Sunflower mementoes for the families of MH17 victims

- Published

The sunflowers at the crash site have taken on special symbolism

When she stood on the scorched earth where the plane wreckage lay, in a field surrounded by sunflowers, Angela Rudhart-Dyczynski fulfilled a promise she had made to visit the place where she lost her daughter in the crash of MH17.

Fatima Dyczynski, 25, described as a "bright" and "ambitious" aerospace engineer, had been working in the Netherlands, a long way from her family.

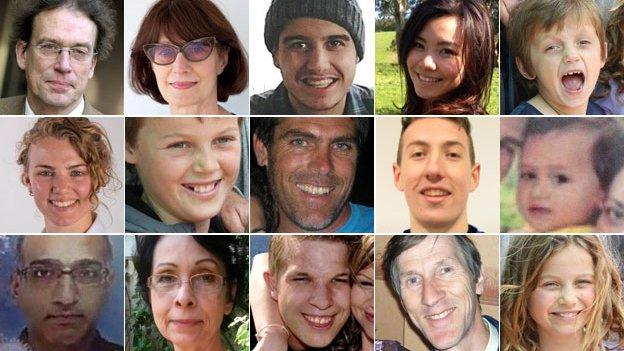

Making her way home to see her parents in Australia, she was one of 298 victims killed when the Malaysia Airlines flight from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur was shot down on 17 July last year.

Ten days later, her parents, Angela and Jerzy Dyczynski, were the first relatives of the 38 Australian victims to arrive at the crash site in eastern Ukraine, ignoring the Australian Government's travel warnings.

As they flew back to Perth in Western Australia, facing the incomprehensible reality that their daughter would not be coming home, the Dyczynskis clutched a small, symbolic keepsake from the crash site: a bag of sunflower seeds.

Year-long mission

When they landed, Australian Customs made the heartbreaking decision to confiscate the seeds because of the island nation's strict quarantine laws.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, Australian journalist Paul McGeough and photographer Kate Geraghty were still at the scene of the crash, and hatching a plan to import some of the sunflower seeds from the site.

The "bobbing" sunflowers gave journalist Paul McGeough (left) the idea for the project

They wanted to give the families back home a tangible connection to the foreign resting place of the Australian victims.

It was a year-long mission that saw a batch of seeds cross three continents to arrive at a bio-security compound in Melbourne.

In a phone interview from his base in Washington DC, Mr McGeough, chief correspondent for Fairfax Media, told the BBC he had expected some issues with Australian quarantine.

Proof of life - a seed germinates in cotton wool on McGeough's windowsill

What he did not anticipate was the lengths staff in Australia's Agriculture Department would go to - literally - bring the project to life.

Last December, he wrote about the sunflower project in a Fairfax newspaper column in the hope of reaching out to relatives.

"It is quite a decision to make about how you intrude on the grief of people after a disaster such as this," Mr McGeough said.

Plant pathologist Mark Whattam (left) shows the seeds to his colleagues Darryl Barbour and Nicola Hinder

Department of Agriculture official Nicola Hinder contacted the seasoned war correspondent after she read the story and talked to him about the risks of bringing foreign seeds into the country.

Journalists Geraghty and McGeough covered the story of the downed MH17 plane

For various reasons, sunflower seeds are deemed high risk imports.

Mr McGeough was cautious about trusting Ms Hinder - whom he has since dubbed the Quarantine Queen - but he now says he and Ms Geraghty "could not have done it without her".

When the seeds arrived in Canberra, Ms Hinder and her team set about cultivating sunflower plants in a secure quarantine facility.

In turn, those plants generated a new batch of seeds. If those seeds were free of pests and disease they could be safely distributed to the families.

Sunflower plants were grown in Australia from the seeds collected from the crash site

And so it turned out.

By March this year, the plants had grown to about 1.5m (5ft) and by June there were enough high-quality seeds to fill 200 packets.

Mr McGeough said the Dyczynskis were "ecstatic" to learn the seeds had finally been cleared for delivery.

Harvested by hand, seeds from the crash site are packed for transport to Australia

He described the symbolism of the sunflower in the face of the devastation wreaked by the crash on so many people.

"All these nodding heads in a field hiding below what is an abomination, much of the bodies and possessions obscured beneath a comforting blanket of sunflower heads," he said.

Ms Hinder credits many people for the project's success.

"There are a lot of unsung heroes along the way," she told the BBC, adding that her entire department felt "immense pride" that they were entrusted with handling the seeds and to be able to help bring a memento to the loved ones and relatives.

The extended Dyczynski family plant sunflower seeds in memory of Fatima

Photojournalist Kate Geraghty saw firsthand how much the second-generation seeds meant for families like the Dyczynskis.

She recently watched the West Australians plant a seed for their daughter at a friend's orchard where Fatima stayed when she first arrived in Australia as a teenager.

"Angela (Fatima's mother) was in tears, as was I," Ms Geraghty said.

Relatives and friends of all of the 38 Australian victims have contacted the two journalists asking for some of the seeds and dozens more requests have come from abroad.

Fairfax Media's "Planting Hope", external multimedia tells the full story.

- Published25 July 2014

- Published26 February 2020

- Published28 July 2014