Australia refugees: Detention centre 'gag' angers medics

- Published

Australian laws forbidding people working in the country's detention centres from speaking out about what they see have raised grave concerns in the medical community.

When Peter Young was in charge of mental health services at Australia's refugee detention centres, he says it became increasingly clear that authorities wanted to "keep the lid" on health issues that asylum seekers were experiencing.

The senior Australian psychiatrist says immigration authorities wanted details about the high rates of mental illness among children at the centres to be removed from his official reports.

He was asked to delete clinical opinions that made a direct link between prolonged detention and mental health problems.

Dr Young was director of International Health and Medical Services (IHMS) - a private health service contracted by Australia's Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP), external to provide health care to detention centres - a role he held for three years.

'Bad behaviour'

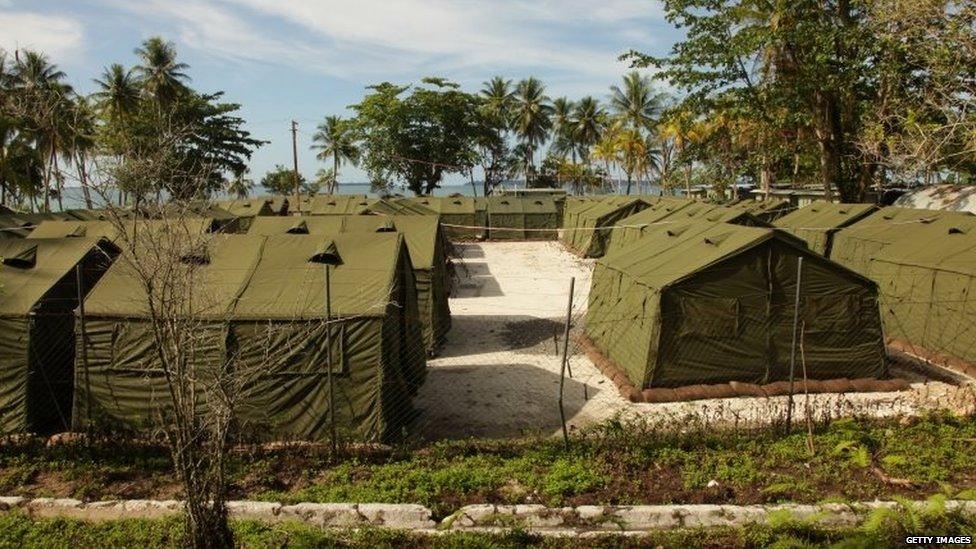

Its services covered the country's controversial offshore facilities on the Pacific island of Nauru and Papua New Guinea's Manus Island, where all asylum seekers who try to reach Australia by boat are sent - never to be resettled in Australia even if their refugee claims are proven.

In advising on treatment, Dr Young argued with authorities who considered acts of self-harm by detainees as "a type of bad behaviour, rather than a manifestation of people in extreme states of hopelessness".

Refugees burnt their Nauru detention centre housing in 2013

He says he was later refused permission to use data he had collected about health issues in detention centres in presentations or publications.

"They made it very clear this type of information should never get into the public domain," he told the BBC.

Now there is fear that health workers could go to prison for such revelations under new Border Force laws, external that threaten "entrusted people" with up to two years in prison if they reveal protected information about Australia's detention facilities.

In recent months, hundreds of doctors and nurses have staged public protests in cities across Australia, posing with their hands over their mouths to highlight the risk of being silenced.

Their concerns are shared by Australia's 13 peak medical groups, who have accused the government of trying to "gag" health professionals.

The World Medical Association has also warned the laws are "in striking conflict with basic principles of medical ethics".

Some Australians are unhappy with the offshore detention centre system

Critics say the gag is the latest act in a "culture of secrecy" around tough Australian policies designed to stop boatloads of asylum seekers from arriving on Australian shores.

The government is unapologetic about its stance on "stopping the boats"

It denies it is trying to silence doctors and nurses or that it wants to suppress health information.

The Border Force says the new laws are to protect "operational security" and insists robust internal mechanisms are in place through which medical concerns can be raised and addressed.

The federal Labor opposition agrees. It supported the legislation and says health workers will be protected by 'whistleblower' protections under the Commonwealth Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013, external.

However, legal experts say it is not clear what sort of information would be protected and there are a range of internal hurdles that could delay or deter disclosures.

'Chilling effect'

That confusion alone may suit the government, says human rights lawyer George Newhouse.

"I think the government is very happy with the uncertainty around the laws and how they are likely to have a 'chilling effect' on potential whistleblowers," he told the BBC.

Given very restricted public access to Australian detention centres, health and social workers have been key sources of information about conditions.

Two former medical officers at the Christmas Island detention facility, last year graphically catalogued a range of health concerns in an article in the Medical Journal of Australia, saying, among other things, that "degrading, harmful and inappropriate incidents" had occurred at the centre.

"Degrading, harmful and inappropriate incidents have occurred, including requiring asylum seekers to undergo health assessments while exhausted, dehydrated and filthy, with clothing soiled by urine and faeces; addressing individuals by number instead of name, artificial delays in transfer of patients for tertiary care; confiscation and destruction of medications, medical records and medical devices; and detention of children despite clear evidence of significant harm."

--Medical Journal of Australia, external, Volume 201, October 2014

Dr Young believes the risk of being sent to prison will discourage medical staff from speaking out in future, even if no prosecutions are launched.

Other detention centre practices like employing staff from developing countries who are not protected by Australian labour or whistleblower laws also "keep the lid on all information flowing out of the system", he says.

"My position is that the medical profession is expected to speak out when it comes to issues that harm people's health.

"There would be no controversy if I was speaking about cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure.

"The evidence is very clear that prolonged detention in such circumstances causes a negative health impact, and keeping those health impacts secret makes the situation worse."

Marie McInerney is a Melbourne-based writer.

- Published12 June 2015

- Published31 October 2017

- Published12 June 2015

- Published12 June 2015

- Published18 February 2015