old daughter.

In a media statement, Mrs Nettleton said she did not want her family "to be collateral damage in this shameful and tragic war".

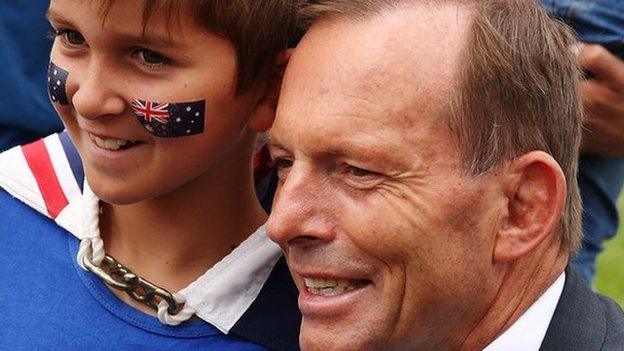

The government has been accused of unfairly targeting citizens with dual nationality

But it is too late for that. Their story has become part of a wider debate about whether Australians who support IS in any way should forfeit their citizenship.

The Australian government thinks they should and this week introduced a bill, external into parliament that will strip dual nationals convicted of or suspected of being involved with terrorism of their citizenship.

The Labor opposition is expected to support the bill.

One problem, says University of Sydney law professor Anne Twomey, is the kinds of people the bill targets.

New frontier

Prof Twomey says the government is suggesting the bill is all about protecting the nation from Australians who were born in another country leaving to fight with overseas terrorist groups.

"But it could include Australians born and bred here but who, for some reason, have citizenship of another country," she told the BBC.

And the categories of conduct that could strip someone of their citizenship "can cover all sorts of things", she says.

"It can involve things that have little relation to those that we traditionally think of as terrorism, for example damaging Commonwealth property or committing a violent act with an ideological motive."

Immigration Minister Peter Dutton says terrorists could damage government assets

Tim Vines, a lawyer and vice-president of Civil Liberties Australia, agrees.

"It is a brand new frontier of stripping citizenship as a punishment," says Mr Vines.

Unconstitutional?

Immigration Minister Peter Dutton has said a parliamentary committee will consider some of these concerns.

"But the advice from the agencies is that government assets, police, all of these, terrorists would seek to do harm to those people, to those assets," he said.

The government had originally proposed giving the immigration minister the power to decide who should lose their citizenship.

When it was pointed out this would be unconstitutional as only the judiciary has this power, it drafted a bill that says a person "self-executes" the loss of their citizenship by conducting certain acts.

However, by making it a matter for legislation, judicial power has shifted to the parliament, which may also be unconstitutional, says Mr Vines.

There are other problems.

"There are now two classes of Australians. Sole Australian citizens [born here and who have no other citizenship] who are special, who are more Australian compared with those Australians who have dual citizenship."

The relationship between the state and its citizens is changing

The Citizenship Act already allows children to lose their citizenship in certain circumstances, for example, if their parents lose it.

Exporting terrorists

However, Mr Vines says because many more adults will now be caught up in the law - some of whom will be parents - the potential number of children who will be affected is larger.

The bill also changes the relationship between the government and a citizen, he says.

"I think morally if we have accepted someone's application to be a citizen and there is a compact between the government and that person... the state has a responsibility to look after and punish a citizen rather than exporting the problem."

The bill is silent on how people can challenge the loss of citizenship in the courts; it does not outline what happens if someone's conviction for terrorism is overturned, and it says nothing about who finds out about a person engaging in the kind of conduct proscribed by the Act.

Who in government will determine that the relevant conduct has occurred, asks University of Sydney law lecturers Rayner Thwaites and Emily Crawford.

Mr Abbott has not indicated any special efforts will be made to help the Nettleton family

"A minister? A bureaucrat subject to ministerial pressure? And what is the process by which that determination will be made?" they wrote in an article for The Conversation.

They noted that all the government needs to strip someone of their citizenship is the kind of low level information that can be used to refuse someone a visa.

The government estimates about half of the 120 Australians fighting with IS in the Middle East are dual nationals. Many other dual nationals are suspected of supporting terrorism from inside Australia.

Ironically, Tara Nettleton and her children are not dual citizens and it appears neither are Sharrouf and Elomar. The new bill would not have stripped them of their Australian citizenship.

Karen Nettleton says her daughter Tara "made the mistake of a lifetime" by leaving the country and has begged Prime Minister Tony Abbott for help.

"They want to come home," she says.

- Published23 June 2015

- Published24 June 2015

- Published27 May 2015