Migrant crisis: How will Australia's Syrian refugee pledge work?

- Published

Tens of thousands of people have been crossing over into Europe from Africa and the Middle East in recent weeks

In a major policy turnaround, the Australian government has said it will significantly increase its refugee intake and its financial aid to the UN for people displaced by the conflicts in the Middle East.

The government also said it would extend its campaign of air strikes against the so-called Islamic State (IS) in Iraq into Syria.

So, how will Australia decide which refugees it will take, and what will happen to them when they arrive?

Who will be accepted?

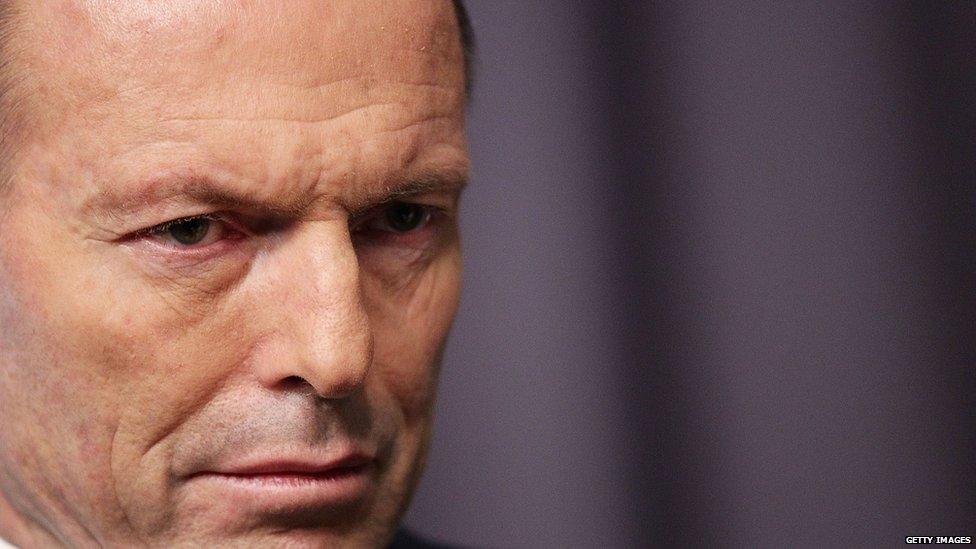

Prime Minister Tony Abbott said Australia would take in 12,000 Syrian refugees from persecuted minorities - a significant increase on the 13,750 refugee places Australia had set aside for 2015.

Mr Abbott has said the increased refugee intake is "generous"

A team of Australian government officials will soon depart for the Middle East to work with the UN's refugee agency to identify and process potential candidates for resettlement.

The government said its focus would be on those people most in need, in particular, the women, children and families of persecuted Syrian minorities who have sought refuge from the conflict in neighbouring Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey.

Australian officials told local media the first refugees - who must pass health and security tests - could be in the country by December and the full 12,000 people settled by mid-2016.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates there are 7.6 million internally displaced Syrians and an another 4 million who have fled in search of protection.

Which countries are in the best position to take migrants?

Where will they live?

In the biggest refugee resettlement in Australia in decades, it is likely the 12,000 Syrians will be resettled across Australia in major cities.

Sydney's Villawood detention centre holds visa overstayers and people who arrived in Australia without visas

Some regional towns have offered to take some of the refugees but they would need significant financial help to do so.

The refugees are not expected to be housed in existing detention centres, such as the one in Villawood, in western Sydney, because those facilities - already mostly operating at capacity - house people whose refugee status has yet to be determined.

Support such as English lessons, education for children and health services, will have to be provided, with the government estimating a total cost of up to A$700m ($494m; £321m) over four years.

How have people reacted?

The UNHCR "warmly" welcomed the announcement, as did many Australians, including some in Mr Abbott's own Liberal Party who had been urging him to take more refugees.

Australians have been calling on the government to do more to help refugees

Premier of Australia's most populous state, New South Wales, Mike Baird, whose recent plea to the government to do more is believed to have influenced Mr Abbott's decision, applauded "this bold and generous decision".

The Labor Opposition - which had called for an extra 10,000 refugee places and A$100m in extra aid - also welcomed the announcement but warned the government not to take

Greens leader Richard Di Natale tweeted that, external every refugee welcomed into Australia was "another person with a chance", but said bombing Syria "will only create more refugees and more suffering".

Why is Australia only taking refugees from 'persecuted minorities'?

In recent days, a number of prominent government members have said Australia should only accept Christian Syrians, sparking fierce criticism from other quarters.

Millions of Syrians have fled their homes to camps in neighbouring countries in search of safety

But Mr Abbott denied the government was discriminating against Muslim Syrians who also face grave peril.

"There are persecuted minorities that are Muslim, there are persecuted minorities that are non-Muslim and our focus is on the persecuted minorities who have been displaced and are very unlikely ever to be able to go back to their original homes," he told journalists at a press conference.

Is it legal to bomb Syria?

But Mr Abbott said the legal basis for the new operations came under "collective self-defence", because IS militants in Syria threatened both Iraq and the international community.

Australia has been bombing IS targets in Iraq since last year

Article 51 of the UN charter guarantees "the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a member of the United Nations".

But legal experts say such a defence is problematic because some international law cases have ruled it can only be relied upon in the defence of one state against another, and IS is not recognised in law as a state.

Australia's Air Task Group, deployed to the Middle East region, consists of six F/A-18 Hornet aircraft, a KC-30A Multi-Role Tanker Transport and an E-7A Wedgetail Airborne Early Warning and Control aircraft.

The government said its decision to extend Australia's air strikes against IS into Syria followed Iraq's requests for international assistance against IS strongholds, and a formal request from the US.